Ai Weiwei’s Hope in The Jaws Of The Monster

Written by Matthew Ponsford

01 OCT 2020: ‘I loved New York—every inch of it. It was like a monster.’

In the story Ai Weiwei tells, there’s always got to be a monster. In New York – where his new series of films for CIRCA 2020 begin, amid street protests that set in motion his journey toward human rights activism – the city convulses like a beast. He writes in his diary after interrogation by a Chinese prison guard that it is always a monster that draws the soldier to a fight, and without this foe, the soldier has no identity. And the monster, he explains, is what we’re fighting today.

And yet the story he tells, again and again, teeters with hope, with personal joy, and even with belief in miracles. The moral, as it begins to appear, seems to be: the monster is not simply the totalitarian, not simply a power stronger than all of us. But we can’t win until we know what the monster is made of.

03 OCT 2020: ‘My favorite word? It’s ‘act.’

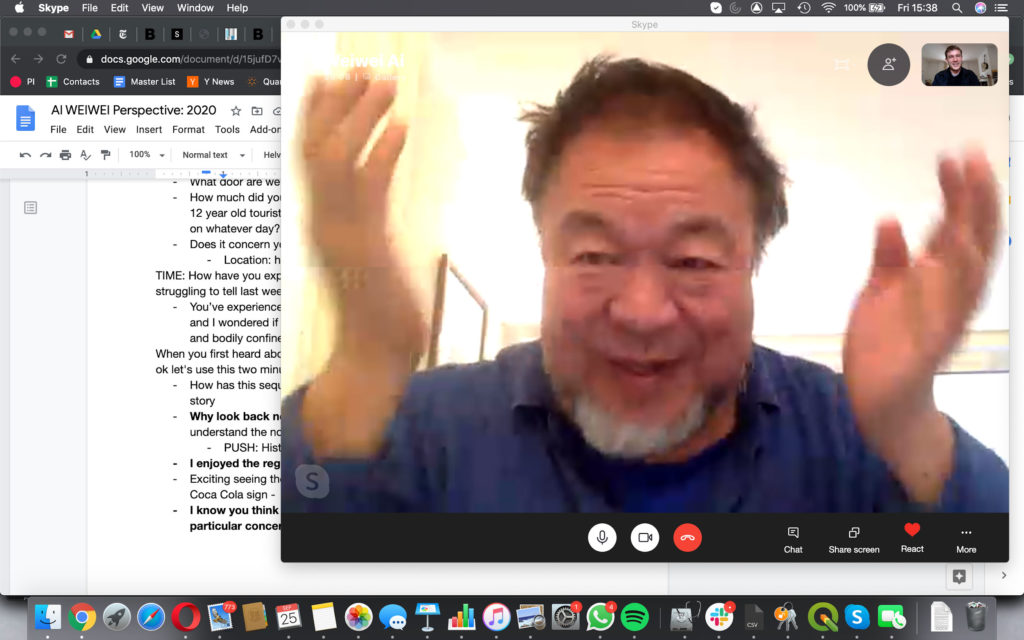

In October 2020, we are in a moment of profound loss, on an island of time cut off from the past and lacking any real conviction that a future is coming. Just as time during lockdown seems to slip, it also stalls, says Ai Weiwei on a computer screen, talking to me from his living room in Cambridge. He’s written an article about it for The Atlantic, drawing on his experience of being locked in a small cell for 81 days in solitary confinement. This is a moment many of us would rather forget – and we will, which is all the more dangerous. Ai searches for the right experience to compare it to, some kind of disaster, maybe, a “tsunami”:

“When it is over, it’s over”, says Ai. Our minds shut it off. We will put it in a box. “Or it’s even like a horror movie: when the lights [come] up, we go back to normal. So our memories or emotions are deleted or”… he describes something like compartmentalising something traumatic, a dark box we put memories into when they exist outside the continuous chain of cause and effect. When an event like this happens… “We put it somewhere which is ‘not-normal’.”

