Eddie Peake: 2020 Tesseract

Written by Adam Heardman

2020 Tesseract: Problems of Origins With Eddie Peake

…then proceed through the green screen as a conduit or tesseract, a boundary where we synthesise endings in such a way as to go on, and begin.

[December 1st 2020]

When you first meet it, the phrase, A Dream of a Real Memory (which Eddie Peake has taken as the title for his series of films shot for CIRCA 2020) seems designed to send you hunting for its origin. Peake recently told The Art Newspaper that he was drawn to these words because of their “cohabiting of real and imagined thought”. His title enacts this cohabitation by corrupting its own beginnings. It’s adapted from a short story by the American writer, Wells Tower. An old man, who has just finished painting watercolours of the Mississippi sky, drifts off: “I fell

[December 2nd 2020]

asleep, and what I dreamed was a true memory”. Peake’s title is a deliberate misquote, a mis-memory, both real and imagined. As he says in the same interview, memory is “a kind of self-imposed lie”. And, if Peake’s title nudges at the fabric of remembered time, finding holes here and there, the films themselves almost entirely unravel it.

A Dream of a Real Memory comprises 31 films, each exactly 2 minutes long. Peake stresses that they are sequential, making up a coherent narrative, but they were shot and will be screened individually, one played each day of the year’s final

[December 3rd 2020]

