Eddie Peake: Reconsidering Relationships

Written by Charlie Colville

Are the relationships we see on our screens real? Or a manipulated fantasy?

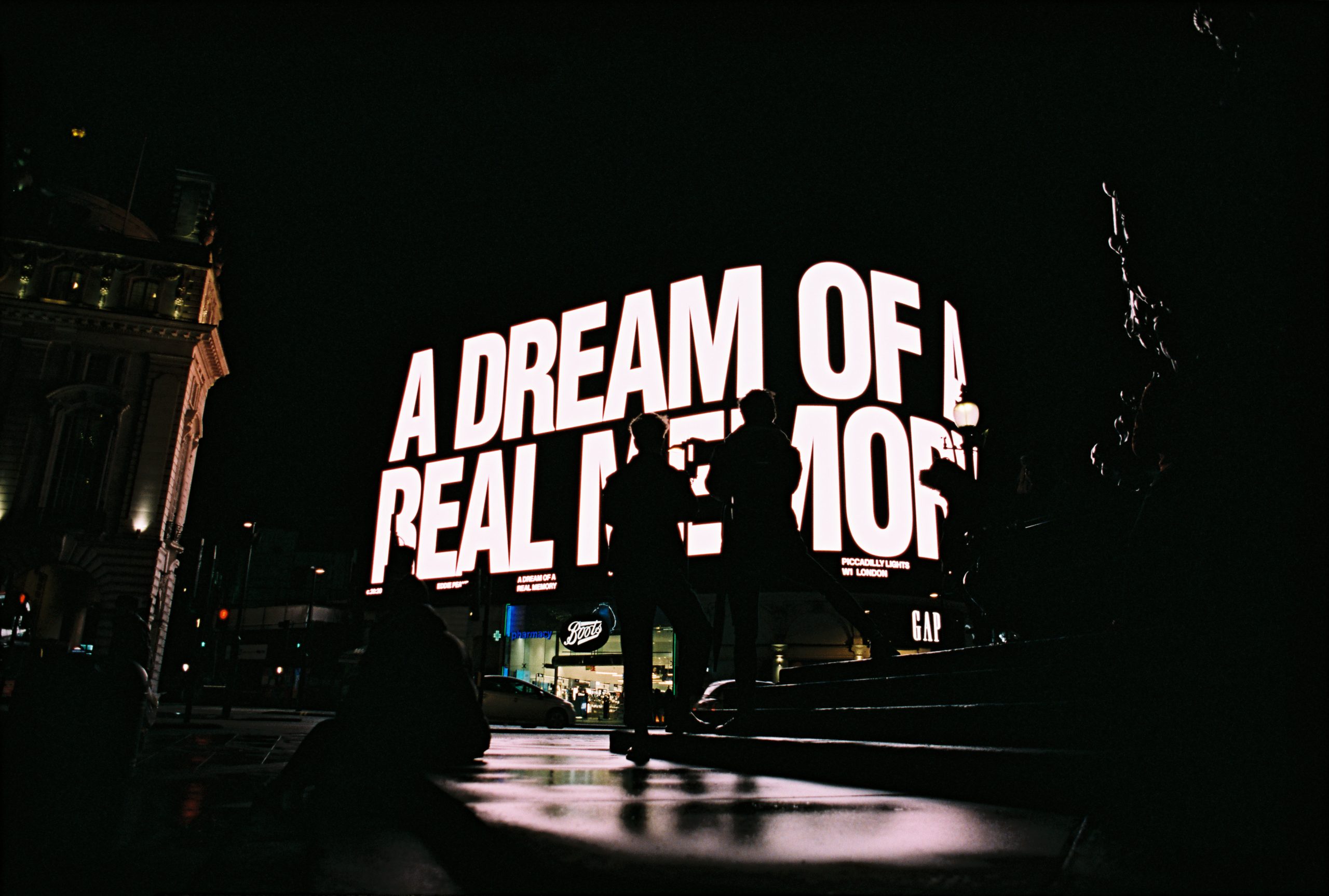

With galleries and museums shut for the majority of the past year, art has had to find a home in the less conventional spaces of the public domain. CIRCA, a new platform for the creation and exhibition of digital art, responded with a solution to the lack of art available for public viewing. CIRCA allows for artists to showcase their work and ideas in the form of a two-minute video on the Piccadilly Lights, one of London’s most famous landmarks. Each video is shown at 20:20 every night, breaking the usual stream of commercials and advertisements and creating a live exhibition experience. For those unable to make it to London, each video is streamed and archived on CIRCA’s website.