Totalitarians are fond of these moments, since they’re so easily vanished or rewritten like war stories that become rose-tinted in retelling: “Human society is like a tragic child,” summarises Ai, looking out at the screen. “Because you don’t know the past, you’re so uncertain about the future. That really creates a perfect condition of purposelessness. And that is a real challenge for a human state of mind.”

And yet, there’s such hope.

In 2020, as waves of protest have swept aside monuments to decrepit historical tyranny, purposelessness has not won. And following the toppling of statues to the architects of Western slavery and demonstrations against police violence across the UK and U.S., there is new relevance of Ai’s earliest works.

Photographs from his time in New York between 1983 and and 1993, document the ACT UP demonstrations against government inaction on the AIDS crisis, protests against racial and gender-based violence, and the Tompkins Square Park riot in 1988 [To be displayed on the CIRCA screen on 01 OCT 2020]. Ai’s black-and-white photos of the riot in Tompkins Square Park were used by the American Civil Liberties Union to prove that police had incited the riot by cracking down on demonstrators with extreme brutality. For Ai, in the years running up to Tiananmen Square, it was the eye-opening education in the potential of rights-based protest and the violence of Western democratic powers.

In Ai’s early work, such rebellion is not only a necessary step to break from ghost stories of tradition, but can in itself begin to construct a new, truer way of living that draws its force from the voices of the living. Both Study of Perspective and Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn series [both from 1995 and displayed on 02 and 03 OCT 2020] not only attacked the cultural value of monuments but agitated to replace memorialisation with practices of democratic intervention. Often misrepresented as futile gestures to power, or blunt criticisms of Maoism, Ai’s destruction of an urn had, 25 years ago, already provided one answer to all those who argued that the toppling of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston amounted to an erasure of history. “I don’t think the past can be so easily destroyed by taking down monuments,” says Ai on a rainy Friday at the end of September, as he prepares the final edits of the new films, revisiting such early works. “The real monuments should always be won. [By] people taking down a monument, very often, a new monument is established in their mind or heart. So, we always give a new identity to our time by reexamining the past. The past has already had a conclusion – the monument is that conclusion. And very often, [a new generation] realise they cannot accept it.”

Having questioned before lockdown whether he might move away from art, Ai, at present, he does not seem dulled in his multi-pronged creative output or his desire to leverage it for social change. Indeed the CIRCA films, although traversing history, point to a future made possible through committed action, repeatedly highlighting the centrality of the act of dissent, and the moment of revolt – from Perspective and Urn to the film Cockroach about the pro-democracy uprisings in Hong Kong [Footage from the forthcoming film appears 26 OCT 2020].

The thirty new films he has produced will be screened on the gigantic corner wall of Piccadilly Circus. Ai has been curious about his new “colonial” surroundings since moving to the UK almost exactly a year ago, recently unveiling an anti-war artwork in the atrium of the Imperial War Museum and chastising Britain on the BBC’s Today Programme for its unwillingness to engage meaningfully with its former colonial subjects in Hong Kong. On the 2nd and 3rd October, when his two works from 1995 appear on the outsize screens of Piccadilly Circus, they will shine a light out from just about the epicentre of British imperial pageantry, a few hundred yards from both the Houses of Parliament and Buckingham Palace, and into the the commercial heart of London.

The appeal to historical myth as a lazy foundation for value has been playfully mocked by Ai and, here too, he carefully endorses material change. Careful not to speak on the behalf of any protest but his own, he says it is clear that the establishment now denies the “new clear definition” of our time. “There’s conflict between our understanding and the establishment. And when those things happen, taking down the monument is only a small act.”

04 OCT 2020: ‘Freedom is a god-given right. No matter if you are rich or poor, intelligent or not, it belongs to you, and no one can touch it.’

On Piccadilly’s screen, Ai’s episodic films together form something like an hour long auto-biopic, taking us from his initiating experience of conceptual art, as a student in New York, to the Coronavirus crisis in which we are morassed, through the planetary environmental crises that have become a focus of his work.