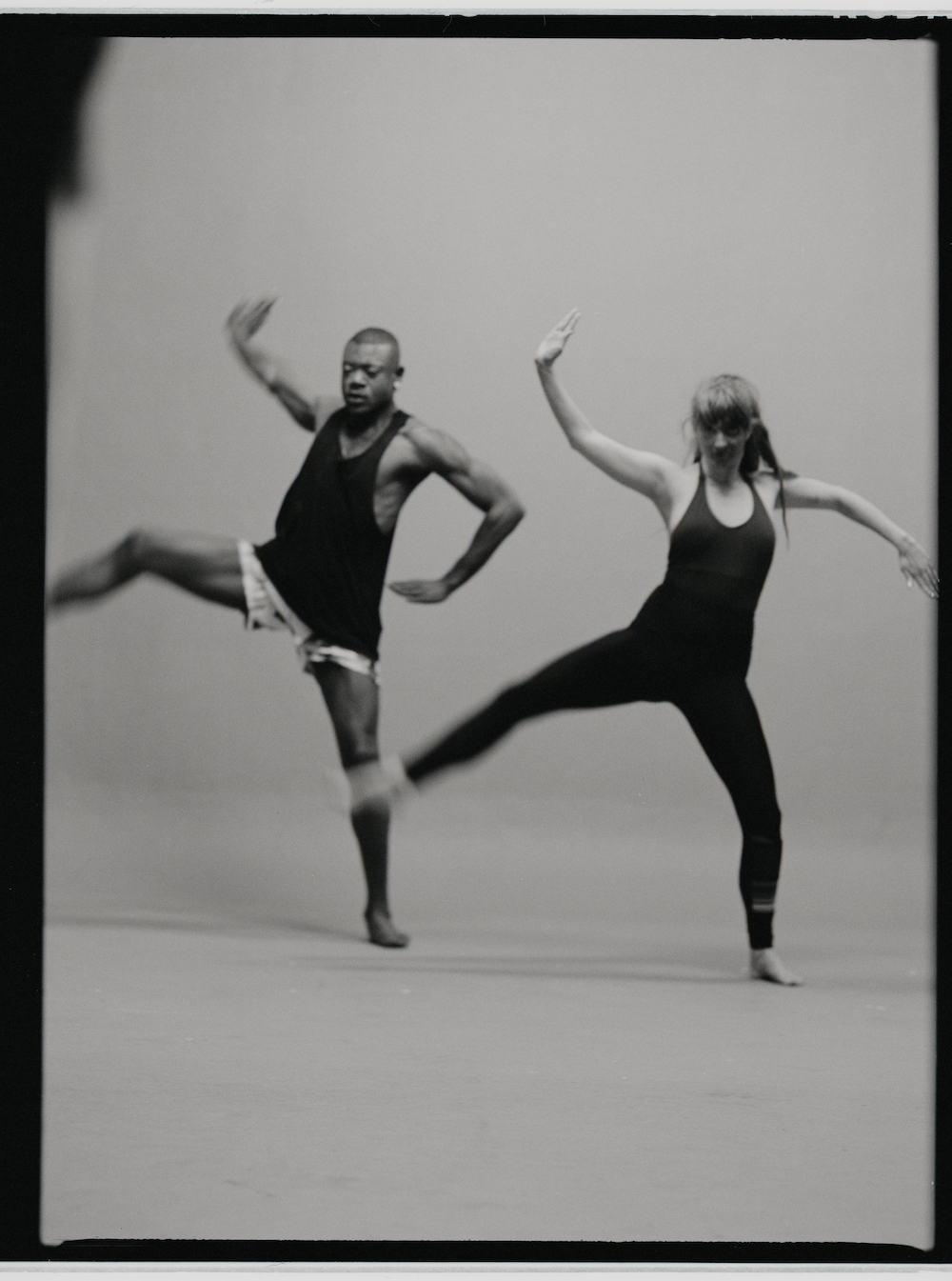

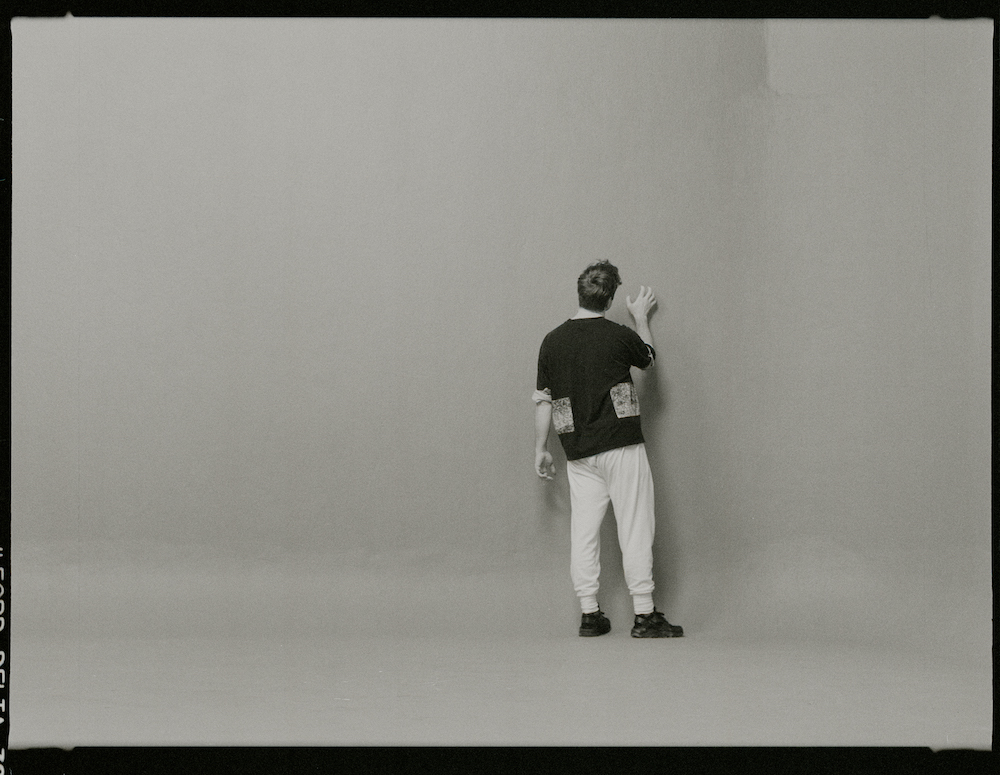

month on the Piccadilly Lights screens in Piccadilly Circus. In the films, two performers move and dance in dialogue with one another in front of a blank green screen. The films are played in reverse, so that the dancers’ actions are eerie and predetermined, and the sequence ends at its beginning. The performers wear face paint reminiscent of Japanese Noh theatre. The full 62-minute film is interrupted by the rigid ‘two minute episodes’ structure, and the dancers’ flow itself is interrupted by moments of laughter, conversation, improvisation, and, occasionally, by the filmmaker, Eddie Peake himself, also wearing face paint, entering

[December 4th 2020]

the frame with camera in hand, interacting with the dancers verbally and physically.