Each month has seen a different artist take to the big screen, sharing their work with the public through direct and disruptive means. December is no different, but unlike previous months this one is dedicated to an artist a little closer to home: British multidisciplinary artist Eddie Peake.

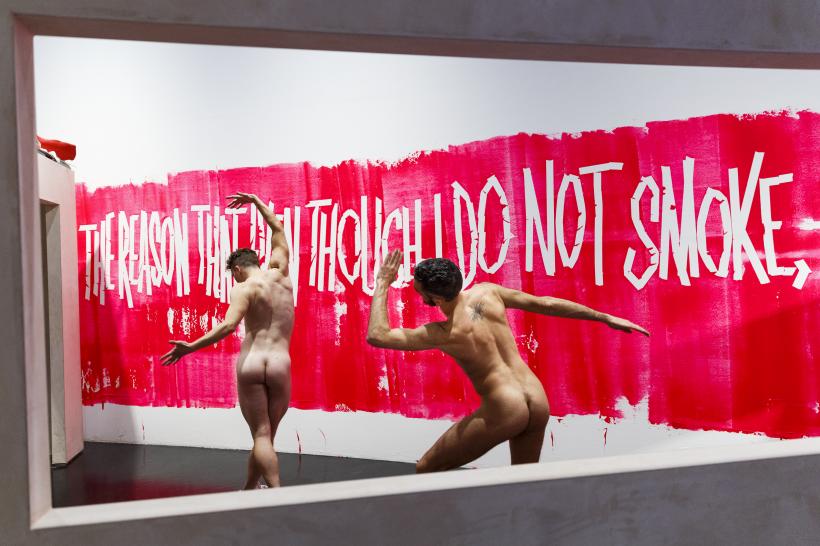

Eddie Peake is a London-based artist who works in a variety of media, including (but not limited to) performance, video, photography, painting, sculpture, and installation. Regardless of its appearance, the primary focus of Peake’s work is how forms of communication can be conveyed non-verbally between the lines of interaction between people, as well as artists, performers, and audiences.

Peake’s work often creates an immersive – and sometimes shocking – experience for the general public to observe and interact with. A facet of this work that draws the attention of passers-by is its exploration of the concept of relationships and how outer stimuli can impact them for the better or worse.

