Douglas Gordon: How Why & What We Remember

Written by Louisa Buck

For more than three decades, Douglas Gordon has been making work that delves deep into the human experience and the functions – and dysfunctions – of memory, both individual and collective. Texts, music, films, signs, song lyrics and tattoos are just some of the means by which he has probed into how, why and what we remember – and explored the way our memories define our sense of who we are.

An early wall text, List of Names (1990), listed in multiple columns every person that the artist could remember meeting up to the year 1990, and the relationship of text to the limits of memory continued in a series of 1994 installations using the phrases, I cannot remember anything, I have forgotten everything, and I remember nothing. Each a different articulation of amnesia, the words appeared as fragmented and disjointed, scattered randomly and painted in different sizes across a pale blue wall.

The 1994 installation Something between my mouth and your ear gazed even deeper into the seemingly random but highly significant factors that may or may not have a profound effect on shaping our identities. The work filled a small blue-painted room with the sounds of a playlist of thirty pop songs all released between January and September 1966. This was the time of Gordon’s mother’s pregnancy, with the idea being that he might have heard these sounds in utero and thus been formed by them before his birth. However, Gordon’s chosen list of songs was a highly personal one. Rather than being based on a study of what his mother actually might have been listening to, it revealed more about the musical tastes of the adult artist. “There were some dreadful things in the charts during this time”, he recalled, “[so] I decided I had to be thoroughly subjective, which means goodbye to PJ Proby, Jim Reeves and Tom Jones, among others.”

The role of the moving image in shaping our imaginations and our recollections is also repeatedly explored, most notably in what is still probably Gordon’s most famous work, 24 Hour Psycho (1993), in which the Hitchcock classic is slowed down to last an entire day. Silently back-projected at two frames a second onto a suspended screen that can be walked around as well as viewed from both sides, the film that everyone thinks they know so well yields new and unexpected tensions, narratives and details. Such a radical re-presentation offers more than a clever dissection; it forces all of us to examine and reassess how we recall and understand these seemingly familiar images of obsession, voyeurism and suspense.

There’s more undermining of easy preconceptions in Gordon’s deceptively simple video installations A Divided Self 1 and A Divided Self 11 (1996), in which a pair of video monitors presents two arms, one hairy, the other smooth, fighting each other on a bed sheet. In the first film, the hairy arm has dominance, while in the second, it is the smooth arm that defeats its opponent. Soon it becomes clear that both sets of arms are the artist’s own and that the battle is between the two halves of his own self.

if, when, why, what Gordon’s new film commissioned by CIRCA for Piccadilly Lights marks another grapple with desire and its denial. It also makes direct reference to a very specific period in the artist’s life. When Gordon first came to London from his native Glasgow to study at the Slade School of Art in the late 1980’s he remembers wandering the streets of Soho, then the capital’s sex industry district of brothels and bars just a few blocks to the North West of both the Slade and Piccadilly Circus. Although enticed by the neon signs of the neighbourhood’s watering holes and strip clubs, he was too nervous to enter.

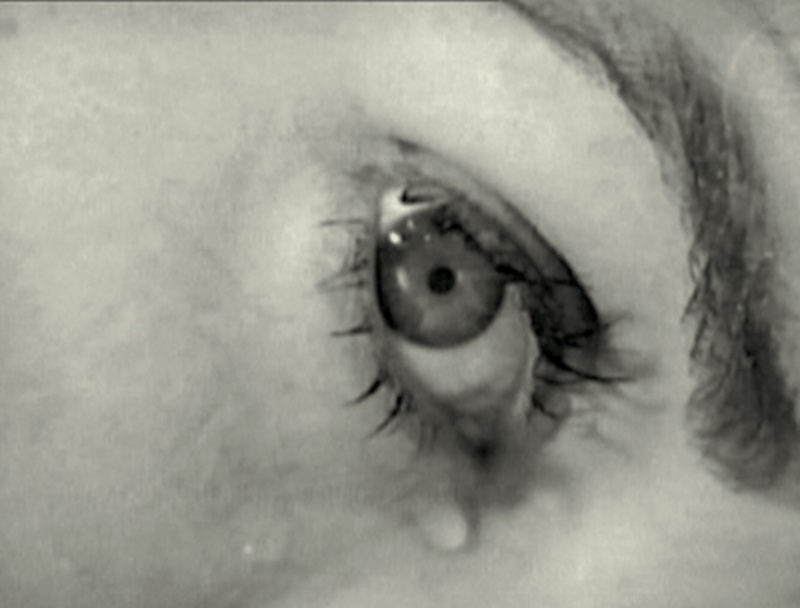

“I used to walk around that neighbourhood as a wee Scotsman only looking at things from the outside – because I was too nervous to go in”, he remembers. “Now [in this work], what makes it perfect for me is that I am revisiting something from my past – something I didn’t experience”, he explains. “I always wanted to see it – but I never got in – so the eye is my desire to look, look, look.”

