James Barnor: Ever Young, Ever Endearing

Written by Christian Adofo

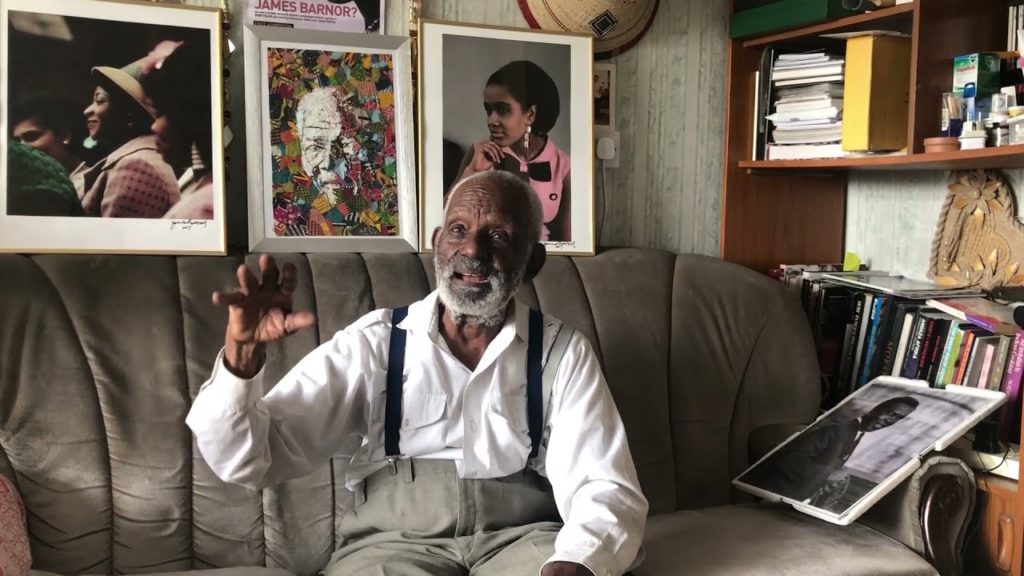

“A civilisation flourishes when men plant trees under which they themselves never sit. But it’s not only plants-putting something in somebody’s life, a young person’s life, is the same as planting a tree that you will not cut and sell”. A pensive perspective from James Barnor, a British-Ghanaian photographer by practise yet his words belie a creative polymath whose repertoire spreads across five decades from pre-independence Ghana to his relocation to London in the 1960’s and back to Africa again.

Through his archive, storytelling is at its core and the above mindset personifies an inherent foresight for legacy encouraging creativity and inspiring new generations regularly whether through fresh introduction via sharing of his images on social media or facilitating the projection of Black Africans not only in Africa but in the wider diaspora within migrant communities in the West. This worldly context portrayed through his images from his archive serves as the erudite epicentre for a series of three new films titled ‘Past, Present, Future’ for CIRCA in collaboration with The Serpentine who will host the first major survey of his James Barnor’s work in London this May.

