Eddie Peake: Rehearsal, Reversal and Carnival

Written by Gertrude Gibbons

Framed in a space of making, Eddie Peake’s A Dream of a Real Memory appears a rehearsal awaiting future performance. It seems as something not yet finished, anticipating conclusion, solution or closure; yet here at the Piccadilly Lights it is presented as complete in this suspended way. This sense of suspense perhaps draws upon its manner of presentation across thirty-one nights, which means that each episode, fragment of film, is stopped after two minutes, and interrupted by a full night and day, before the next fragment is played. Such interruptions to this seductive screen generally used for advertisement, feels as might sometimes be felt when, waking during a dream, there is an urge to force oneself back into sleep to finish the dream, either simply to continue it, or to solve it; to return to the place the dream left off, and glide over the disruption caused by waking.

There is a strangeness to the movements of the dancers, highlighted by the hypnotic and inescapable green, that works to alienate as well as seduce. Supposedly, narratives seduce through a promise of future closure, of reaching some kind of ending.[i] Since the strangeness of the movements, however, is created by the episodes running in reverse, its possible future closure is really in the past: the conclusion of the dance is always already done from the instant these screenings began on the first of December. In its inversion, it might suggest that in order to move forward with a work, and bring it into being, it is also necessary to look back. There is an aspect of ritual to this public exposition, a symbolic emphasis given to the digital time at which the episodes play running backwards: at 20:20 each day of the final month of 2020. This ritual feels all the more pertinent with December the month of the winter solstice; the day where the Earth tilts at its furthest from the Sun, and in some traditions represents the moment of the death and rebirth of light. It is a transitory moment of inversion: perhaps the world has turned upside down, back to front, mad. The sudden drop of a smile, laugh abruptly stopped, movement sharply stilled; the unpredictable irregularity of motion here edges on hysteria.