It is this experience of the young boy from Scotland who was drawn to the forbidden fruit of what went on behind the closed doors of the city’s centre for bohemian bad behaviour that underpins his film work for Piccadilly Lights. The huge eye that blinks from the giant illuminated billboard is Gordon’s own, and the signs that are reflected on his retina are those of the many Soho establishments which no longer exist.

The fact that the names of these long-gone bars and strip clubs projected onto his eyeball are all in neon is also significant. Gordon has used neon in a number of previous text works, most notably Empire (1998), an illuminated green sign on permanent public display on New Wynd in Glasgow. This is taken directly from the neon Empire Hotel sign in Hitchcock’s 1958 movie Vertigo, but in Gordon’s version, the letters are reversed, with Empire only presented the right way round when reflected in a set of adjacent steel panels. Truth, reality, film noir nostalgia, not to mention the grim associations of the word Empire – especially in its location of Merchant City, an area of Glasgow built on the profits of colonial trade and slavery – are all conjured up in this single neon word.

On a more basic level, Gordon is also beguiled by the physical nature and effects of neon, a form of lighting made from the tenth noble gas in the periodic table. “Some words simply look better in neon”, he observes, adding that “ because it’s a gas and because it was discovered, not invented, it quickly became a byword or symbol for the very essence of discovery. ” This seductive sense of discovery conjured up in the glow of neon certainly made a strong impression on the young art student, new to the lure of London. “Discovered in London by a Glaswegian at the turn of the twentieth century, it seemed natural for me to fall in love with neon – first seeing signs in black and white movies and then later the real thing, in Soho, on Dean Street, Old Compton Street and Piccadilly Circus,” Gordon recalls. “The thin glass tubes, buzzing with the new vibrant element inside, beckoned you to come in, don’t be shy, take a chance, accept a dare and tell -or don’t tell – your friends.”

Now, as it blinks every evening at 20:22 local time across Piccadilly Lights – and beams around the world in New York Times Square, Berlin, Milan, Seoul and Melbourne during the festive season – Gordon’s work has also become a beguiling siren sign in its own right.

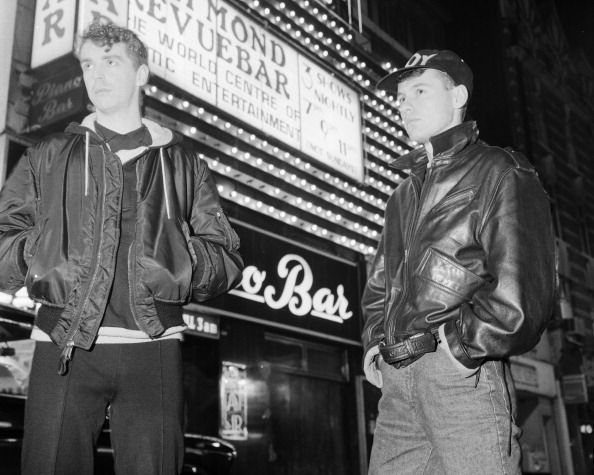

But at the same time as if, when, why, what is a global work, the title of Gordon’s CIRCA commission is a constant reminder that it is also rooted in a very particular time and place. The phrase is taken from the lyrics of West End Girls, the Pet Shop Boys 1984 synth-pop hit that has now become a classic anthem of mid-eighties London. “Too many shadows, whispering voices/ Faces on posters, too many choices/ If, when, why, what? How much have you got?/ Have you got it, do you get it/ If so, how often?/ Which do you choose/ A hard or soft option?” intones Neil Tenant in the official video for the song as he strides out against a London backdrop of teeming crowds and harsh street lamps. Not only do his words conjure up the enticing, bamboozling lure of London’s West End, as experienced by the young Douglas Gordon nearly four decades ago, but they also still stand as a barbed description of London’s nearby retail mecca of Oxford, Bond and Regent Streets.

Today Soho is almost changed beyond recognition, with many of its buildings and businesses vanished or redeveloped, victim to the homogenizing effects of gentrification and rising rents and all hastened by the construction of the Elizabeth Line. But Douglas Gordon is adamant that if, when, why, what is less an exercise in nostalgia and more what he describes as a “DNA profile” of the streets to the North of Piccadilly. “It’s an essential part of my memory, and I hope it will make people reflect on where they are,” he says.

With this most visceral homage to his old stamping ground, which, as well as being a red light district, has also always been known for its cosmopolitan clubs, businesses and restaurants, the artist is also paying tribute to the multinational communities who -like him – carry memories of Soho as part of their personal histories. Let’s hope that those coming to London from other places will continue to have the freedom to do likewise in the future.

Louisa Buck is a British art critic and contemporary art correspondent for The Art Newspaper. She was a jurist for the 2005 Turner Prize. She is also an author or co-author of books on the contemporary art market.