Kembra Pfahler in conversation with Josef O’Connor

Josef O’ Connor: It’s half midnight on the 4th of April, 2024. I’d like to suggest that in the spirit of live performance, we commit to transcribing everything we say in this conversation.

Kembra Pfahler: If this is just in the spirit of my live performance, I usually sing. I never really talk.

JOC: You are welcome to sing rather than talk. I wanted to start with our CIRCA collaboration, which felt like a love letter, a special journey we went on together. People often ask how I pick the artists and I now kind of believe that the artists almost pick me. And that it’s my job to respond and follow that energy. After learning about your path as a teacher, The Manual of Action revealed itself through phone calls and brought us to know each other in a very short timeframe, and I feel it does quite an effective job of telling the story of Kembra Pfahler.

KP: Thank you Josef for saying that. One of the reasons I gravitated towards CIRCA was because I rarely feel heard or encouraged to describe my work. Not everyone is interested in extreme performance art that involves complete head-to-toe transformation, nudity, props and homemade costumes. Everything is pretty DIY with The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black and there was a lot of joy in this process. I think that joy, pleasure and fun in doing really serious work is rare. I felt encouraged and appreciated by CIRCA. I didn’t feel pushed to put myself into a branded machine. I think that we’re a brand of outsiders. We’re an unbranded little group of people and am always surprised when people even know about what I do. I feel like we’re extremely unpopular. It’s rare to feel that the essence of what I do is understood and I am grateful to you for that.

JOC: For me, you embody the essence of a true artist. You’re fully committed to being who you are. There is not an off switch to Kembra Pfahler. If life—be it a practice—then the journey that you are on is in itself art in the way that you approach everything. I suppose that influences the way that you’ve developed philosophies around Availabism and all your vocabulary, but also the transgression between cinema, music, and art. It all becomes art. Today everything seems to be hyper-strategized, hyper-organized, hyper-market aware, hyper-gallery focused. The magic of downtown New York is what has given birth to the art market we know so well today. If you think of artists such as Basquiat and Warhol, they were born out of availability, of using what was available, such as empty buildings because the city collapsed. How did being an artist in that ecosystem change from the 80s to the present day?

KP: We spoke about mutability when we were filming the other day. There’s a feeling about being very much connected to my own aesthetic and my own ‘vocabulary of images’, but at the same time remaining teachable. If I hadn’t made the film that we did for CIRCA the other day, which was done with such a collaborative spirit, I wouldn’t have learned about a new makeup technique by just adding a little water. When I started putting make-up, I was using what was available in my surroundings which was house paint and Plaster of Paris. I’ve gotten so many different show business injuries over the years before I learned from my own mistakes. I still want to welcome happy accidents and interesting surprises. Change is very important to me. I remember that in the 80s and 90s, I did a performance where I stood on my head and cracked an egg on my vagina, and I remember my best friend saying to me, ‘When are you going to stop doing that? Haven’t you done that enough?’ And I realised and said to them that it is part of my vocabulary of images, and I’m never going to stop doing that. As much as you might think it’s over, it’s just something that’s a part of me that I never want to stop sharing. A live performance is like a song that you can play again and again. If I became closed-minded and blinded to any change, then I would avoid happy accidents which are to me a great deal of joy.

