David Hockney: Let The Sunshine In

Written by Henry Little

Dawn. A blue sky shot with red. Silhouettes of sleeping shrubs. A single bird traverses the full width of the horizon. A child-like sun, wobbly arms for rays, rises in the distance. Higher the sun rises, a second corona of wobbly rays appear. Higher and whiter the disc rises, until a third corona of longer fingers extend out towards the viewer, licking the foreground. A fourth spiral of yellow rays now fills the thin band of the horizontal composition, on the cusp of enveloping the entire scene. Thicker, heavier lines appear, ray upon ray. The scene fades to vivid, bright saturated yellow. The yellow of cartoon lemons and street lamps. The work’s title is etched in shaky letters across this final backdrop: Remember you cannot look at the sun or death for very long.

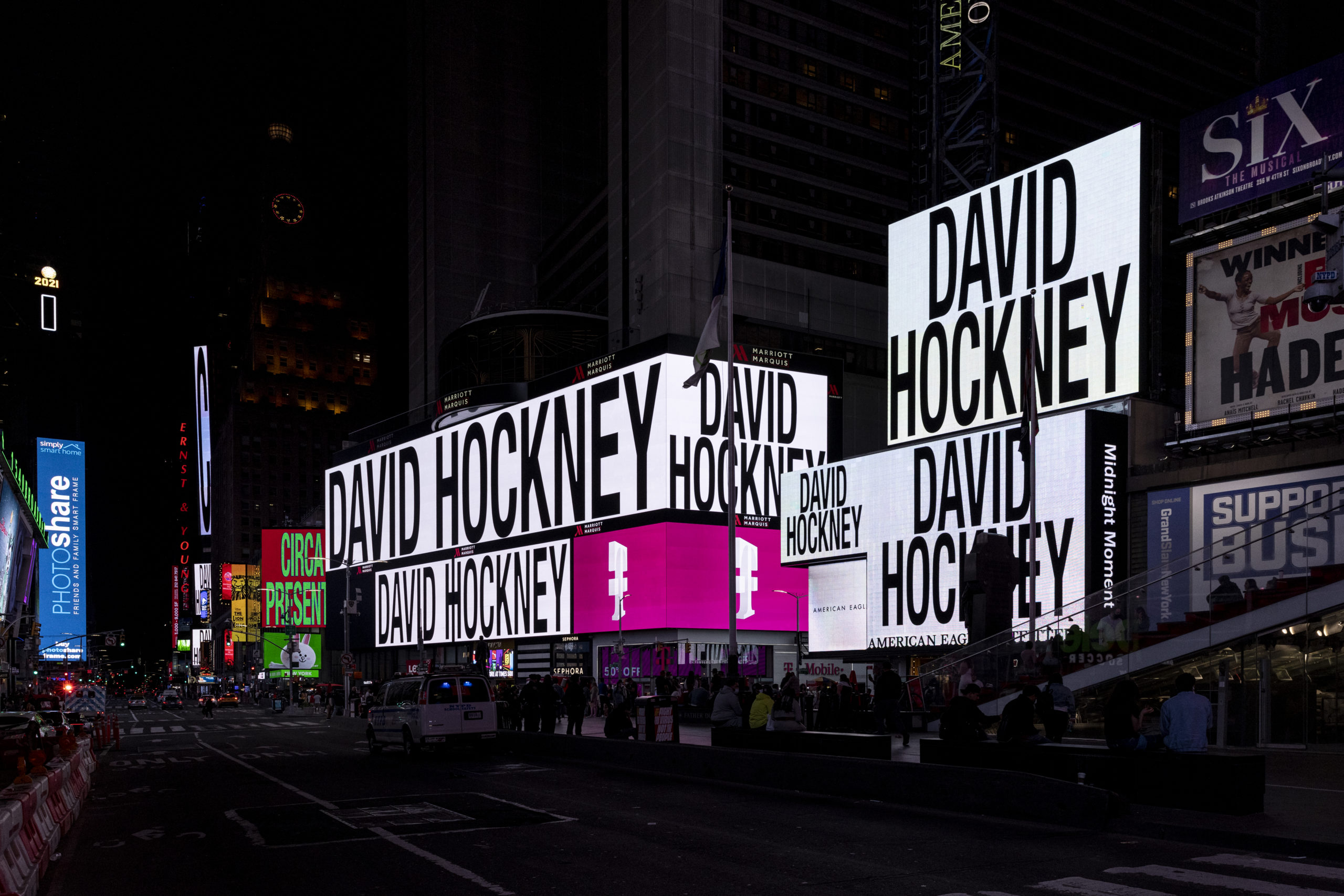

David Hockney’s new work for CIRCA will play for the month of May across the world on giant screens in London, Seoul, Tokyo, Los Angeles and New York. Spanning the full circumference of the globe, Hockney’s animated dawn will follow real dawn thirty-one times. Screened in the evenings, viewers will see the sun rise once again, not long after it dipped below the horizon. Coinciding in London with the opening of the Royal Academy’s new exhibition, David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020, the project further marks a moment of renewal for the country’s battered museums and the city’s dormant but fast rousing arts scene.

The video is short. Not quite ninety seconds for one loop. The motif is timeless and universal. Sun rose on the first day, it will rise on the last day. Sunrise shines throughout world religions, mythologies and cultures. An event inherently pregnant with a pluralistic resonance which belies the matter of fact solar dynamics at work. The earth spins on its axis for another time in the roughly four point five billion years of existence. Big whoop. Sunrise is simultaneously so utterly mundane and still, so powerfully magical. It ‘means’ nothing and yet, it can mean anything and everything to someone, somewhere.

Hockney is an avowed technician and art historian. Both his work and writing bear witness to a telescopic intellect which countenances the full breadth of (mainly Western) art history beginning with the very earliest marks on cave walls. In cave painting, contrarily, an absence of sunlight informed compositions. Herds of bison dance in charcoal and ochre across craggy surfaces once animated by flickering firelight. At Stonehenge the rising sun activated the monument at defining moments in the Neolithic consciousness. The motif of sunrise becomes especially prominent in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Impression, Sunrise (1872), Monet’s defining canvas, depicts a heavy lidded sun rising listlessly above a languid morning horizon. Mist and haze dissolve form and line into effervescent brushstrokes. For Turner, sunrise was license for an explosion of soft golden light diffused across Romantic landscapes. And for their Japanese contemporaries Hiroshige and Hokusai, both making widely disseminated woodblock prints, dawn offered a moment of dramatic mise-en-scène for favoured subjects.