Ai is excited about the “subversive” possibilities of escaping the museum to display in an unexpected corner of the city. The artist who has painted the Coca Cola logo on the side of ancient Chinese vases, as a symbol of the unbounded domination of consumer culture will, for two minutes each day, push aside the Coca Cola advertising sign that has lit up this monument since 1955, two years before his birth.

Ai recently turned 63 and calls CIRCA one of his major works – a chance to sift through his history, from his groundbreaking early series to recent films and installations, to find lessons for the challenges of today. “This project gave me a chance to rethink how I started my art, and my activism and my involvement with social change and human rights and freedom of speech.”

Initially created during eight years of intensive travel (1995-2003), the images for the Study of Perspective series have now been assembled over three decades, and juxtapose the minuscule individual against the massive architecture of power – Tiananmen Square, the Eiffel Tower, the White House or Trump Tower. “To put something in the public space is very challenging,” he says, explaining that he never imagined his middle finger appearing at a scale equal to the monuments he flips off. “Those are very private moments. You take a camera to shoot in your left hand, with one finger [stuck] out to those cultural institutions or political institutions. But it’s a private, harmless moment. Ironically, I would never imagine those images can be used in public and in an advertising entity, or on that kind of scale. So it re-examines and gives a very different meaning to this attitude.”

Although the first of Ai’s 30 films will take viewers back to the start of his career, the success of the new CIRCA commission has been in retraining a focus on the question of where we go from here. Unlike major museum exhibitions, which are commissioned years in advance, the entire process, from the first email to Ai’s studio, to it appearing on the screen has taken less than three months, allowing the artists to respond in public to issues that are still very much alive. Among them unseen footage from unreleased documentaries and not before seen images from historic series.

Ai’s 30-day CIRCA programme spotlights a body of work that prefigures more than just the battle for memory and memorials: railing against thousands of deaths caused by political negligence and the horrors of a brainless surveillance state; swimming in the murky timelines of lives spend in confinement, apparently both endless and vanishing; casting bodies as weapons and independent actors as the only real barrier we can build against totalitarianism.

Fresh context is clearest in the written messages that punctuate each film, most drawn from Ai’s journal (some of which have been pulled out as the dotted headers of this essay). I suggest to him that each seems to be a call to action: “Not necessarily,” he responds. “Even in the most painful and the most deadly situations, I’m still trying to seek irony, joy.”

05 OCT 2020: ‘If you seek to understand your motherland, you are already on the road to becoming a criminal.’

In his latest film, a two hour documentary named Coronation [27 OCT 2020], Ai documents life inside Wuhan, the birthplace of the pandemic, as regular people negotiate the all powerful military lockdown in interactions both tragic and absurd. “I really clearly examine how efficient authoritarian society functions,” says Ai, who orchestrated amateur cinematographers to capture haunting images of the city-turned-prison. “And, yes, they are very efficient, and not only because they can limit the openness of the discussion and the information.”

The Chinese government proved successful at quarantining the early, terrible news that threatened to burst out in the early days of the disease and then, later, rigorous in its efforts to stem the spread of the disease. “They can really lock down the city, lock down every individual in their household. They simply cannot physically come out, because the door is sealed and locked, and there is a guard on the street and they will put you in jail, immediately. So this kind of military style efficiently stopped the virus spreading.”

Liberal democracies’s failure to control the virus have been clear for all to see. The U.S. and UK, as well Brazil and India, have been among the world’s least effective, resulting in excess deaths on a massive scale. Since early March, there have been only rare days when China has reported more than 100 new cases, while the USA has recorded more than 20,000 new cases each day for the last two months. For Ai, this is the trade-off between rights and efficiency. “In the West – in the UK or the US or in many other nations – the disease, the government cannot really make clear decisions on how humans should behave,” he says. “So very often the argument says the democratic government doesn’t have the same kind of efficiency as authoritarian society towards some massive, unified decisions, which is true.”