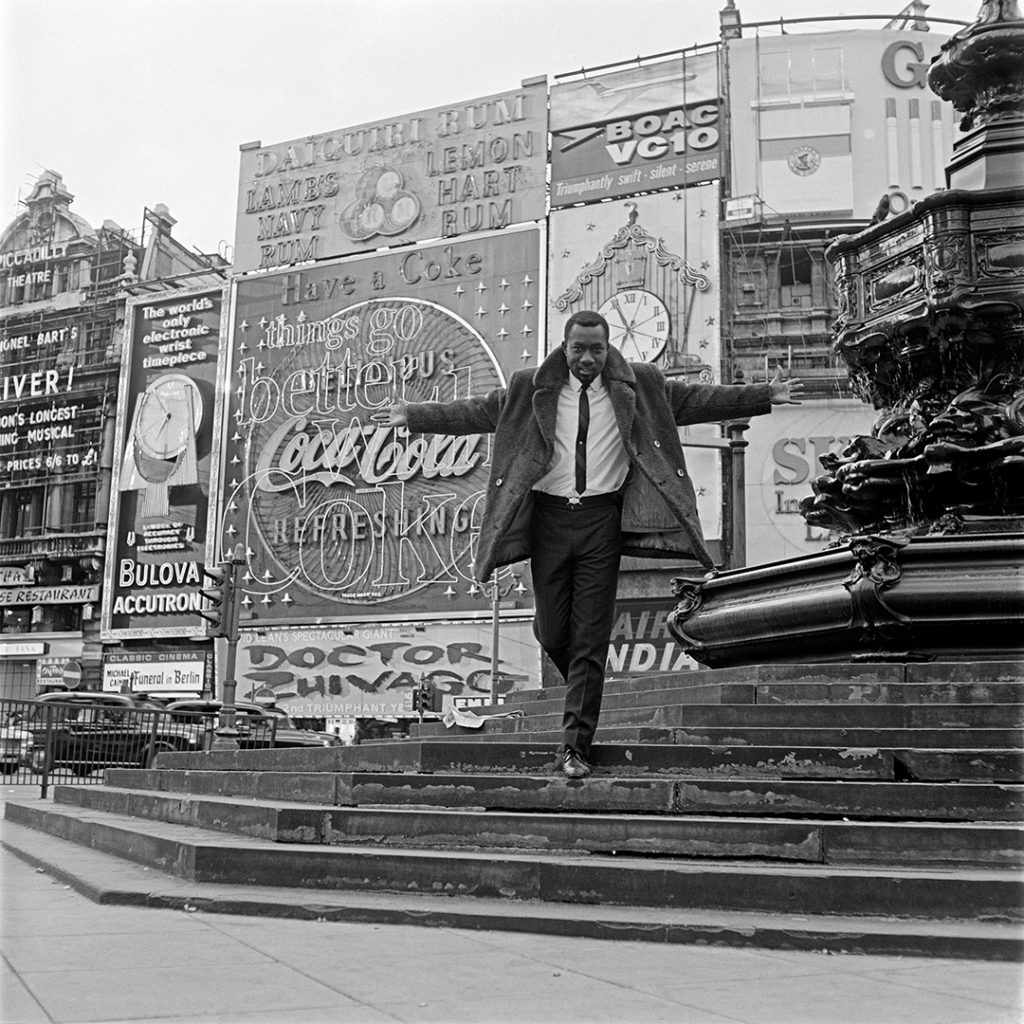

It represents an organic continuum that looks forward as much as it looks back in reflection, chronicling societies in transition in the post-war epoch. This cyclical creative conversation is evident through one of his most celebrated images where he captured Ghanaian BBC broadcaster Mike Eghan with the iconic Piccadilly neon lights in the background in 1967 and these newly commissioned films will return Barnor’s work on the screens at Piccadilly Circus.