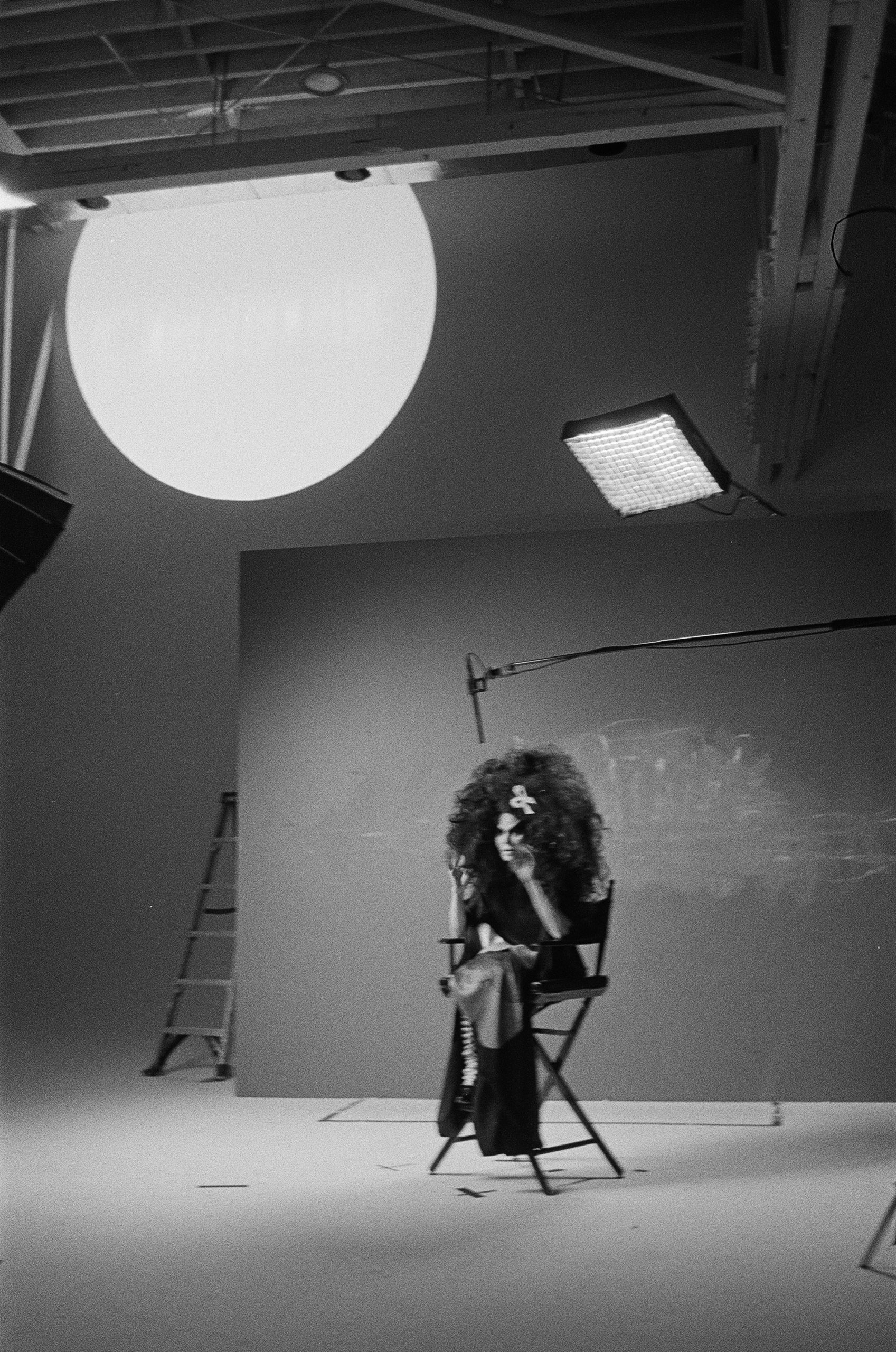

JOC: You allowed us to go on a journey to create something new together without even knowing what it was going to look like. During our collaboration, I felt myself practicing Availabilism or acknowledging that I already practiced it. I realised that what resonated was this idea of a higher power, that the work will reveal itself to us. There is something really powerful about allowing room for magic to be created. This is what happened when we were on set when we had a loose idea of what we wanted to do and it just became a live performance as we hadn’t rehearsed it. The 2.5min live performances couldn’t be refilmed because you could only erase the previous word on the red chalk board once. How did these core ingredients of your practice manage to come together in the space of 2.5 minutes?

KP: When I’m on film, I’m not a method actor. I call myself an anti-naturalist which is the complete opposite of method acting. I’m working from my memory, remembering traumatic or happy emotions that happened in the past. What I like about live performance is that it taught me to exist entirely in the moment and the present. If the artwork, the poem, the image or the piece itself is strong enough, it always sticks. The day we filmed, I had a feeling of faith and confidence that what we needed was going to present itself. Even if we couldn’t carry my big Christmas tree, and my Statue of Liberty out of the apartment, I was still able to bring my bowling balls. It happened also thanks to the incredible team you assembled. Something that I learned during this process is to minimize instead of maximizing. If one minimizes, happy accidents are most likely to happen.

