Ai Weiwei: Animality

Written by Stephanie Gavana

I’m thinking about animals, about Ai Weiwei and his cats. I’m thinking of the 40 feline creatures that populate his Beijing compound, how it must feel to have your daily life surveilled by 80 prying eyes. In doing so I’m reminded of another cat, Logos, the siamese pet of Jacques Derrida, and the now famous encounter that took place between them. When emerging from the shower one morning, Derrida found himself disarmed by the fixed gaze of the cat upon his body. Caught off guard, not only by Logos the cat, but by the unexpected shame of his nudity before this animal who looks on ‘just to see’.1 What is it to be seen by one’s cat, or by any animal? Encounters like these disturb our complacency about what it is to be human, they invite us to consider not so much what we know about animals, but what they force us to acknowledge about ourselves, that which we ignore. When the animal looks back, we are exposed. In its bottomless gaze; a call, a cry, a plea for a response.

Presenting scenes of mass commercial livestock farming, slaughterhouses, religious ritual and environmental destruction, Ai Weiwei’s ANIMALITY is a stark portrait of human-animal relations in the present. Camels are paraded through a frenzied crowd, bucking as they’re beaten with sticks from either side, their evident distress matched not with compassion, but with violent eruption, the carnivalesque overspill of the human appetite for domination. We bear witness to ‘what happens to the fraternity of brothers when an animal enters the scene.’2 Expelled, their mouths are bound with rope as they’re herded onto a lorry. Actions that insist Do not look. Do not respond.

The human capacity for cruelty is long documented, and no being has borne the brunt of that suffering longer than the animal. Blood covers the ground of a ritual ceremony, a thick red carpet furnished with the headless carcasses of goats. One dismembered head is wrapped in ribbon, a gift, offered to the gods upon a burning mound. In his discussion on ‘Eating Well’3 Derrida notes that all cultures are organized around a notion of sacrifice that provides a space for the ‘non-criminal putting to death’ of the animal. The act of killing in ritual contexts binds the collective through guilt, while identification rests on the act of consumption, the shared meal. This carnivorism is reflected everywhere in contemporary relations. Whether sacrificed or regulated, animals are killed and exchanged so that human society is possible. Binding us together through the flesh and blood of their bodies, they reassure us of what we are not.

Weiwei’s footage of caged animals is haunting. Dogs, Tigers, Lions, Bears. The spectre of the animal shapes not only how we respond to non human beings but stews at the core of our justice and legal systems to perpetuate an exclusionary juridical logic. Who possesses the right to live, and under what circumstances? In these systems, Animals are the absent referents,4 the nameless and invisible bodies that must be excluded for politics to exist. Despite the ethical choices we may make as individuals, a framework of structural carnivorism demands that on some level we accept the violence committed against non-subjects, especially animals. We all have skin in the game. And like thieves in the night, it is the abstraction of violence inherent in these systems that serve to neutralize and sustain it. When the animal looks upon us, we long to look away.

ANIMALITY clarifies, it holds up a mirror to the suffering we subject animals to, and by extension, all others deemed non human. A pack of undead dogs are resigned to a half-life beyond the bars, their spare and sorry frames litter the floor of their enclosure. One looks out – the dark abyss of its eyes speaks of knowing. Cut to a table of canine flesh, skinned and stiff, muscle and bone. The hacksaw lands and the feast ensues. The economy of meat. In Totem and Taboo, Freud notes that in some rites, the guilt-ridden instrument with which the killing was done was banished to the sea.5 And as the lazy Susan slowly turns, there is not a knife in sight.

The animal body is of course not the only property that is claimed in the human pursuit of conquest. Their habitats, too, bodies of land that we short-sightedly exploit. In ‘The Second Body’, Daisy Hidyard proposes that every living being has two bodies; the physical flesh-and-bone, the body which eats and sleeps, and the second body, an uncanny global presence that encompasses our environmental impacts. Through a desolate flood-scape, the brittle branches of remaining trees are mirrored by shots of small dying birds. Their twig-like claws, little forks, caught in nets of nylon and polyester. We spin the most careless of webs. The camera, a surrogate second body, taking notes as it hovers over our destruction. Cause, effect, cause, effect.

