AA Bronson + General Idea: Going Viral

Written by Jack King

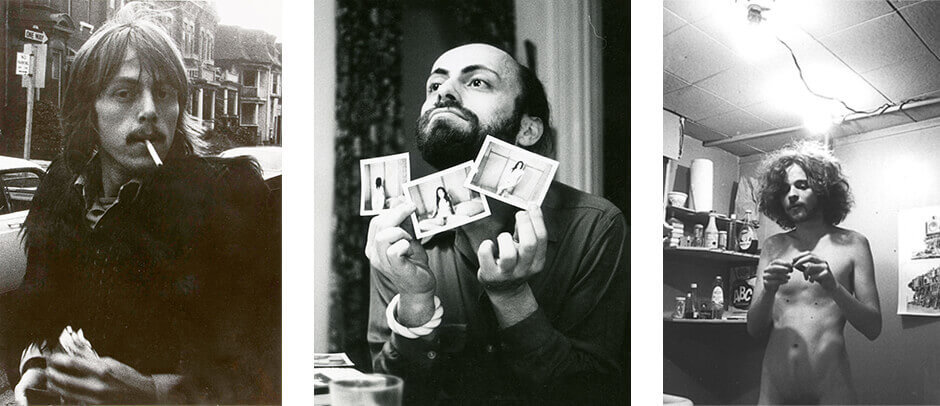

It’s 1986. New York’s HIV epidemic, the epicentre of a health crisis of which fires burn in most-all corners of the globe, has raged exponentially for five years. Thousands, disproportionately gay men, have already died; the state is, as will become its damning legacy, criminally negligent to the burgeoning disease, with President Ronald Reagan had not publicly uttered the acronym AIDS until the year prior. The broader public is callous. A trio of Canadian artists known by the collective moniker General Idea – formed of Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal and AA Bronson, all enigmatic pseudonyms – relocate to the city, where the art scene has suffered acutely.