Just as the work’s title, A Dream of a Real Memory, encourages interpretation with its air of non-specific familiarity and intriguing openness, so the blank green screen seems to invite a viewer’s own projections and interpretations. Accepting this invitation, we’ll here attempt to unpack the films’ themes and concerns, and try to make some sense of their curious power, in a relatively open and associative way. And it makes sense to start with how Peake problematizes the idea of ‘origins’, explores and subverts what it means to

[December 5th 2020]

begin and what it means to continue. In a word, it makes sense to start with ‘time’.

A tesseract, or ‘hypercube’ is a cube in four dimensions. The tesseract is to a cube what a cube is to a square. For the purposes of this essay, though, we take tesseract to mean something like what the filmmaker Hollis Frampton means when he describes Eadweard Muybridge’s long-exposure photograph of a waterfall. Muybridge, famous for those sequential shots of a horse running, spent much of 1872 photographing Yosemite valley. At this time, he was working with collodion plate photography, a very slow

[December 6th 2020]

process with long exposure times. Anything which moved while the photo was being taken ended up looking blurry. In flourishing 19th century San Francisco, there was a great demand for photos of the Californian wilderness, and Muybridge’s contemporaries spent their time capturing the stillness and the vastness of Yosemite’s rocky landscape, or asking the indigenous peoples who lived in the valley to stand still for portraits. Muybridge, however, wanted to experiment, to push the new technology to its limits. He looked for the things out there which move. As Frampton points out, “he seems to positively seek, of all things,

[December 7th 2020]

waterfalls, long exposures of which produce images of a strange, ghostly substance that is in fact the tesseract of water: what is to be seen is not water itself but the virtual volume it occupies during the whole time interval of the exposure.”

Muybridge was perhaps the first to realise that all photographic art (and it’s clear that Muybridge did think of what he was doing as ‘art’) and, later, film (which he pretty much invented), disrupts and revolutionises our sense of how we experience time. He shot waterfalls because he knew they would expose our myth of time being

[December 8th 2020]

divisible or measurable as a succession of ‘moments’. A still photograph, or even the rapid succession of still photographs which make up a film, tries to give an illusion of time as something we can control, pause, and rebuild. As the word ‘waterfall’, a noun squashed into a verb, suggests, though, three dimensional things within the fourth dimension, time, are always already ‘going on’, are tesseracts of themselves, and our frames of reference are a kind of fiction that we impose upon the world. By dividing up his film across the final days of 2020, and by playing it in

[December 9th 2020]

reverse, Peake is, like Muybridge, pushing the rubric of filmmaking to its limits and exposing our perception of time as arbitrary. By challenging a photo or a film’s illusion of finite beginnings and endings, the two artists explore the aesthetic and ethical problems of origins.

Peake seems to also take cues from Muybridge’s more famous work, the sequences of photos of horses, humans, and other animals in motion. Muybridge’s project, Animal Locomotion, includes those iconic horse photos, but also studies of stylised human bodies performing gestures and steps like dancers. At some points, Eadweard, like Eddie, steps in front of

[December 10th 2020]

his own lens, creating a kind of self-portrait. Muybridge’s images of his naked, walking self are done, like all the photos in Animal Locomotion (and like Peake’s films), in front of a blank screen. Most portraits are interested in preserving the sitter, creating an image outside of time that will survive. Muybridge and Peake step into the frame differently, almost anonymously, joining in with the ongoing rush of time in a blank ‘any space’, themselves ‘any body whatsoever’, tesseracts of humans which we glimpse only briefly within our limited allotment of time. In a sense, this becomes an ethical concern.