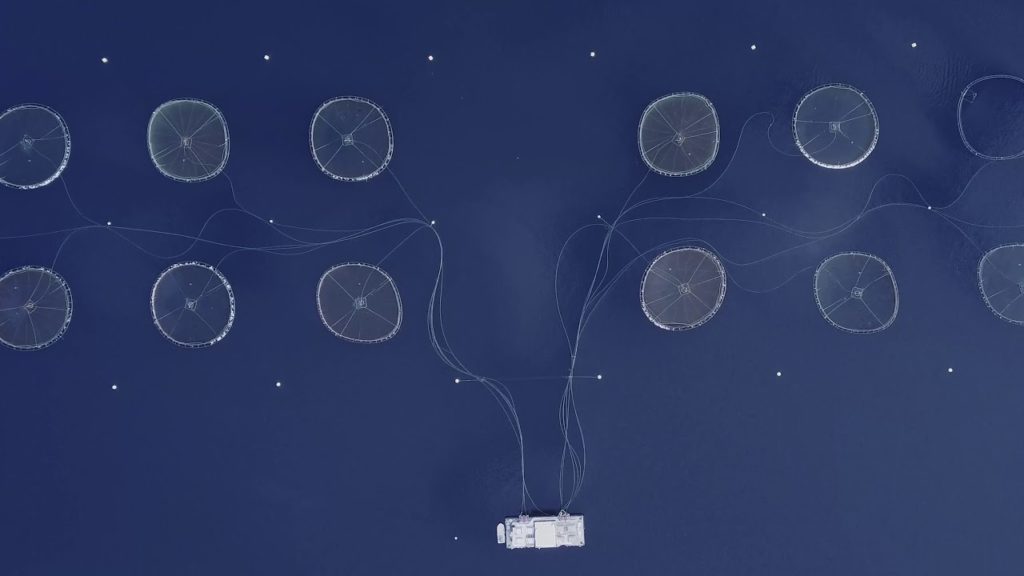

As the film progresses, so too does the abstraction of violence. Cosmic ripples of sound conspire with imagery of industrial fish farms to present something beautiful and alien; seemingly innocent blue lemons that bob on the surface of our oceans. The sound distills to a mechanical chime as we’re transported to the killing floors, the factory line of the animal-commodity. An ongoing procession of stunning, exsanguination, skinning, scalding, dehiring, evisceration, splitting. The repetition is numbing. In the final scene an industrial structure is adorned by waves of animal flesh, tidal in its enormity. I struggle to identify what these beings once may have looked like. All I see is roses, pink and blooming. This is what allows humans to hide from and disavow suffering. It is the vehicle of violence and the mechanism that enables us to distance ourselves from it. It is the veil that prevents us from looking.

ANIMALITY shows up-close the ways in which humans imprison themselves and others in relations of suffering. ‘This is the animal’s world; they are willing to live with us’ writes Weiwei, but are we willing to live with ourselves? Perhaps it is only when we relinquish the idea of animals as objects, brutes or property that we can begin to foster a human kinship based on dignity and difference. ‘The animal looks at us and we are naked before it’, Derrida notes, ‘Thinking perhaps begins there’.6 The animal walks on, all seeing, across the terrain that binds us; hooved, horned, winged, gilled. A swollen expanse that howls to be closed. Look, I am here. Respond.

1 Derrida, Jacques. 2002. The animal that therefore I am (more to follow). Translated by David Wills. Critical inquiry (28).

2 Ibid, p.381.

3 Cadava, E., Connor, P. and Nancy, J.-L. (1991). Who comes after the subject? New York: Routledge, pp.96–119.

4 Adams, C.J. (2019). The sexual politics of meat : a feminist-vegetarian critical theory. New York ; London Bloomsbury, p.14

5 Sigmund Freud and Strachey, J. (2001). Totem and taboo : some points of agreement between the mental lives of savages and neurotics. London ; New York: Routledge, p.159

6 Derrida, Jacques. 2002. The animal that therefore I am (more to follow). Translated by David Wills. Critical inquiry (28). P. 397.

Stephanie Gavana is a writer based in London.