In the 1600s, the age of Enlightenment and the dawn of science in Europe, light remained the ne plus ultra of religious epiphany. But for Baroque painter Claude Lorraine, sunrise enshrined a particular strand of pastoral, Arcadian utopia. Humanity at one with nature in a perfectly ordered world. It was not long before, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, that rays of sun were still innately divine. God’s perfect light shining on his perfect creation.

Hockney’s installation at Piccadilly Circus is not the first of Circa’s projects at the site. But one can’t help feel it’s the most eloquent alignment of form and content. Known as the Piccadilly Lights, the artificial glow of advertisements has been at the very centre of London’s urban experience since bulbs illuminated the first Perrier bottle in radiant modernity more than a century ago. Seen through the eyes of the Futurists, a group of Italian artists ferociously enamoured with the speed, efficiency and sheer luminosity of the pre-WWI age, the Piccadilly Lights in 1908 must have seemed the very definition of a modern utopia. To be like “Piccadilly Circus” still conjures visions of traffic, noise, bustle, crowds and commerce: life. Like the Great War, which so abruptly turned the Futurist prophecy of a bright new world into a living nightmare, the pandemic upended contemporary society, globally, almost overnight. Piccadilly Circus itself is a poignant and pointed location for a site of reflection on the current historical moment. Once again in the face of mass disease, like the Great Plague of London in the 1660s, one of the busiest cities in the world fell eerily silent.

Importantly, this project will be screened across the world, not just Piccadilly. Each screen in an iconic location loaded with historic sentiment and memory. There are few experiences which can, justifiably, be described as ‘global’. However the pandemic is one of them. It may come, in time, to be seen as the defining global experience and, contrarily, to have driven a new localism in response to the runaway tide of globalisation felt so keenly in recent decades. Each country, to some extent, has followed its own narrative during the pandemic, with relative triumphs or tragedies waxing and waning in tandem. As one country feels the warmth of spring and a blessed reprieve, another feels the icy chill of ‘excessive’ mortality. The Global North is, by and large, emerging from the pandemic, stepping out, blinking into the spring sunlight with renewed confidence for the future. But the Global South, contrastingly, still reels. India alone, which accounts for nearly a full fifth of the world’s population, is in the midst of an apocalypse.