JOC: I could not agree more. Scaling back was such a powerful lesson for me as well, because I realised you were enough as Kembra. There was no need for props. When we were painting your body I was aware of the fact that your body was the canvas which makes me think of the way some artists have acknowledged body beauty as perfectionism. I’m intrigued by the influence of Hollywood cinema on your practice and what brought you from LA to your red apartment in New York.

KP: If you think about it, the United States are a film set in itself, literally. The light in California is unparalleled. And there was space to build film studios. That all happened before Hollywood blew up. I feel that everyone who grows up in Los Angeles is essentially born into a show business of some sort. You’ve got people working in the makeup departments and the lighting departments, making costumes, making commercials, making films. In my family, generation after generation, people have been interested in film. I grew up on the beach in Hermosa Beach and was a surfer. I was from a surfing family. My dad made a surfing film called “Endless Summer” and films with Bruce Brown, such as “Slippery When Wet”, the first of the great surfing films ever created. I took that film with me to New York and utilized those film techniques in the 80s because it was very performative. There was a use of a 16-millimeter camera, and for the soundtrack, there was a live band that played along. When I was in LA, since I was a petite natural blonde surfer, I was being coaxed to be a model. The first commercial I did was for Kodak and I had to sit on the stomach of a very large man on the beach. While I was doing it I had a feeling that it was something I didn’t want to do. I didn’t want to sit on a big person’s tummy for ten hours and pretend that I was taking pictures or selling Kodak films. When I was young I always thought that I wanted to do something of my very own, which had nothing to do with any of the things I was seeing in California. I didn’t like the way they made films. I just thought I needed to go somewhere else, like New York, where I could learn and be myself. I was always looking for people I could identify with and there is one artist who lived in Santa Monica that inspired me: Kenneth Anger, who was born four blocks away from where I was born. His books ‘Hollywood Babylon’ were really important to me. When I started doing my work around 2008, I got to spend time with Kenneth in England during a residency in London. At that time, we got to speak with him about growing up in Los Angeles: waves and waves of body shame, waves of dysmorphia, and just waves and waves of humiliation. So much misogyny. I always felt devalued by the adults around me. They would look up and look down and then throw me away. And I always thought to myself, I never want to grow up to teach young artists or to treat young people or young artists like that. It was one of the reasons why I started the course because so many things happened to me when I was developing my vocabulary of images. I always thought to myself, I’m going to remember what this feels like because I never want to do this to a young artist.

JOC: While shooting, I noticed that sometimes you would put your hand on your hip and pose as if you were in a modelling contest. At that moment I realised that you knew these videos would appear on billboards and you were mocking the culture of Hollywood, or the idealised expectation you mentioned from childhood. Is beauty an important aspect of your practice?

KP: I think we all have the right to exist and that beauty is very subjective. Each one gravitates towards different things. Not everyone thinks that blackened teeth and full body paint are beautiful. The actress Karen Black, wasn’t a typical beauty, she was strange and exotic and often teased about her appearance when she was in Hollywood. She had strange eyes. I had the chance to meet her, she came to one of my first concerts in Los Angeles as The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black and was so kind to us. I think she intuitively felt like we weren’t trying to mock her, or we weren’t trying to be mean-spirited towards her. What Hollywood actress would show up to a concert at one in the morning that was named after you? She told us: “I’m not sure what it means, The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black. Does it mean I’m voluptuous?” She never sued us for using her name, she acknowledged us as a positive art project. Going back to your question, I think that I intend to create a new paradigm of visibility, of what I consider beautiful. I always had a desire to insert myself into the culture. Bob Guccione got me into Penthouse Magazine in the late 90s, they published a picture of me with my vagina shut. I live on a block where there is a fire department and they would always tease me. When I walked by, they’d call me Elvira or Frankenstein because of my goth look. I remember that when Penthouse came out, that was the first time they were ever really nice to me. Still in the 70s or 80s while I was walking around with this kind of makeup people just wanted to kill me and throw Coke bottles at me. There also was a lot of bad reaction to the way my band looked but we just kept doing it, kept showing up, and kept getting jobs.