[December 11th 2020]

The eking out and portioning of a person’s life into dates and hours has long become associated with labour, working hours imposed as a fundamental structure of control. The simple phrase ‘free time’ suggests some fundamental link between liberty and temporality – to gain time is to gain freedom – and the rise of hourly rates of pay and zero-hours contracts make it clear that workers are not paid for the true value of their labour; rather, they sell that most precious commodity-unit, time. Codifying the essentially arbitrary process of objectifying time into saleable components as a fundamental tenet of human existence

[December 12th 2020]

was one of twentieth century Capitalism’s greatest and most troubling victories. It’s difficult to imagine a life not patterned by hours, minutes, seconds. Art like Muybridge’s and Peake’s uses and exposes these patterns and helps us visualise time as the free continuum it actually is.

There’s also a more contemporary phenomenon associated with units of time which operates in a similarly oppressive way. In current Western, internet-inflected discourse, every year since at least 2016 has been branded by some or many people as “the worst year in history”. A proliferation of memes and tweets in response to everything from Trump

[December 13th 2020]

to Brexit to Europe’s refugee crisis to the deaths of celebrities captures a vibe that can be, and often is, summed up by the phrase “Fuck 2020”. This year, it’s common to see someone tweet something like, “Another fucking lockdown. Can’t wait for 2020 to end.” Though it’s an attempt to show solidarity and stoicism (hey, man, I know this situation is shit, but we’re all in it together and it will pass) this discourse flourishes (and is allowed to flourish) because it operates as a palliative not only to those suffering in such circumstances but also to those responsible.

[December 14th 2020]

The “Fuck 2020” discourse explicitly blames an arbitrary bracket of time for everything that goes wrong within it, as if the 365 days marking two-thousand-and-twenty years since the date when Jesus Christ may or may not have been born bears any fundamental relationship to the misfortunes and instances of deliberate malice which they contain. In shifting the blame for things like the coronavirus pandemic from those human beings and those oppressive systems which are actually responsible onto an arbitrary and nebulous concept like “2020”, this discourse encourages people to consider malicious geopolitical activity and random bad luck as equivalents. Look,

[December 15th 2020]

for example, at 2016, when tweets mourning David Bowie, or any of the public figures who also died that year, were expressed in exactly the same tone and language as tweets about the result of a Brexit vote engineered by deliberate actors with aspirations of power and profit. Time units have been used in two ways as tools of control: first, by objectifying and commodifying them as tradable things and, second, by sort of personifying them as agents of blame. Any new form of discourse which hopes to enact a meaningful resistance might direct itself against this unit-based commodification and

[December 16th 2020]

personification of time. Peake’s films, by occupying and then deconstructing time measurements, dissolving frames back into a continuum – at the very end of a year, and a decade, defined by rising fascism, government mismanagement of crises, and more – reminds us that these problems won’t simply end at midnight on December 31st. Resistance is a continuous act and a revolution isn’t linear.

Peake’s films certainly aren’t explicitly political. Their two-minute slot each day will, like all the works in the CIRCA 2020 project, interrupt Piccadilly Lights’ otherwise constant stream of logos and adverts, which is itself a radical act of anti-Capitalist

[December 17th 2020]

disruption, but the content of the work is certainly not as overtly politicised as its CIRCA 2020 predecessor, Cauleen Smith’s extraordinarily powerful COVID MANIFESTO, which ran throughout November. This being said, it’s hard not to read Peake’s videos within the context of a debate which has come to rage around contemporary, conceptual art and thought in what has come to be known as the “post-truth” era.

A Dream of a Real Memory is predicated on the corruption of ‘truth’ by memory. As we’ve seen, the title deliberately dispenses with the word ‘true’ from the original quote that it adapts. The

[December 18th 2020]

films themselves are challenging, conceptual, weird. The filmmaker enters the frame and you see his camera. The “actors” break “character”, and the whole thing seems to deconstruct itself, showing its processes. It could be argued that, in taking place in front of a green screen that is yet to have a CGI background projected onto it in post-production (as green screens normally do) the entire film itself exists ‘as process’, in a zone of endless and endlessly unrealised potential, ‘any space whatever’ and also decidedly ‘no-space’. Because of these facts, and because they will be broadcast in such a high-profile

[December 19th 2020]

public space, the films unavoidably enter into a broad and crucial contemporary debate about art, language, politics, and “truth”.

