Ai Weiwei: Investigating the Human Cost of the Refugee Crisis

Written by Charlie Colville

As we enter the last quarter of 2020, a new platform for the creation and exhibition of digital art was launched in the heart of Piccadilly Circus. Known as CIRCA, the platform allows for artists to showcase their work and ideas in the form of a two-minute video on the Piccadilly Lights, one of London’s most famous landmarks.

CIRCA have recently launched a collaborative project titled c. 20:20, which sees an artist take over the Piccadilly Lights for an entire month. This month will see the artist and activist Ai Weiwei deliver a series of videos documenting his career. On each day of October at 20:20 a video produced by Ai’s studio will be shown to the public both in Piccadilly Circus and online. The project combines video footage, photography, music, poetry, and art to present a colourful retrospective of Ai’s artistic career. Beginning with Ai’s early days in New York and culminating in his most recent projects, the series promises a deeper insight into his art, life, and relationship with the Chinese government.

With CIRCA’s collaboration with Ai Weiwei now nearing the end, the videos shown in Piccadilly Circus have become more reflective of current issues and events. In recent years, Ai’s work has presented an increasing concern for global issues that have affected multiple communities, with a particular focus on the Refugee Crisis and its handling. Many of the documentaries Ai has produced in the last five years have investigated the narratives of refugees in relation to what is portrayed in media, choosing instead to appeal to human emotion and sympathies. As a displaced person himself, Ai has been able to emphasise the impact of this experience on a person and how traumatic it can be. As such, these are key themes for the videos released between the 18th and 22nd of October.

The Refugee Crisis

At this point it feels like the Refugee Crisis has been part of mainstream media for a very long time. In 2014, there was a spike in the number of people seeking sanctuary in other countries, with the total number of refugees reaching almost 60 million by the end of that year. This was the highest number of displaced people in the world since World War Two. Many of these refugees came from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Deaths are common amongst those seeking asylum in other countries, and in 2015 the number of deaths at sea rose to record levels. In April, five boats carrying around 2000 migrants to Europe sank in the Mediterranean Sea. The death toll was estimated at over 1200. One of the most well-recognised deaths in 2015 was that of Alan Kurdi, a 3-year-old Syrian boy whose drowned body washed up on a beach in Turkey. The photograph of Kurdi’s photograph is one of the most famous in characterising the human consequences surrounding the travel of asylum seekers.

The response to the Refugee Crisis in the UK has been characterised as chaotic and hostile. During the EU Referendum, a key motive for the LEAVE campaign was the implementation of better border control and a stricter immigration system. With Britain leaving the EU officially on the 31st January this year, the message could not come clearer that an anti-immigration movement is still going strong.

The Refugee Crisis is an issue that still persists today. In August of this year, UK media began reporting a quickly expanding predicament of people attempting to cross the Channel in small boats.

As mentioned, Ai can be considered an asylum seeker himself. After getting his passport back from the Chinese authorities in 2015, the artist resettled in Germany. Spending time in one of the most sought-after destination points for asylum seekers, Ai soon became involved in documenting the issues faced by refugees.

The following videos highlight how the Refugee Crisis has impacted us on a global scale in recent years, using the opportunity to highlight human tragedy and encourage sympathy. AT SEA is comprised of footage showing the arrival of refugees into Greece, which was later used by the artist in ‘Human Flow’, a documentary addressing the Refugee Crisis. ODYSSEY builds upon the human consequences and tragedy surrounding the journey of many refugees, combining the poster series ‘Good Neighbours’ and the portrait series ‘Banners’ from Ai’s public art exhibition ‘Good Fences Make Good Neighbours’. LAW OF THE JOURNEY concludes this section of Ai’s video series with an animated artwork from 2016. The images correspond to those seen in ‘Human Flow’, providing a visual statement on the way refugees are seen and treated.