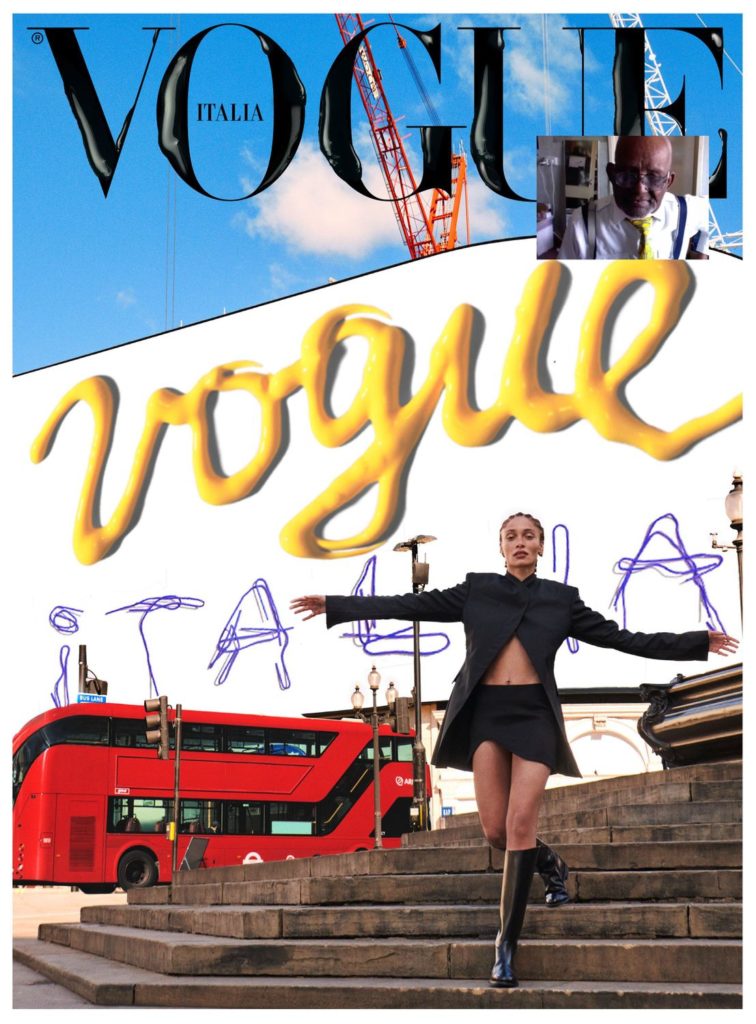

“The biggest contribution I could provide to James’ career was allowing the new generation to understand James’ relevance to the history of photography by creating something which wasn’t just new but it was sort of an interpretation of his past.” says Ferdinando Verderi, the creative director of Italian Vogue focused on the Past segment of the film series and was tasked with responding to rarely seen imagery from the archive.

A synergy with Barnor’s work is reflected through his first cover for Italian Vogue where the DNA theme revolved around identity, heritage and the family of the three models featured. A sense of expressing early multicultural society far from a monolith through style is prominent from past to the present day for both. Verderi adds “It’s clear that the symbolic line I trace along these images has a very metaphorical meaning of tracing a history which is not necessarily chronological but is the history of a world and a community which James documented and created.” One image in question from the archive which inspired Ferdinando was that of Nigerian model and actor Marie Hallowi on a corner of Trafalgar Square in the presence of the landmark’s pigeon tenants. It emanated from James’ period with the seminal DRUM Magazine, Africa’s first black lifestyle magazine where he was in the midst of capturing Sixties London. Verderi reflects “(It) had a real strong sense of time warp between today and the time he took them. They are clearly images which have a period touch to them but they feel so ageless in their effort and context of today. He concludes, “These images remind us of a certain age in people regardless of the generation they belong to… I am always fascinated about how young people of today relate to people in the past.”

The reflective state in which images can teleport you to allows a comprehension of the context of the moment stood still despite time passing and is a strand brought to the Present segment of the film via a multimedia approach. “Showing me a photograph of a Ghanaian woman he had taken in the sixties, he said: “She was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen.” It struck me later that this statement said more about the nature of photography, as well as the subjectivity of beauty” says Olu Michael Odukoya, a London-based creative director of Nigerian heritage who shares reflections of his first encounter with Mr Barnor. His own response to James’ archive is a project titled “Ghana Monderain-Audio Sound” touching upon the themes of women, Modernism and its use of colour and the passage of and mutability of time. On the theme of women, Odukoya resonated with his documentation of black women through his photography. He explains, “Both women and black subjects are seen as being overlooked and under appreciated, despite having been depicted in art for as long as art has been produced” Odukoya further adds, “Black women have always been the nucleus of black society, which is in many ways more matriarchal than patriarchal. I am interested in using the fact that Barnor’s work was often ahead of its time to produce a collaboration that feels genuinely contemporary and fresh.”

Another aspect of Odukoya’s focus on the Present is reflected in his explorative disruption incorporating the red, green, gold and black colours of the Ghanaian flag designed by the late Theodosia Okoh into a painting by revered Dutch Modernist artist Mondrian. It’s a deliberate juxtaposition which reframes the narrative of the black experience in a space of high culture and reimagines it in a utopian sense. Olu says “What if the culture we were familiar with had privileged black or African experiences instead, so that this was what had become the familiar aesthetic of Modernism, rather than that of Mondrian?” He explains “It suggests an alternate art history, with a freer creative exchange between Africa and the West.” It further aligns with the continuity in Barnor’s archive as he was the first to introduce colour photographic processing to Ghana and bring further richness to the global projection of livelihoods and landmarks in the West African nation setting up the first colour processing facility there in the 1970’s.