A Dream of A Real Memory

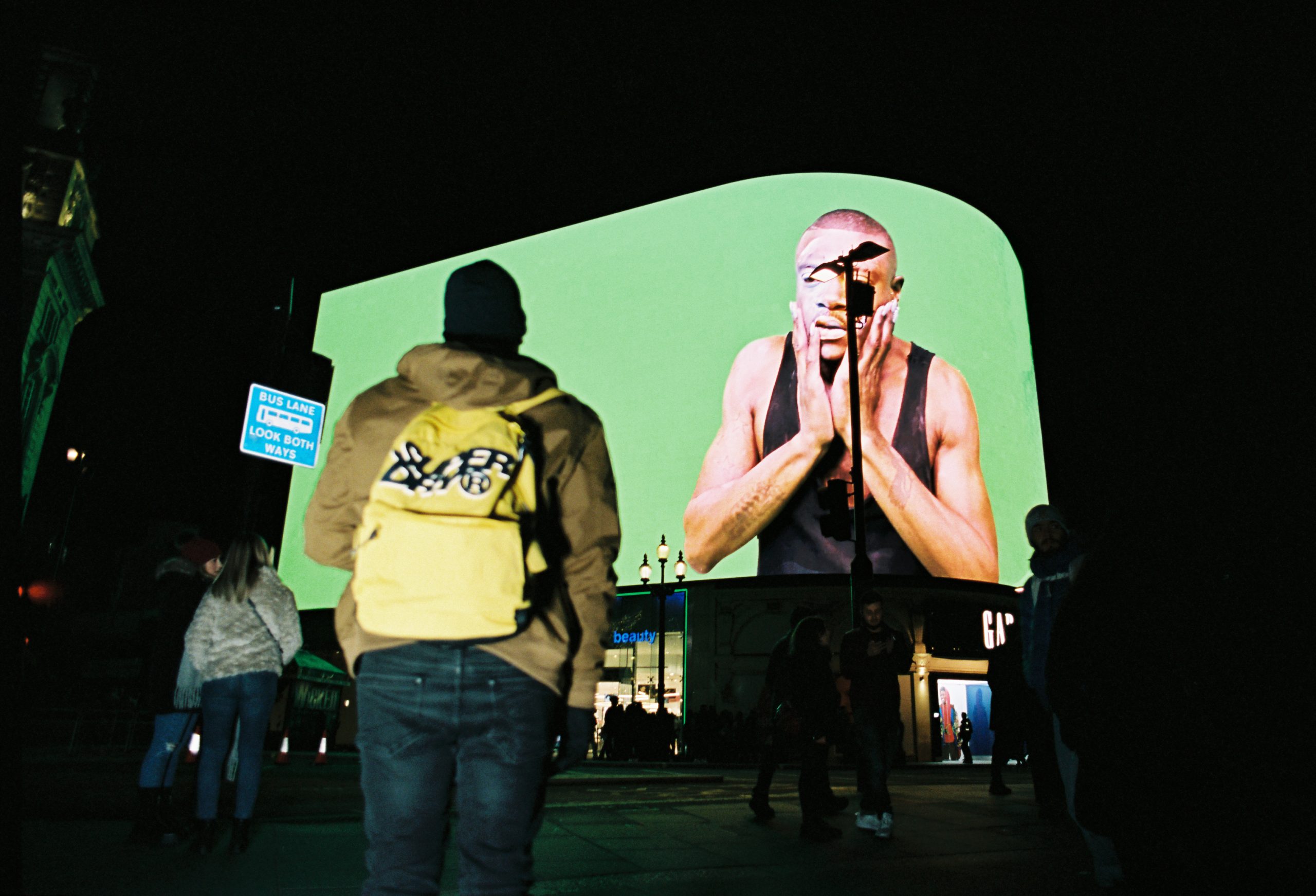

Eddie Peake’s contribution to CIRCA is ‘A Dream of A Real Memory’, a film which will be divided into thirty-one two-minute episodes for the Piccadilly Lights. The subject of the video is a group of three characters set within a green screen cyclorama: two dancers who form the majority of screen time, and the director or filmmaker (who is played by Peake).

The film is shown in reverse, playing from “the end” of the performance to “the beginning”. In doing so, viewers can see a backwards transition in the appearance of the characters onscreen, whose sweat-smudged makeup and straining limbs become gradually more pristine and stronger. The film’s audio is also played in reverse, warping each character’s speech and eliminating our ability to engage verbally with the narrative. By showing the film backwards, Peake tries to encapsulate the disjointed sensation that can be found in dreams and memories, which often warp and misrepresent true reality.

Relationships

As indicated by Eddie Peake on CIRCA’s website, ‘A Dream of A Real Memory’ examines how the progression (and degression) of relationships are impacted by outer stimuli.

As with Peake’s other works, the absence of verbal communication encourages viewers to analyse the dialogue present through physical movement and interaction. It’s therefore up to the viewer to fill in the gaps of the narrative that Peake presents them with; especially the relationships between characters, what they mean to each other, and how their interactions can be perceived.

The videos themselves facilitate multiple conceptual relationships between the characters onscreen, which the audience are able to engage with and follow as the film progresses throughout the month.

Two dancers form the bulk of content in each video, and their relationship can easily be read in romantic terms. The oscillating movements of the dancers create a language in which their interactions – every touch, repeated movement, and mirrored gesture – create the illusion of intimacy.