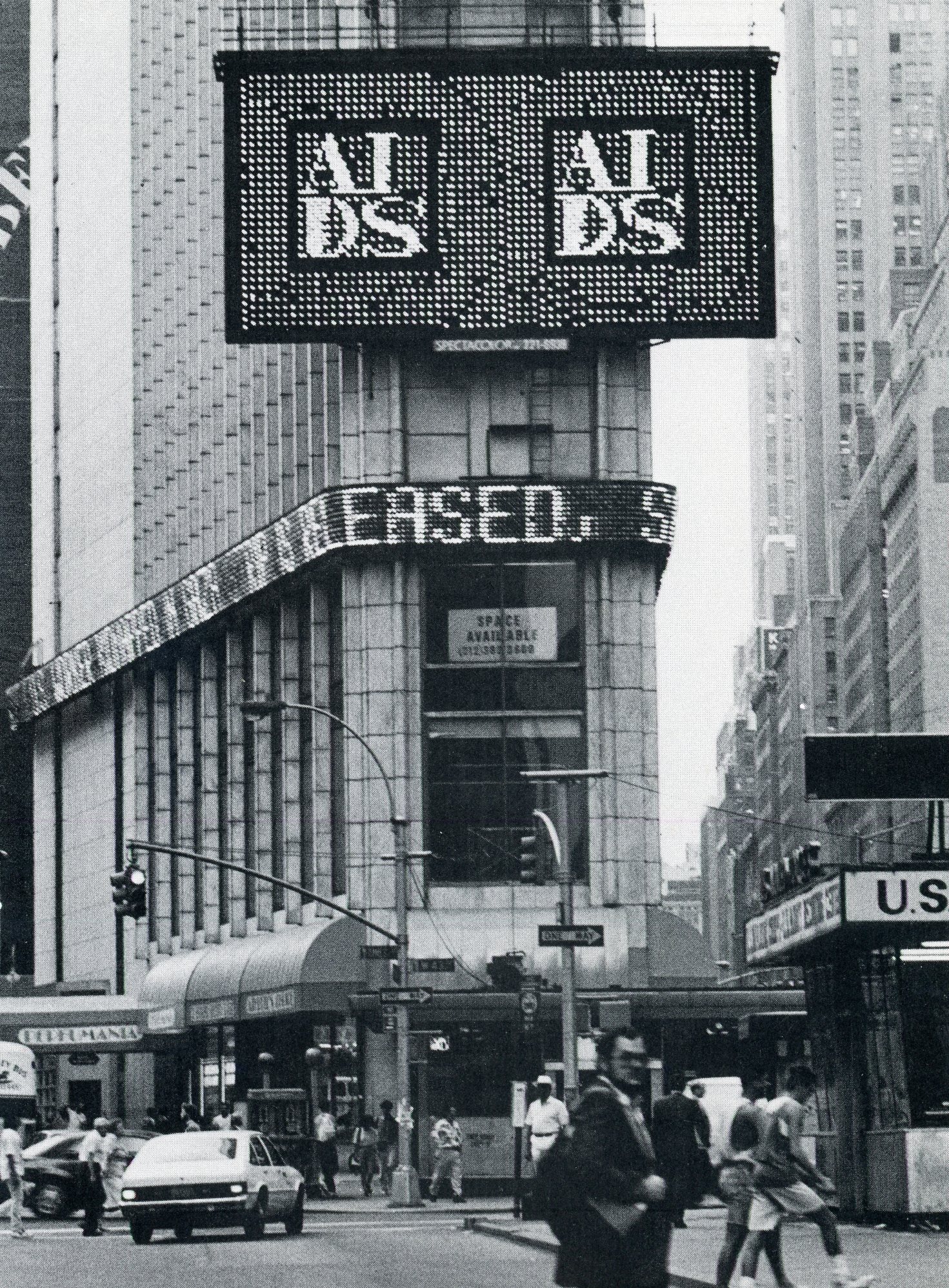

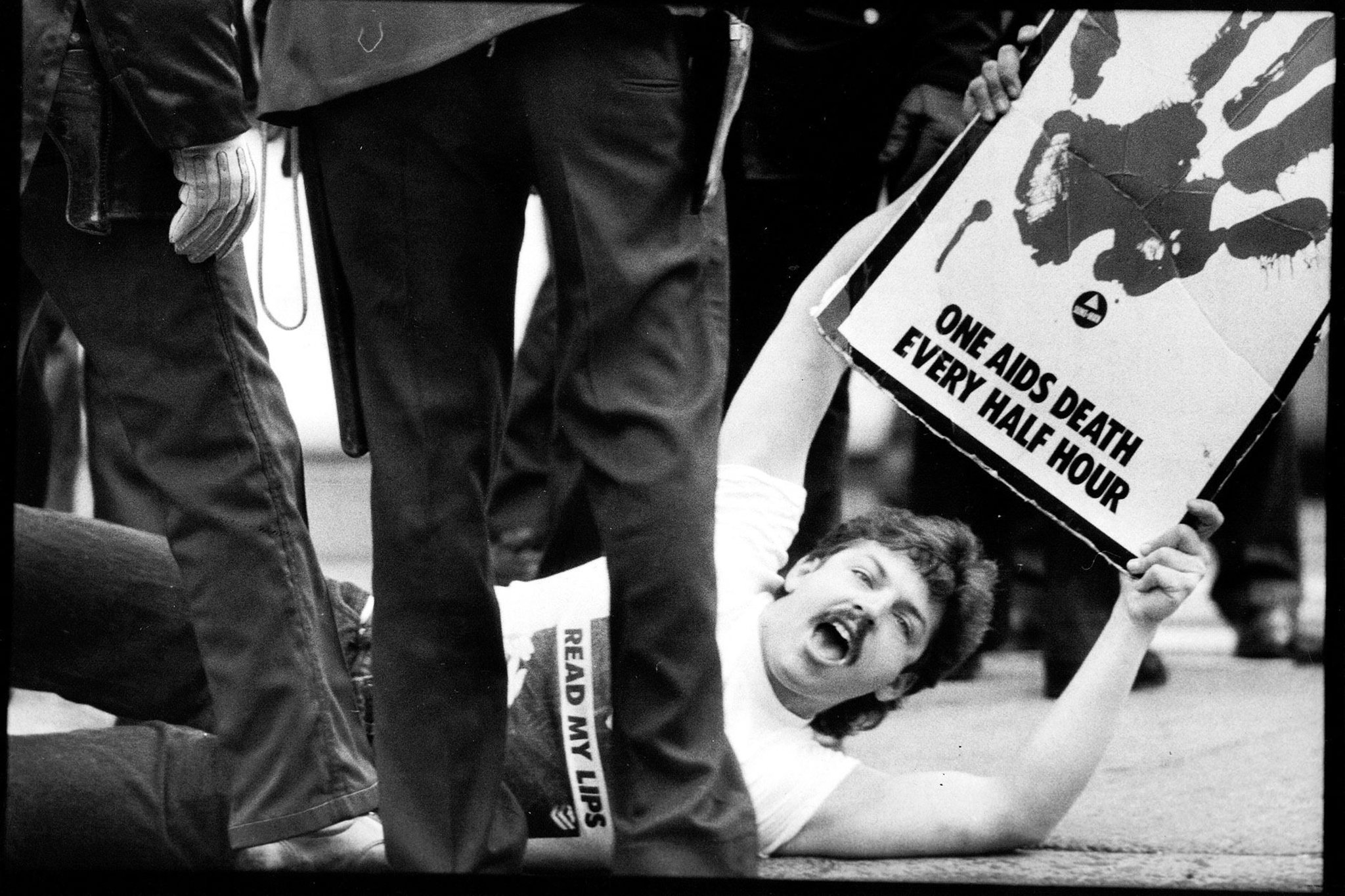

It was the year following, in 1987 – also, coincidentally, when the direct action group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was formed by a handful of activists, including the mercurial playwright Larry Kramer – that General Idea first put brush to paper on their AIDS image. Later turned into the Imagevirus poster campaign, it appropriated Robert Indiana’s Love, a characteristically bold pop art piece which has been formally replicated, homaged and parodied on everything from stamps to book and album covers.