JOC: When we first spoke, you immediately described yourself as an educator. That was inspiring as I thought it was the antithesis to your own vocabulary of images and contrasted against how people might see or even judge you. I felt a responsibility to present an image of you that the world might not have seen or heard before. Could you talk about what The Manual of Action is and what your hopes are for it?

KP: The Manual of Action was one of the first things I did in the 80s in New York City. It was the first performance I curated and that I participated in. My greatest hope is that the people coming to see these films and experience the classes will be encouraged to investigate their creativity, as I did. Sometimes it’s difficult to organize your thoughts around performance, drawing and creativity. The Manual of Action is a kind of gentle discipline. It’s a way to help people organize their thoughts and practices daily to help their creativity emerge. I would like people to see creativity as a muscle that needs to be exercised. I believe each of us is creative. I’m not speaking about becoming a famous artist or even becoming an artist, it’s more about teaching people how to give value to their creative thoughts and destitute devaluation. The Manual of Action is me sharing, it is the antithesis of being destructive. I don’t like the idea of ever causing harm in performance. Hurting anyone, hurting myself, hurting others. It’s very important to me that there’s love and caring in performing. Whenever I’m working with young artists who want to move towards some destructive element, I usually encourage them not to perpetuate a negative, romantic, destructive idea of an artist’s life. I think that’s got to be flushed down the commode. I think there’s no room for that right now. The room for being destructive and hateful towards oneself. Life’s already so difficult.

JOC: True, love has become a rebellious act in the world we’re living in… In fact, the huge room inside Vivid Kid where we filmed The Manual of Action was filled with a lot of love and admiration that day. Do you have any memories from the shoot that you’d like to share?

KP: Oh my God, there are so many as everyone in the team was so incredible. Still, there was a moment when Jasper (Rischen) looked at me and asked me how was I doing. I was shocked that the filmmaker would look me in the eyes, put his hand on my shoulder and tell me: “Is there something I can do?” I just thought: Who is he talking to? Is he talking to me? Is this Robert Altman or Jasper? He had such an interesting way of dealing with us. I wondered what it could be like for him to look at this explosion of activity and still be present and wonder about my feelings. He wasn’t cracking a whip. He didn’t have a gun to my head. That sentence echoed also when I was going back home. I kept hearing it over and over again. Something else that stayed was when you added water to my body paint which was so eroded and cracking. And I just kept thinking: just add water, add water, add water. I felt like suddenly becoming a flower. It made me feel alive and prompted me to continue our exploration. It’s interesting because in the following days, everything reminded me of the shooting. I was in the bathtub, completely covered with body paint and was looking at my cell phone and thought: I don’t need this phone anymore. My face had been glued to it for months. I just added water to it and it became extinct. Overall, each class we enacted was memorable. Building the chalkboard where we wrote the classes’ names was like building the pyramids. I couldn’t figure out how you did it. I never wanted to leave the place. I wanted to show everyone around the world what we made.

JOC: It was a revelation for me as well. The chalkboard became a painting because the process of erasing each title left behind this detritus of chalk which evoked impermanence. I think we managed to capture the idea of action. To witness performance you have to be there and we were there. I also loved the way you added letters to the space with your handwriting, went a bit higher than I thought and then brought it back. I was always worried that you would run out of space to finish the word but still, everything had to work within one take because it would have been inauthentic to repeat it. Everything had to flow. I found these rules reassuring. There were some higher powers in action as well. How did we pull together a shoot in such a time frame? How did we manage to execute 12 films in one day? How did we manage to get a wedding cake? How were you able not to fall from the table while sitting on the cake? So many things could have gone wrong, but didn’t…

KP: There were a lot of miracles.

JOC: That reinforces my belief in art. I’m intrigued now to see what these miracles are guiding. What has enlightened me, is that it’s the act of creating without knowing why you’re creating. And I think that things shouldn’t be made to be sold. You know, things sometimes should just be made for the journey. And I’m honoured that you’ve agreed to join us on this one.

KP: I feel like art, poetry, music, fashion design, lyrics, these things can help change the world. I can’t figure out how we are going to change the world except by redecorating it or giving it a new soundtrack. I love what I’m doing so much. It’s such an incredible experience to get to wake up and be an artist and do projects such as The Manual of Action for CIRCA. There must be a way to change the world and we should make it happen. .