Episode 7, for example, spends the last quarter of the video showing the dancers tightly embracing each other, with their physical closeness being used to heighten the impression of emotional intimacy. The physical transition of these characters from softly cupping each other’s faces, to embracing, to holding each other translates into a visual language based on movement, conveying a relationship in which the characters cherish and depend on each for emotional substance. Later videos like Episode 17 reinforce this image, depicting the two characters curled into each other on the floor and using their close proximity as a point of focus for viewers.

Even the more aggressive movements of the characters (see Episode 8 and Episode 12 for examples) can be seen in relation to romantic relationships, conveying the anxieties, insecurities, and issues that are to be overcome when nurturing a relationship between two people. However, these moments of aggression and force are counterbalanced by more intimate scenes and gestures. The scene in Episode 8, where these two characters are shown cupping each other’s faces and smearing paint on each other, echoes this sentiment – with the movements mimicking both comforting caresses and wiping away tears.

By fixating on these small gestures, the viewer is able to pick up hints on the nature of the relationships presented in Peake’s film, and it becomes clear that body language is crucial in convincing the audience that these two characters are lovers.

Breaking the Fourth Wall

This relationship, however, is pulled into question by the appearance of a third character, the filmmaker. Not seen until Episode 9, the appearance of the filmmaker disrupts the bubble created by the two dancers. Breaking the illusion of a potentially intimate love story, his presence re-emphasises the fact that what is witnessing is a performance. Peake’s character brings the audience’s attention back to the superficial quality of the scene, which is visually marked by his camera (whose screen we can also see), the contained performance space, and the green screen. With the filmmaker now onscreen, the reality of the relationship we’ve seen between the dancers comes into question. How can we be sure of what is real and what is staged?

Viewing the film in its entirety reveals the reality of the constructed relationship we have been watching and investing our interest in; what was once perceived as romantic intimacy has now transitioned into a more complex reality that is based on a staged and work-based relationship. It finally hits home that these are acted scenes.

By breaking down our initial ideas and interpretations of the people represented onscreen, Peake presents a commentary on the “deceptive boundaries which dreams, memories, and reality possess” and the unattainable ideals found in capitalist marketing content. This latter point is emphasised by the presence of the greenscreen in the video, which has been described as “the fourth character” in the film.

While u sually an unseen tool in filming for TV, film, and advertising, the greenscreen fulfils a more visible role in Peake’s film. The greenscreen, in its more typical function, could again refer to the use of open, blank space for viewers to ‘fill in the gaps’ of meaning behind the interactions of the other characters. However, as previously mentioned, it also highlights the staged quality of the scene in a more literal and commercially produced sense. Peake reinforces the fact that this is a space for acting, and so the relationships we see onscreen are no longer concrete in their believability.

Capitalist Intervention

Following this vein of interpretation, capitalist institutions – in particular, the role of advertising – become a poignant reference for discourse in Peake’s videos.

The work employs the specific characteristics of the Piccadilly screen to create a narrative work that also criticises (laterally, not explicitly) the manipulative means by which capitalist machinery such as advertising entwines itself within our lives, deliberately playing on our desires, our anxieties and so on. – Eddie Peake

With this in mind, ‘A Dream of A Real Memory’ can be seen to examine the relationships people share with commercial society. As Peake notes, the role of our appearance on public platforms has become intertwined with all aspects of daily life, “deliberately playing on our desire, our anxieties.”

With commercial content played on a continuous loop on our screens – on TV, billboards, our tablets and phones – the public is constantly exposed to ideal versions of things we have in everyday life. We want these ideals, and if we do not have them, then we are conditioned to resent them. Manifesting into the various anxieties, we face on a daily basis – “Am I successful? Do I fit into this beauty convention? Will this make me desirable?” – Peake highlights how the reference template provided by commercial media content acts as another outer stimulus that can make or break a relationship.