But Ai resists any call for expediency to temper democracy. His films [26 OCT 2020] highlight the crackdown on pro-democracy uprising in Hong Kong in 2019 and remind of the arbitrary suffering inflicted on him – imprisonment, deprivation, torture of solitary confinement, a cerebral haemorrhage following a police beating – while pointing to the far greater unheard victims of repression and state violence [18 OCT 2020]. Ai takes a long view of the crisis, considering the decades of brutality that have preceded it, and answers that the authoritarian political system means that life in China has “no meaning”.

“The cost of China is, you will never have individual intelligence and imagination and passion,” he says. “Yes, [democracies] may make mistakes, but we are able to control our own fate… every step of a decision has to respect the rights of the individual and human rights. So, that’s the big difference.”

08 OCT 2020: ‘It takes an enemy to make me a soldier. If I don’t have a great monster to fight, who am I?’

Ai Weiwei was born 28 August 1957 in Beijing. His father Ai Qing was among the most famous poets in 20th Century China, influenced by early Soviet writers including Mayakovsky and modern Western poets including Walt Whitman, in addition to his own experiences being brought up in a peasant household, amid the pre-revolutionary environment of 1930s east China. The family name Ai 艾 was invented by Ai Qing, during the older Ai’s time in jail, by striking a cross through the lower part of the family name he had inherited at birth, Jiang 蒋. In an interview with the journal China Heritage in 2018, Ai explains that his father gave him his name pointing into a dictionary with his eyes closed, hitting the character Wei 未. Wei can bear the meanings “future” or “not yet” but its meaning when the character doubled is unclear. Ai says he is glad to have a unique name but doesn’t dwell on the meaning.

Ai Qing was at one time close to Mao Zedong, but was denounced by peers as counter-revolutionary after defending a fellow writer, around the time of his son’s birth. The family were exiled in 1958 to Heilongjiang, in northeastern China, and then to Xinjiang on the country’s eastern edge, where they lived for 16 years. “I started just like anybody else,” explains Ai. I take this to mean without a privileged upbringing. “My father was exiled, I never really had a good formal education. And we always have been seen as dissidents. That means your situation is always put in danger, because they say you’re against the party, against the country.”

Ai’s lifelong personal battles with the Chinese government are well documented, including a four years or imprisonment and house arrest between 2011 and 2015, in which he was subjected to interrogations, charged with tax evasion, and banned from leaving the country. The question asked above – “If I don’t have a great monster to fight, who am I?” – Ai says he asked an interrogator during this period of repression and appears at the end of a film [08 OCT 2020] that records the demolition of his Shanghai studio by the Chinese authorities in 2011. His subsequent studio was bulldozed as well, this time without warning, in 2018.

But Ai says that in the four decades since he first left China, the struggle against totalitarianism has become less contained within national borders. In an article published in the New York Times just before lockdown, he criticised European and American manufacturers, including Volkswagen, Unilever and Nestlé, for producing goods in Xinjiang, where as many as a million ethnic Uighurs and other prisoners have been kept in internment camps. Many of his targets were based in Germany (where Ai lived between 2015-2019, before moving to Cambridge). He accuses those producers of cynically exploiting vague ideas of “cultural difference” to excuse themselves from their human rights obligations – all while Western diplomacy, big business, and Chinese authoritarianism have been active partners in Xinjiang’s brutal regime of hyper-surveillance and cheap labour.

“Since I started, very early around the early 90s, I started really thinking about what would be the struggle after the Cold War, after the Berlin Wall comes down,” says Ai. “So I started to realise the ultimate struggle will be individuals, under the power of the collective essence of political power.” He name-checks Muji, Uniqlo, H & M, and Adidas – all retailers with flagship stores in the shopping district that ring the Picadilly Circus screen – whose supply chains are linked through Xinjiang’s vast, sparsely populated desert terrain. “The real financial and political power today has no border and no religion and not any kind of restrictions. They are moving to become much faster, bigger and much more profitable than human society can ever imagine. And individual rights and human rights have been facing a real challenge – and a new challenge.”