The initial creation was for the benefit of AmFAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research. That spawned a series of paintings, the same motif replicated, as if left in a petri dish, in variously gaudy and kitsch colour schemes. From there, Bronson suggests, the project “took off” into Imagevirus, which saw posters wheat-pasted across sprawling city blocks, facades, trams, and subway cars in New York, San Francisco, Toronto, and Berlin: “What we were doing initially was more like an identity campaign,” he says in the film General Idea: Art, AIDS and the Fin de Siecle, “an advertising campaign for a disease, to normalise it, in a sense.” Pasted across walls in rigid uniformity, the image repeats like a virus, infecting brick and mortar. Imagevirus itself took on the characteristics of a self-replicating organism: indeed, to appropriate the lingo of the social media age, this was a viral campaign for an analogue epoch.

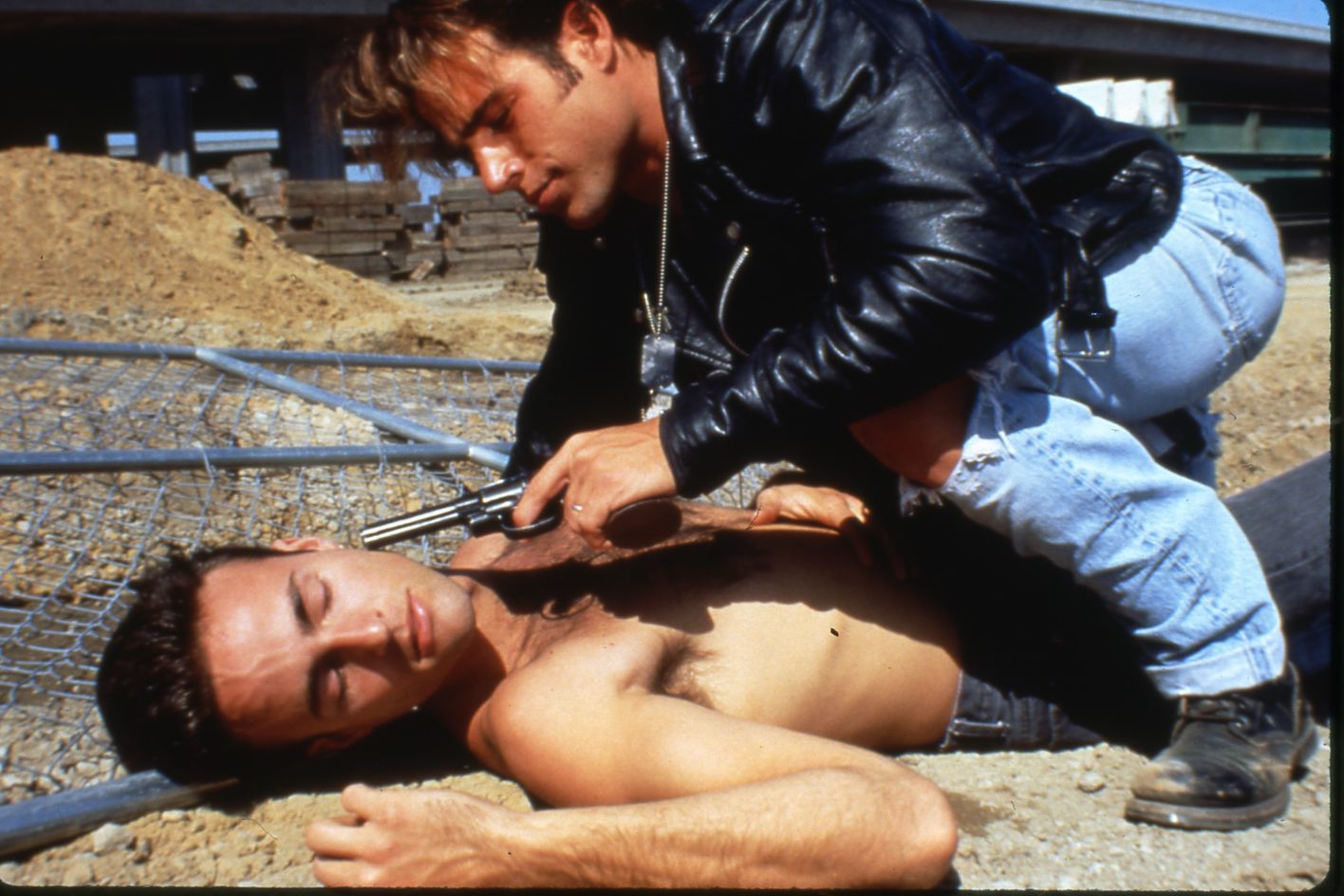

Unsurprisingly, AIDS inspired myriad works across mediums, from the moving image to theatre to, as with General Idea and the ACT UP-affiliated collective Gran Fury, street art and sculpture. Queer film scholar B. Ruby Rich has cast the crisis as pivotal to the genesis of the New Queer Cinema of the late-Eighties and early-Nineties, compounded by the queer world’s virtuous indignation towards Reagan and, crucially, the invention of the affordable commercial camcorder. And indeed, in numerous works of the movement explicitly deal with the epidemic in one way or another. Gregg Araki’s oft sought-after The Living End (1992) centres on two HIV-positive gay men running away from the law, Thelma and Louise style; Poison (1991), the anthology film that put the now-deified Todd Haynes on the global map, is a mosaic of bodily fluids centrally interested in the ‘other’ as a sequestered, persecuted body. (See also: his 1995 film Safe, starring Julianne Moore as a beleaguered suburban housewife afflicted by a mysterious, lesion-spawning disease.)

Adjacent to the New Queer Cinema, other independent American film titles tackled the epidemic head-on, oft with a focus on its devastating human effects. Canonically, the low-fi albeit stirring Buddies (1985) is usually taken as first-out-the-gate: directed by Artie Bressan, Jr., a queer pornographer by trade, it observes the relationship between two gay men, one with HIV and the other without. The year after, generously soundtracked by Bronski Beat, Bill Sherwood’s Parting Glances (1986) gave Steve Buscemi his first significant role, portraying a man with AIDS on the precipice of his death. It approaches the subject with refreshing candour, and Buscemi’s character fondly reminisces over the decade prior, an oft-forgotten period of queer hedonism and political liberation in the shadow of the Stonewall Uprising. Both Bressan, Jr. and Sherwood would die of AIDS-related illnesses.