It’s with these ideas that Peake’s videos play on the blurred boundaries between dreams, memories, and reality. What we see onscreen initially encourages viewers to invest emotionally in the characters and their relationships, but when this personal bubble is expanded by the introduction of new characters – outsiders – this reality is broken. Fourth walls are broken by first the filmmaker who watches the dancers, and then the realisation that we are also implicated in the narrative of watching something constructed.

How can we trust what we see when we know it is no longer genuine?

Real Life?

‘A Dream of A Real Memory’ acts as an extension of Peake’s regular practice of introducing live performances to the public through various visual media but also references his performance-to-camera artworks. As such, the film echoes Peake’s practice and working relationships in real life.

The dancers in ‘A Dream of A Real Memory’, Kieran Corrin Mitchell and Emma Fisher, have worked with Peake on his projects for several years, including ‘The Forever Loop’ (2015) and ‘Corpsing’ (2017). The breaks in the videos where the dancers are seen conversing with the filmmaker both on and off camera is ironically one of the more genuine interactions viewers will see onscreen, as it references the way in which Peake and his team work together to build the artist’s vision into actuality. This working relationship, based on Peake’s own reality, is something that rings true despite the conceptual set-up of the scene and broadens the scope of relationships within the artwork.

Something Missing

In ‘A Dream of A Real Memory’, both physical and conceptual boundaries are broken to make the viewer reconsider the social dynamics that are presented onscreen. This, in turn, encourages viewers to question the relationships prevalent in their own lives.

The physical contact between the characters we see onscreen forms scenes that are familiar to viewers but also distant in light of the social distancing enforced by the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic. Our current reality has reduced the opportunities for physical interaction and the organic development of relationships, with many peoples’ main form of contact now being over a video call.

The greenscreen builds on this by creating a space which facilitates a digital landscape rather than a physical one, reinforcing the idea that the relationships we once cultivated in person have been moved to the digital sphere.

This is also the case for the relationship between the artist, artwork, and viewer. With much of art-viewing reduced to online exhibitions and viewing rooms, the transition of Eddie Peake’s work from in-person to pre-recorded performance echoes the anxieties surrounding the future of art in public spaces. It makes us question what our relationship with art will be in the future, with the ongoing pandemic making it more likely that we will have a less direct role in activating artwork as in-person spectators.

Eddie Peake’s ‘A Dream of A Real Memory’ emphasises the importance of reading between the lines and examining non-verbal forms of communication in their varying levels of accuracy. Playing on the boundaries of reality, dreams, and disfigured memories, Peake’s film continues to encourage an avenue for audience participation in his artworks despite the transition from in-person to on-screen.

The “story within a story” narrative teaches viewers to be cautious of accepting things at face value, as their spectatorship within the artwork is crucial to the realisation of the nature of each relationship shown onscreen. When faced with the rude awakening that is the breaking of the fourth wall and introduction of Peake’s ‘filmmaker’, it is emphasised that we need to define our own role as viewers – one which is more critical of the world and its capitalist markings. Viewers are encouraged to look harder when dividing between what is real and what is not, using this to understand what makes us come to our initial and final impressions.

The ideals we often perceive on our screens aren’t necessarily the real deal, and neither are the environments and relationships we conjure up in our dreams. Eddie Peake’s collaboration with CIRCA is a blunt message carrying this sentiment, enabling audiences all over the world to engage in an experience of emotional investment, confusion, and finally, the realisation of the various types of reality. In doing so, we simultaneously take part in the modes of non-verbal communication that make up much of Peake’s work.

CIRCA continue to make us question and anticipate the direction art is taking. With everyone anticipating the end of a very long and difficult year, it’s exciting to see the ways in which artists from all over the world are adapting their practice to maintain relationships with their audiences. Whether on the streets of Piccadilly Circus, on the walls of galleries and museums, or on our phone screens, there is a promise that while our relationship with art may change, it has yet to disappear for good.

Charlie Colville is the current Arts Editor for Mouthing Off magazine, an online platform designed to give young people the opportunity to find a new voice – a guttural scream loud enough to arouse fresh ideas, creative thought, and inspire artistic flair.