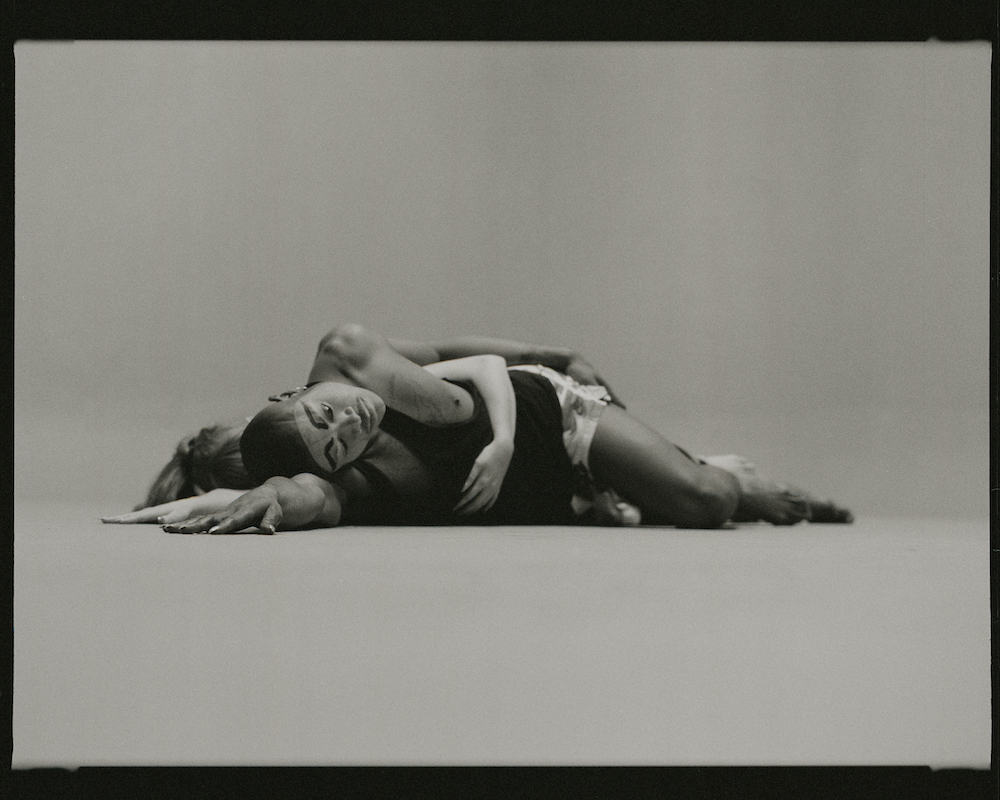

Symbolic reversals performed ritualistically are discussed by the Russian linguist Mikhail Bakhtin through ideas of the carnival and carnivalesque. He uses these terms to describe writing that not only illustrates the destabilisation of socio-political hierarchies, but also embodies the spirit, the laughter and madness, of carnival.[ii] There appears an atmosphere of the carnivalesque in Peake’s work, emphasised by the vibrant colours and painted faces of the dancers, which are reminiscent of the ancient Greek double masks of comedy and tragedy. Like the ambiguous opposing emotions conveyed by the ancient masks, it is often uncertain in this video work whether the characters’ expressions show laughter, madness, anger or distress. There is a sense of doubling, mirroring and uncertainty within their movements too, which fluctuate between formal and informal, synchronised and unsynchronised; they sometimes seem overtly self-conscious, aware they are being watched (an awareness emphasised by Peake’s own appearance filming within the work), and at other times they appear content, confident and focused in their own world. The interaction and distance between the two dancers also varies: while one might remain motionless, the other seems to widen the space of the screen, moving towards the edges, as though setting the parameters of this stage. The next day (or the next minute), their bodies are entwined; they appear to explore each other with intimacy. At some points within this intimacy, they rub at each other’s face paint, as if trying to erase these masks. Yet, inevitably, played in reverse, their apparent attempts to erase in fact work to conceal the faces beneath. The backwards look buries rather than reveals.

It is not only time that is reversed and played with here, but space too. The concave curve of the green cyclorama complements the convex curve of the Piccadilly Screen, such that the curve contained by the screen, and the curve of the screen itself seem to comment and converse with one another. The work is site-specific in this way, incorporating the space and time of the public screened location. This use of site is augmented through exploitation of sound: played in silence so that the natural sounds of the area continue uninterrupted and act as the film’s unpredictable and uncontrolled soundtrack. The external sounds become part of the dancers’ movements; and the spectators’ wait between episodes seems to become part of the work, such that the video work draws on this site temporally and spatially. This might be compared to the way in which carnival, and the temporary liberation provided by festivals, can enable commentary and consideration of circumstance by incorporating aspects of the familiar and confusing them with aspects of strangeness, so that the familiar can be looked at anew. Perhaps, in line with the tradition of carnival, as Anthony Gash writes of its subversive potential from the Middle Ages to present, these dancers are situated here “to inhabit a utopian upside-down world set free from hierarchy and material scarcity” which might, during “times of social crisis”, act in some form of political rebellion.[iii]

The sounds used in the film fragments as they are screened online adopt a different kind of naturalness of surroundings. Online, they are presented with their sounds of making, also played in reverse. These digital sounds of production emphasise the video work’s location in the space of making, as though enclosed in the liminal situation of rehearsal. With its green screen perhaps also reminiscent of those used for film editing, creating composite layers for visual effects, the figures in Peake’s work here at times seem trapped in a two-dimensional setting, in a digital world waiting to be made three-dimensional through a new backdrop. When Peake says this represents the “looping thought patterns of an obsessive, depressive or psychotic mind”, these appear as the sketched ideas of a performance before their realisation on stage.[iv] They move about in an unreal space, waiting to step into a different, new and altered backdrop.

[i] Ross Chambers, Story and Situation: Narrative Seduction and the Power of Fiction. University of Minnesota press, 1984, p. 214.

[ii] Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s poetics translated by Caryl Emerson. University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

[iii] Anthony Gash, “Carnival and the Poetics of Reversal”, New Directions in Theatre edited by Julian Hilton. Macmillan, 1993, p. 89.

[iv] Eddie Peake, CIRCA 2020

Gertrude Gibbons is a writer based in London. She studied Writing at the Royal College of Art, English and Related Literature at the University of York, and won runner-up for the Jacques Berthoud Prize in 2019. She has written for The French Literary Review, NERO Magazine, The Fortnightly Review, The Theatre Times, Witkacy!, Still Point Journal among others, and has recently written essays on Guillaume Apollinaire, Witkacy, Jean Cocteau and Philip Glass. Currently, she is researching Polish theatre and cultural reception in the UK and Italy, and writing about theories of absorption and seduction in the arts. She plays and teaches violin and has a keen interest in early music and opera. Other research areas include architecture, archives, graphics and design.