AT SEA acts as the introductory video to this section of the series, establishing a focus on the refugee crisis and how it has been perceived through multiple points of view. The footage shows refugees being received in Greece, as their boats reach the shore. This section is comprised of multiple views of these boats approaching the shore, from shaky telescope images to distant aerial views. This play on perspective forms the bulk of footage and creates a visual metaphor for how the Refugee Crisis itself is perceived, as both something detached from main society (and therefore not a direct issue for us to solve) yet still considered too close for comfort. The alternation of long and short distances, which take place from the shore and the sea respectively, may also highlight the “them and us” divide that dominates the argument over the Refugee Crisis in many European countries.

Nevertheless, the latter part of the video emphasises the human presence behind the issue through footage of graves and the building of refugee camps. The latter of these is emphasised by the building of walls and borders, with footage taken from the point of view of someone looking into the camps. Again, perspective is utilised by Ai to highlight both sides of an issue, but the artist builds upon this idea through an emphasis of human interaction- we can see how people live in these camps, and it’s not scary or unfamiliar. As the artist states at the end of the video, “The border is not in Lesbos, it is in our minds and in our hearts.” As such, Ai provides a commentary on how the Refugee Crisis is not considered from a human perspective, but rather from social and economic prejudices.

ODYSSEY builds on Ai’s commentary on the Refugee Crisis through a combination of two artworks: ‘Banners’ and ‘Good Neighbours’. ‘Banners’ starts and ends the video with a selection of portraits of both contemporary and historical refugees. What makes the opening distinct, however, is that the portraits at the beginning of the video focus only on the eyes of each person. As such, the viewer is forced to make eye contact and establish a brief relationship with each person. This sense of creating a human connection becomes central to the video.