With nearly eight billion perspectives on the pandemic, and a kaleidoscopic cacophony of individual experiences, there are few symbols imbued with ubiquity sufficient to speak in a meaningful way to recent developments. Sunrise is one of them. Almost every religion, creed or world view encompasses some form of sun deity or spirit. The potency of the rising sun cuts through aeons of human history. Whether in deliverance from cold, hunger, danger, fear, dawn brings a new beginning. A chance for redemption. As a cultural trope this borders on kitsch and cliché. Is it too vague and all-encompassing to really mean anything?

Art historically, kitsch – formulaic, shallow, repetitious and every day – took a beating at the hands of notorious art critic Clement Greenberg in 1939. Derided as cheap, folkish and proletarian, a rejection of ‘low culture’ and the celebration of ‘high culture’ was defined most succinctly as Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s and early 1950s. Hockney and Warhol (among others) turned this position on its head in the 1960s. Nascent popular culture, consumerism, advertising, this was the real language of the people. Not an esoteric, insular and elitist dialogue concerned with ‘expression’ through a mysterious process of instinctive abstract mark making. But daily lived experience, with all of its prosaic and trivial preoccupations, was to be the currency of Pop Art.

So the rising sun as trope is kitsch. It can indeed be loaded with Hollywood schmaltz, sentimentality and grandiose narrative puff. Kitsch and universality here become one and the same. Dawn, sunrise works as an emblem for the current moment precisely for this reason. It can be a monument to hope and the potential for rebirth, shining across borders.

In movies dawn is ripe with narrative. Science fiction in particular. In recent days gone by I’ve often thought of a favourite line from a favourite film:

“So if you wake up one morning and it’s a particularly beautiful day, you’ll know we made it”.

Spoken by Cillian Murphy’s character in Danny Boyle’s epic, cosmic and imperfect cinematic masterpiece Sunshine(2007), written by Alex Garland, these words seem so apt and appropriate for now. Although remote from our current situation, the film still speaks of salvation through technology. Premised on the notion that our sun is dying, a team of scientists are dispatched with a vast nuclear device to restart the ailing star. Perhaps a little farfetched, but eminently poetic. Life on earth, doomed to oblivion without the sun, is redeemed in the final scene by a sweeping new dawn bringing warmth and light to a snow mantled Australia. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) opens with an iconic sunrise to the strains of Strauss’ pounding Thus Spake Zarathustra (1896). Both films are paeans to the power of science and technology. In the most blinding and eloquent segue, a weaponised bone thrown skyward by a dominant ape becomes a spacefaring vessel waltzing elegantly in orbit above the Earth.

For all the failed apps, the misspent billions on government initiatives and all the failures of political leadership, the renewal of this particular spring and the possibility for rebirth is a miraculous product of modern science and technology. Vaccination programmes are underway around the world. The road is long and the journey far from over. While some countries enjoy enviable levels of protection, others stand naked against the virus. But, crucially, we can see a route out of global paralysis. Last spring, in 2020, Hockney reminded us all that spring could not be cancelled. Comforting at the time, the hope it offered was premature. This time we might, cautiously, timidly, hope it’s different.

So, we all live in a world full of hope after the darkest night, yes, but so too, a world still so full of death and suffering. The work’s title is a laconic rejoinder. The cycle of death, rebirth and renewal is a constant. Think on this, and get busy living while you can.

Henry Little is an art advisor with The Fine Art Group, a company supporting collectors at every level of the art market. Prior to that, he co-founded a commercial gallery in London, Breese Little, and worked at the Contemporary Art Society. He’s contributed to numerous Phaidon publications and continues to lecture regularly for the Sotheby’s Institute of Art. Henry and his wife Lucinda collect contemporary art with a focus on works on paper, editions and photographs by UK based artists. Henry studied art history at the University of Cambridge and the Courtauld Institute.