11 OCT 2020: ‘Freedom is not an absolute condition, but a result of resistance.’

There is no naive triumphalism in Ai’s rebellion – no imagined moment where the political power of the Chinese Communist Party or global financial order falls to individual rebellion. “I’m a failure, anyway,” he says during a plaintive moment during our discussion. “Because how can you confront this authoritarian, powerful state like China? It’s impossible, it’s been proved by my father’s generation – millions of intellectuals, vanished.”

Ai’s fifth film [05 OCT 2020] will show a roll-call of 5,219 names of children who were killed in the Sichuan earthquake, when flimsy “tofu-skin schools” built in corrupt deals between government officials and construction companies, buckled. These names were not collected by any official source, but by a citizen’s investigation launched by Ai in 2008, to counter an official omerta. This attempt to hold to account the system triggered among the most brutal periods of repression of Ai’s work by the Chinese state, including his imprisonment in solitary confinement, which he describes as a form of mental torture. The earthquake’s brutal fallout is one case-study for Ai’s fear that regimes can sponsor memory erasure. By spending a year documenting it, his team (mostly assembled from young volunteers) provide an example for how resistance is possible.

I ask if he has seen the recent New York Times front page, when the death toll from COVID-19 hit 100,000 in the US. It listed the names and told stories about hundreds who had died, in a journalistic attempt to humanise the victims of the virus, and preserve a memory of lives extinguished by official negligence. For Ai, the Sichuan disaster was a crushing experience, the emotional weight of political failure, which compelled him to take actions that he is still paying for. (He is desperate to see his ageing mother, Gao Ying, but visiting her in China carries risks.)

Could these moments be similarly inciting for many in the U.S. – where the death count has already hit 200,000, and the deaths of 500 or 1,000 in a day might no longer make the front page – or here in the UK, as infection rates again spike, I ask? “I think every day, our humanity is – I don’t know how to say it in English – at such a challenge,” he responds. Seeing what is going on around us and not knowing how to do anything is stultifying: “It’s like looking at a bleeding wound, and being incapable of stopping the bleeding and healing it. But on our human body, it’s not just one location but several locations with those open wounds.”

13 OCT 2020: ‘Body as weapon’

Ai’s diagnosis of the way to begin resisting and the way to begin healing these wounds are one in the same. “I think that the only thing we need concern is to make a better ourself, rather than better world,” he concludes.

Ai’s position far from ego-centrism. The tension between collectivity and individuality has always been central to Ai’s work, not least his giant Sunflower Seeds commission for Turbine Hall [09 OCT 2020], in which made up of millions of hand painted porcelain seeds, each seemingly identical, yet unique. He believes that communal struggle for a better world requires us to rid ourselves of “selfish” instincts and take responsibility for human and non-human life: “Individuals never really prepared to accept this kind of challenge,” he says, discussing the new complex of global financial and political actors. “So, first, it really takes our consciousness, and our understanding about what life is about and how an individual can be involved, and can contribute to the social struggle.”

Individual acts contribute to this sense of a better “ourself”. Here, Ai can again demonstrate what he preaches, facing violent retribution for defending fellow artists and activists, including advocate Tan Zuoren, whose trial Ai was attending as a witness when he was detained and beaten. Like his father, Ai has taken this responsibility despite the cost. “Also to establish this belief: this is possible,” he adds. “It is possible by individual acts and the individual intelligence, emotions, and the sensitivity to really overcome this – this monster-like totalitarianism.”

Many of Ai’s works can be seen as an attempt to bridge this gap, with images and experiences – spoken with humour or pathos – that can be understood by an audience outside of the museum. They don’t necessarily usher viewers from purposelessness to all the way to action, but lead toward some form of agency.