The time and perspective theme of Odukoya’s work is explored through an audio-visual component. The former consists of ten recordings by a female reader, who describes images of women by James Barnor: the subject’s hair, clothes, posture and environment, her expression or apparent mood. Whilst the latter has an abstract approach portraying a number of contrasting scenarios which project beauty in his Olu’s description as “much closer to a feeling—of warmth, of happiness, of goodness—than a single image of a person.” In this context, it’s a constant and ever-shifting conversation not only with Barnor’s archive from the past but equally enables us to take stock of his work in the present day.

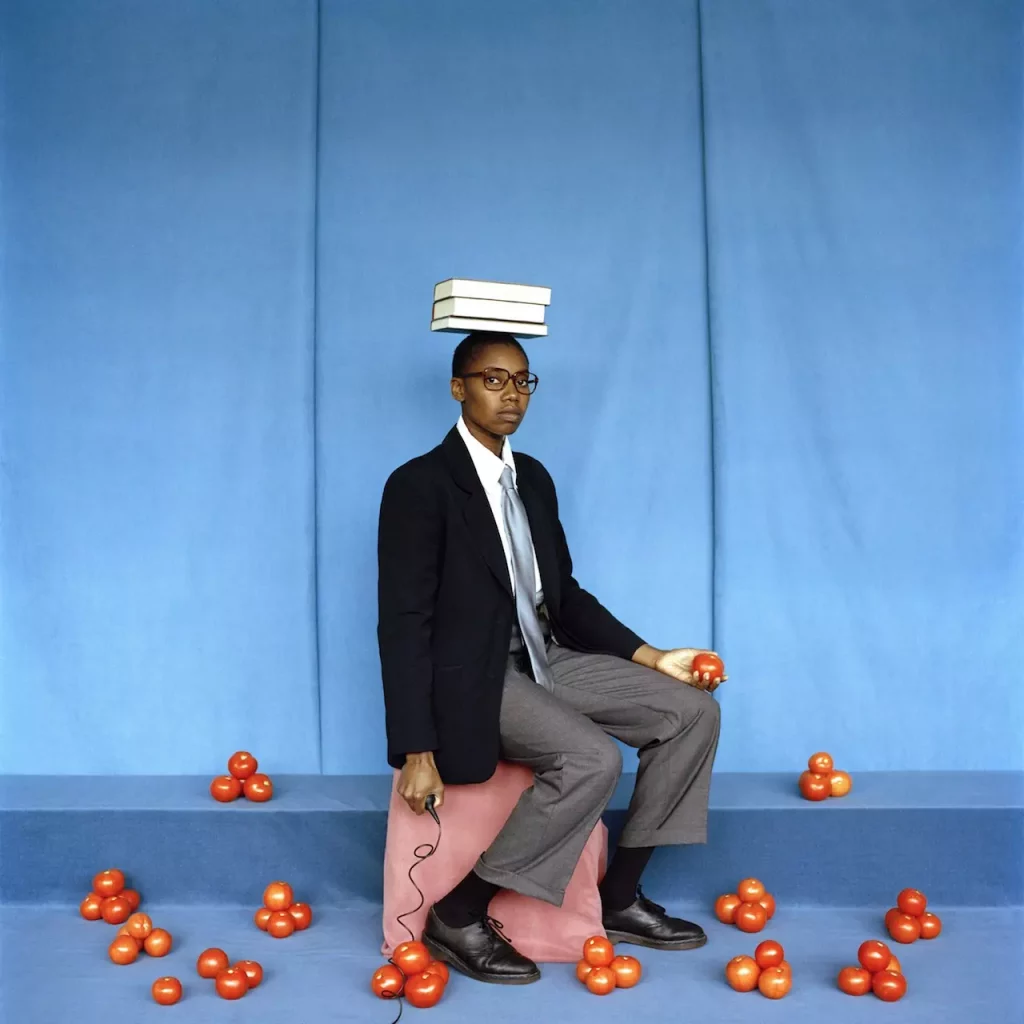

In the Future segment part of the series, the spotlight fell on five emerging photographers including Adama Jalloh, Silvia Rosi, Lebohang Kganye, Thabiso Sekgala and David Nana Opoku Ansah from the African diaspora. All very much aligned with James’ reemergence as a hospitable role model for a new generation of artists who have an example to show their parents of diasporic excellence in the arts. Led and selected by Awa Konaté, founder of Culture Art Society, a platform looking at the intersection of critical studies and art theory to delve into the cultural economy of African archives both on the continent and in the diaspora. “It has been like excavating so many complexities that exist within it”, Konaté reminisces on her relationship with the ample archive. She further explains, “Whether it’s a reading of migration or the Black British visual canon for example that James Barnor very much exists within or whether it’s about rethinking the history and also how the development of photography is such an integral framework for black communities to remember themselves against an external gaze.”