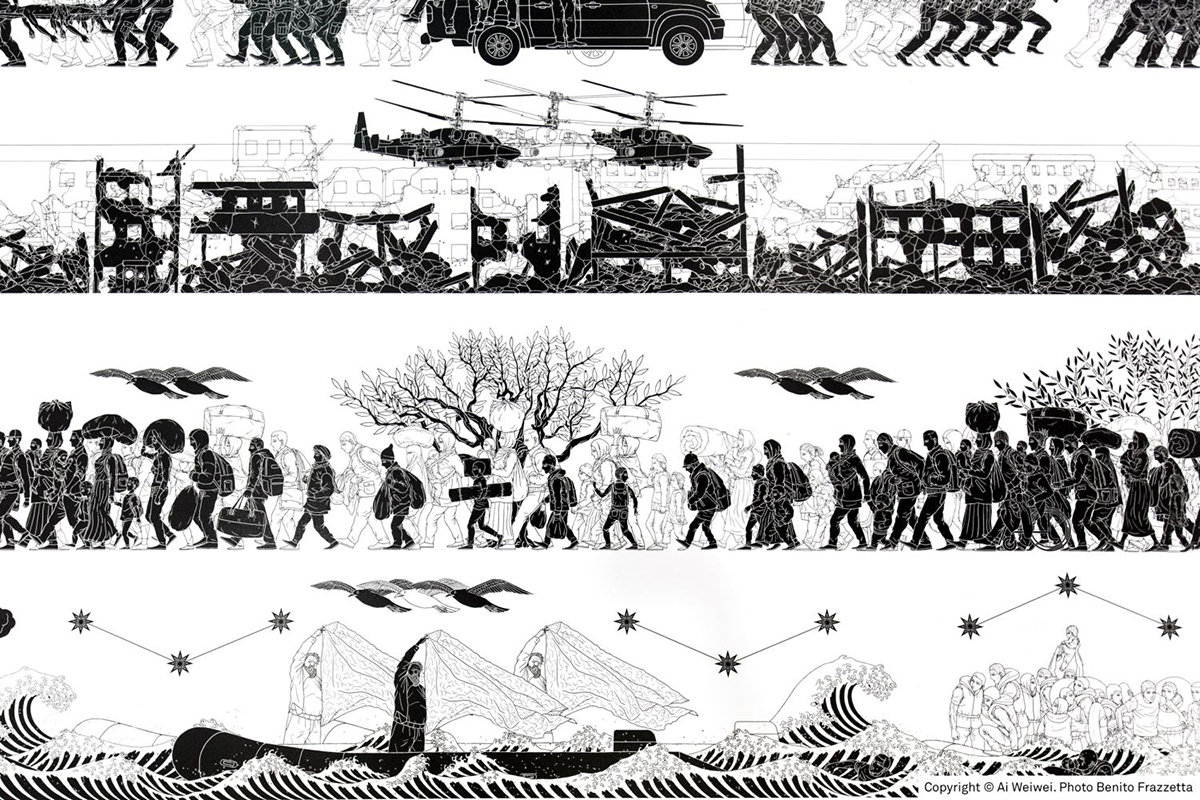

These portraits fade out into an animated version of Ai’s poster series, ‘Good Neighbours’, which depicts a silhouetted narrative of the Refugee Crisis. From the initial troubles in the refugees’ home countries, to fleeing, to coming across the ocean to Europe, the video visualises many refugees’ experiences as vulnerable people who have become victims of unfortunate circumstances.

More shots from ‘Banners’ end the video, but this time they show the full face of each person captured in a portrait. Again, we are encouraged to connect with each person, as the story put to these people pushes the viewer to acknowledge that actual people went through these events to get to where they are today. It highlights the idea that a refugee is a person, rather than a concept.

The video ends with Ai’s commentary: “The refugee crisis is a human crisis.” Once again, the artist makes an appeal to human emotion and sympathy, encouraging the viewer to connect with the people shown rather than the idea of a refugee. It also provides another layer of discourse to the issue, more specifically how labels are used to disconnect our judgement from our sense of collective humanity.

LAW OF THE JOURNEY rounds off the series with another animated version of one of Ai’s previous artworks (also titled ‘Law of the Journey’). The video depicts rubber people in rubber boats undertaking the journey of refugees at sea. With the emphasis of rubber, the animated artwork emphasises how people often see the boat first rather than the people inside- the image of the refugee is one that has been superseded by the fear of the boat invading our space. The rubber removes any distinct anthropomorphic quality so that all that is left is the vague outline of each person, leaving very little for viewers to connect with emotionally and on a human scale. Again, this is largely reflective of the way these people are portrayed in media outlets; not quite human, but rather objects of fascination.

However, Ai uses this to continue his appeal to the viewer’s human sentiment. At the video’s climax, hundreds of bodies are shown falling into the water and drowning, but the main figure is a young child shown face down. This figure is a striking resemblance to Alan Kurdi, which further emphasises the shock factor and human consequence of the Refugee Crisis. Despite how they are perceived as ‘other’, the fact is that they are vulnerable people willing to risk their lives for a better start somewhere else.

There are numerous theatrical characteristics in this video, arguably more than any of the others shown so far by Ai. From the operatic soundtrack and spotlights to the emphasis of a tragic narrative, the artist highlights how this situation has become a show for us to observe. As such, it criticises our role as the viewer – by not doing anything, we have become complicit in the tragedy depicted.

These videos showcase recent and recognisable circumstances which impact refugees on a global scale. Compared to his previous videos, Ai engages with the public in a way that is more confrontational- exposing viewers to the realities and human consequences that they otherwise may not see. With UK attitudes to the Refugee Crisis arguably more on the side of sceptical and hostile, Ai’s videos are an attempt to present a more human-centric appeal for the British public’s support.

We’re now approaching the end of October, and the end of Ai’s collaboration with CIRCA. With only a handful of videos left, I’m excited to see how Ai brings more of his work into the present and focuses on his more recent experiences.

Charlie Colville is the current Arts Editor for Mouthing Off magazine, an online platform designed to give young people the opportunity to find a new voice – a guttural scream loud enough to arouse fresh ideas, creative thought, and inspire artistic flair.