Ai’s monsters encompass not only political evil and corporate control, but increasingly the destruction of the natural and animal life, as well as refugee crises driven by war, political violence, environmental collapse, and famine. Omni, his first virtual reality video, paired human and animal concerns, entwines the stories of Rohingya refugees [20 OCT 2020] in Bangladesh’s gigantic Cox’s Bazar camp with the fate of working elephants once employed in the Burmese logging industry. His latest new museum work, History of Bombs [Little Boy, 29 OCT 2020], is at London’s Imperial War Museum until May 2021, where he has taken over the floor of the museum to explore the deathly power of different explosives designed to kill ever-more clinically or indiscriminately. In an institution which typically lionises warriors and invites us to gaze admiringly at war machines, Ai’s addition tilts the balance toward discomfort and, frankly, disgust.

In an interview with The Guardian earlier this year, Ai ended by talking about his waning energy to go on creating art, suggesting he might open a hair salon. But there is little of that apparent now, even as he complains he looks tired in his webcam reflection. In CIRCA, surveying what he has made, it is creative acts of resistance that begin this process of cultivating empathetic agency in public, even in a landscape of totalitarian repression or indifference. “Art is so powerful in those moments, because it’s so detached and no authoritarian can stop you doing art. That language, they don’t understand. They just simply don’t understand what gave you such a privilege to do that. So, most of my acts, if I look through those 30 pieces, maybe even more than half of them is just my personal joy.”

All this focus on oneself is because, he says, the essence of what we’re fighting is not external to us, as individuals or as a species. “It has become some kind of mythology. It’s like: we are fighting. And we are struggling. But who is the enemy? You know: what are we really fighting, as human society?”

“I think the real monster is ourself,” he shrugs. “There’s no other monsters. The universe is at peace, at a harmonious stage, without human society.”

“Humans create as their own enemy. They build the bombs. They are trying to master nature. And then, of course, they are very greedy, selfish, and they’re insecure, and they’re not intelligent.”

26 OCT 2020: ‘Freedom only comes from struggle, liberty is about the fight.’

I ask Ai: in planning for CIRCA 2020, how much did you think about the pedestrian walking through Piccadilly Circus – the London businessman, the teenage tourist, the Westminster City Council staff member – who happens to find themselves under the advertisers’ lights at 8:20 that day? “The art has been put there to give a surprise. And it’s almost surreal,” he says, to offer up images stripped of the advertiser’s rationale to sell or seduce you with the product.

Ai is less concerned with the audiences who might already have sought his work out in galleries than he is with these unexpectant passers-by. Making a change to their mindsets, even connecting with them, is not guaranteed. But to not try would be to demonstrate the failure of imagination and purpose.

Ai has spent a lot of time during lockdown with his 10-year-old son, Ai Lao, who appears almost every day on his Instagram, picking mushrooms, climbing hay bales, giving his dad a haircut. His education has driven his decision to move to England, after experiencing hostility in Berlin.

During our conversation, “responsibility” – a word he repeatedly uses – seems to be what is driving Ai today. Why his works are increasingly skewing toward mass media documentaries and film and the public realm: the opportunities he has been given to attempt to communicate are not ones he can refuse.

“You always believe there’s a possibility. You always believe there’s a miracle,” he says, speaking of breaking through to new audiences. “I always call for humanity. I always think there’s good will for the next generation. Of course, I believe they also have to fight but we have to solve the issues right in front of us should not give those issues to the next generation.”

This process of purging selfishness, rediscovering responsibility, is what ultimately means we can look in the mirror and not see a worthy animal, and not a monster in ourselves, he explains.

“With no compassion, we’re just selfish creatures. And if you’re just a selfish creature, anything that happens to you is, right, you know? The only thing you can blame is yourself .”

“We have to come back to ourselves, to bring back our memory. That means we have to re-establish our ability to care. In a religious sense, we have to have compassion.”

29 OCT 2020: ‘Humans do not rule the universe. We are temporary passengers.’