One way of beginning to understand this debate is by looking briefly at one of its focal points: the legacy of the French-Algerian philosopher, Jacques Derrida. To paraphrase briefly (and hopefully not too reductively), Derrida, from the 1960s until just after the dawn of the new millennium, set about deconstructing some of the fundamental, received notions upon which all Western philosophy was built. For Derrida, it was a problem of ‘origin’.

The problem with origins is that they end up privileging

[December 20th 2020]

something, becoming a system of power. Western philosophical thought got very comfortable with Plato’s idea that our ‘perception’ of the world was secondary to ‘reality’, that when we saw or thought about something, it was the ‘something’ that was more ‘real’ than the thought. Reality/thought then becomes a binary opposition with one term privileged over the other. This teleology was responsible for the idea of a Golden Age at some unspecified point in the past from which we have fallen (consider Eden), and that our lived experience is one of deterioration, or, at least, further departure from God or

[December 21st 2020]

Truth.

And, to paraphrase in a way that’s definitely too brief and reductive, Western philosophy relied on observing these strict binaries, from Plato to Aristotle to Descartes to Hegel to the Nazi Heidegger. Derrida interrupted this sequence with his idea of ‘différance’, suggesting that stuff exists just because it’s different from other stuff. Nothing ‘came first’. The sequencing of things, the idea of privileged binaries, even the construction of ‘time’ itself, is a fallacious human projection from an impossible or imagined standpoint outside of time.

Derrida’s implied idea that there’s no objective original ‘truth’ behind our perceptions of the world

[December 22nd 2020]

was hugely influential in post-modern discourse from philosophy to literature to art, but also made him a lot of enemies. And, in his excellent new biography of the philosopher, Peter Salmon diagnoses a contemporary strain of anti-Derridean criticism. He identifies commentators on the ‘post-truth’ age such as Michael D’Ancona and Michiko Kakutani, the latter of whom, in his 2017 book, The Death of Truth, “blames ‘academics promoting the gospel of postmodernism’ for the rise of Donald Trump.”

Derrida’s philosophy – or, more accurately, certain schools of thought and literature that it influenced – is currently being seen as giving license to a

[December 23rd 2020]

political arena in which anyone can say anything without recourse to social or academic authority. This space is easily co-opted by reactionaries, and power rests with whoever speaks loudest, longest, least-coherently.

It’s a compelling case, and one which is pertinent to the contemporary creative arts and their postmodern inheritance. What, for example, becomes of poets influenced by 20th and 21st century writers like John Ashbery, for whom deconstructing the historically-oppressive architecture of the English language into something abstract and expressive was a radical act of creation, but whose freely-associative, percussive, furiously allusive poesy now risks sounding like Trumpspeak? What needs

[December 24th 2020]

to be considered by a filmmaker like Eddie Peake when he slickly and decidedly takes apart the systems of narrative filmmaking, anatomises ‘dance’, and picks apart ‘time’? Though Peake is keen to stress that his latest work doesn’t explicitly contain “any reference to our current state”, the ways in which he overcomes the type of criticism that D’Ancona and Kakutani level against Derrida’s followers is quintessential 2020: he does it by reconsidering ‘screens’ as, rather than ‘barriers’, something more like ‘conduits’. In the age of video-chat Christmases and normalised paradoxes like “social distance”, Peake explores how meeting and penetrating various

[December 25th 2020]

‘screens’ performs an erotics and an ethics of contact.