One cannot take a whistle-stop tour through the cultures spawned by AIDS, of course, without turning attention to the stage. It’s here, after all, that arguably the most notorious piece of queer agitprop was conceived: Larry Kramer’s virulent, no-holds-barred roman-à-clef, The Normal Heart (1985), which doesn’t simply repeat the story of the New York crisis’ early years so much as a roar with resentment at the negligent political class. Angels in America (1991), Tony Kushner’s oft-revived two-part epic most recently seen at the National Theatre helmed by a decidedly high-camp Andrew Garfield, bubbles less with anger than a solemn inevitability, more a vigil than the deluge of mortar fire. Taken together, they are two works, however formally discordant, that effectively communicate the devastation – emotional, and physiological – of this terrible historical moment.

Forty years on from this global pandemic, new public interest has been spawned by a proliferation of popular cultural works in the West, frequently replicating prior narratives. Robin Campillo’s 120BPM piqued the interest of the arthouse crowd in 2017, and more recently, Russell T. Davies’ It’s a Sin (2021), a humanistic melodrama centred on Britain’s AIDS epidemic, captured the zeitgeist. Quantifiably one of the most popular TV shows of the year – even if some contest its artistic merits – it demonstrably increased public awareness around the virus, both as a history and of its present epidemiological impact. What was once a genocide of neglect and apathy, as the playwright Matthew Lopez once put it, has mutated into an epidemic of intrigue – at least, if not empathy – transmitted through the vector of artistic reproduction.

It’s fitting, then, that Bronson and General Idea’s Videovirus takes the base concept of viral replication in the distribution method of Imagevirus and evolves it formally. In the piece, the AIDS image literally duplicates itself, spreading rhythmically – as if in the patterns of dance – to each edge of the frame. While the dissemination of AIDS awareness is perhaps not as urgent as it was thirty years ago, with the current generation, not least among those who identify as queer, better informed about the virus than ever before, it remains a bold and pertinent statement.

Jack King has written features, reviews, interviews and profiles for New York Magazine, The Guardian, BBC Culture, i-D, GQ, The Face, Inverse, the BFI, BAFTA, Little White Lies, The Quietus, NME and more.

He managed Curzon Goldsmiths, an independent 104 seat cinema based in South East London, from September 2017 through to June 2021 before taking up an additional role as the venue’s Programme Curator in October 2019, directing both the Curzon Goldsmiths programme and the annual Goldsmiths film festival, Gold on Film.