Despite the work consisting of copious images from the past, Konaté along with the curatorial team at The Serpentine would regularly posit future reflections on the themes that emerge and still hold resonance to the present experience of being a black African dependent on location. “It’s very timeless so it means a work may have been produced fifty, sixty or one hundred years ago but there is always going to be somewhat of a continuum or a reflection in the contemporary and present moment of their work.” This essence of timelessness was reflected in the selection of the five aforementioned photographers thinking about how their practises were relatable to different stages of James’ career. On the continuity of the photographers and Barnor’s work, Konaté breaks down each “Silvia is a Togolese-Italian photographer who creates a really rich body of studio portraiture that you would see in your family albums but she uses them as a way of almost reinterpreting the studio practise as a space of not just reinterpretation but also re-intervention of one’s self. I find this to be so significant to James’ Ever Young studio period. He founded Ever Young in the early context of Ghanaian independence and the early context of this idea of nation building and remaking of one’s self.” She adds, “(the late) Thabiso Sekgala has an incredibly rich body of work that documents a generation of South Africans that were born after the abolition of apartheid. His work conveys such tenderness because it’s about trying to re-navigate not just space, time and place but also thinking about how they reconfigure what you are trying to capture with the eye. This really reminds me of James’ work when he returned to Ghana after a decade of being away in Europe”

Accra based photographer “David Nana Opoku Ansah actually quotes James Barnor as a direct influence in his work but (is) also breaking away from that interpretation.” South African Lebohang Kganye “is famed for double portraiture where she is almost re-staging an intervention into her mother’s photo album shortly after her mother had passed away. I find that so significant to James’ work because this is going to be his biggest retrospective and his biggest survey of work to date. Within this process which has been a constant coming together of things has been a re-intervention into the archive excavating histories, finding out what people are, what part of James’ history do we know and what part of James’ history do we not know.” Adama Jalloh who creates rich black and white portraits documenting the cultural landscape of London and the way it is undergoing quite significant social, political and cultural transformation in photography and through her eye you are seeing that it takes a lot of familiarity but it also takes a lot of tenderness and distance to be able to document the society that she shows. “Taking photographs of black migrant communities at that time in constant flux of transition coming from what was then the Commonwealth and coming to the UK undergoing such cultural shock and also realising you are close to this culture but also very much at distance from this culture.”

I query Awa on the juxtaposition between education and building a creative career that has given James the vim for longevity in his craft and she makes a poignant last reflection, “You have someone who actually pursues an education and tries to really make a very very rigorous knowledge about their work and share it with their people in such an important way of being communal.” Following in the vein of early facilitative spaces such as the Black Cultural Archives and Autograph, the scale of his forthcoming perspective at The Serpentine is one in which Konaté feels will open “a new foray in how to articulate and understand why Black British photographers are important to the repositories of British visual culture and British photography”.

For the affectionately known “Lucky Jim” being the seed of creative conversation at 91 years young is a harbinger to planting deep roots he has nurtured and yielding his harvest not only across physical location but inspiring a new creative mindset for the branches of future generations to come.

Christian Adofo is an established writer, cultural curator and author based in North London. His passion for writing looks at the intersect of heritage and identity in Music and Culture across the cultural landscape. He is a regular contributor to publications including OkayAfrica,Straight No Chaser + We Jazz Magazine acknowledging seminal figures and interviewing burgeoning talents across the creative spectrum within the African diaspora. He is the Creative Producer at Crudo Volta,a visual collective focused on documenting contemporary youth and music cultures across Africa and the diaspora. His forthcoming debut book A Quick Ting On Afrobeats is released via Jacaranda Books in October 2021 as part of the first ever non-fiction series celebrating Black British culture.