To unpack this, it’s important to acknowledge something hitherto unmentioned. These films are very sexy. Peake is unabashedly interested in making art that is erotic. In the December 16th video, one performer flexes and flows through Olympian, gladiatorial poses while the other lies, odalisque and poised, at the room’s centre. Elsewhere they contort their bodies into seductive forms, licensing their own roving hands, getting a feel for themselves. As they caress themselves and each other, the roving handheld camera performs its own erotic motions, its own kind of optic caress, straddling

[December 26th 2020]

boundaries, stepping over lines. This is Eddie Peake, remember, an artist probably best-known for staging a nude football match in Burlington Gardens.

But the erotics of the film relies on a dialogue between moments of stylised tension, arched backs and twisting throats, offset with those moments of release when the performers laugh, joke, and break the fourth wall. In one of these moments, as mentioned, Peake himself walks into the set. The dancers stroke his face. He has stepped through the screen and made contact, but this contact would mean far less if he hadn’t had to overcome a boundary

[December 27th 2020]

to achieve it. It’s participatory rather than objectifying. Again, the film’s title signals the importance of this kind of jouissance, this erotics of deconstruction. It is taken (remember?) from a short story by Wells Tower. His protagonist, an elderly wheelchair-user who is rediscovering his latent sex drive, falls asleep and dreams of a “true memory”. In this dream of a real memory, he’s kissing a former sweetheart on top of a grave. Leaning against a screen which separates the living from the dead, two mouths meet in an embrace. The sexiness of it is compounded by its proximity to death.

[December 28th 2020]

The erotics relies again on slipping across divides like living/dead, waking/sleeping. It also relies on the cheeky art of collapsing the boundary between “real and imagined thought” which Peake notes (the ‘true memory’ belongs to a fictional character). Tower’s text, like Peake’s films, reaches in two directions, in and out, overcoming the spaces between two subjectivities in an act of erotic union. Wells Tower – whose own name evokes this sense of reaching out in two directions, deep into the earth like a well, up to the sky like a tower, as the dancers will do in Peake’s December

[December 29th 2020]

15th film, bodies bent forward with arms outstretched, then turned to one side so the hands point up, down – knows that meeting then overcoming a boundary is an important act of resistance to structure, a dissolve around a fissure, a contact with An Other who was divided from you by some system. Eddie Peake (whose own name invites similar close-reading: eddies in streams are points of reflux where the flow regresses in whorls. This happens in, among other places, river channels and the space-time continuum. The relationship between ‘Peake’ and ‘Tower’ is clear) knows this, too.

After making this up-down

[December 30th 2020]

gesture on Dec 15th, the dancers will barrel-roll and look the other way, the opposite arms reaching down like a grave, up like a headstone. The movements of the two performers seem always to be built around this grammar of mirroring, combining point with counterpoint, straddling some boundary like a mirror/screen.

On December 1st, 2020, I will cycle to Piccadilly Square. I’ll leave only just enough time to get there for 20:20, and will have to rush to make it. I’ll watch Eddie’s opening (closing) film. The soundtrack is the world. Will I do this every day until

[December 31st 2020]

December 31st, 2020? On this last, first day, the dancers laugh, stretch, warm-up, preparing for what’s to come and has already happened.

At which point nothing remains but for me to stride into the room. I ask Eddie for directions, salute the beautiful bodies, make sure to go the opposite way to which I’m pointed, and slip between two frames, rounding an impossibly thin corner in the glance of two worlds, then proceed…

Works Cited

Wells Tower, Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned (Granta, 2009)

Louisa Buck ‘Circa: Art for Our Times in Piccadilly Circus’, The Art Newspaper (No. 329, December 2020)

Peter Salmon, An Event, Perhaps: A Biography of Jacques Derrida (Verso, 2020)

Hollis Frampton ‘Fragments of a Tesseract’ (1973) in On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters: The Writings of Hollis Frampton (MIT, 2015)

Adam Heardman is a writer and poet from Newcastle upon Tyne. He writes reviews and features on art for Art Monthly and has previously written for Frieze, Tribune, The Independent, and more. His poems have been featured in PN Review, Belleville Park Pages, eyot and elsewhere, and have been included in gallery shows at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art and Berwick Visual Arts.