Ai Weiwei Revisiting: Kui Hua Zi

Written by Louise Camu

It’s a grizzly overcast afternoon, and the pale October light filters through the narrow vertical windows at the end of the hall, lending the installation a solemn and melancholy air. As I approach, the homogenous grey carpet begins to take form; I move closer still.

The field runs the length of the hall like a giant sandpit, a carpet of intricate beads or pebbles. Upon reaching the edge, I kneel to pick up a small rounded object. Isolated in the palm of my hand, I realise it’s sunflower seed, one of a million and smooth to the touch, only slightly larger than my thumbnail in size.

Have you ever tasted one? Place it on your tongue and suck on the salty husk before biting down to break it open and free the nutty-tasting kernel at the heart of it. The outer shell is inedible but elegant and ornamental – like Greek decorations on ancient clay pots. But this one isn’t real. I rub the seed with my thumb and look up, perplexed.

The hall hums with activity as all ages interact. Across the field, kids are chasing each other, couples lie beside one another, people wander or lounge around and chat, and some look around…lost in thought. Ahead of me, a father struggles to convince his young toddler to spit out a porcelain husk. Walking out onto the grey expanse – in awe at the sheer scale of the work and the whole endeavour – I feel as though I am walking across a beach, with each step resounding like the satisfying crunch of shingle underfoot.

I sink down amongst the seeds and pass my hands over them, feeling them trickle through the gaps in my fingers. There’s a refined beauty in the simplicity of the work. No one seed the same; each unique brushstroke a stand against conformity. But here, the million individual pieces work as one.

Japanese rock gardens spring to mind, built-in temples or monasteries as sacred spaces for meditation and contemplation; the raked gravel meant to imitate ripples on the surface of the water. I, too, am floating on a vast monochrome sea, suspended in time and shrouded in mystery. I feel compelled to lie here, to ignore the rush and take a moment to contemplate this monument of Chinese craftsmanship. This field is imbued with significance. I can’t put my finger on it, but it feels complex and urgent, challenging and moving. I’m trying to understand it.

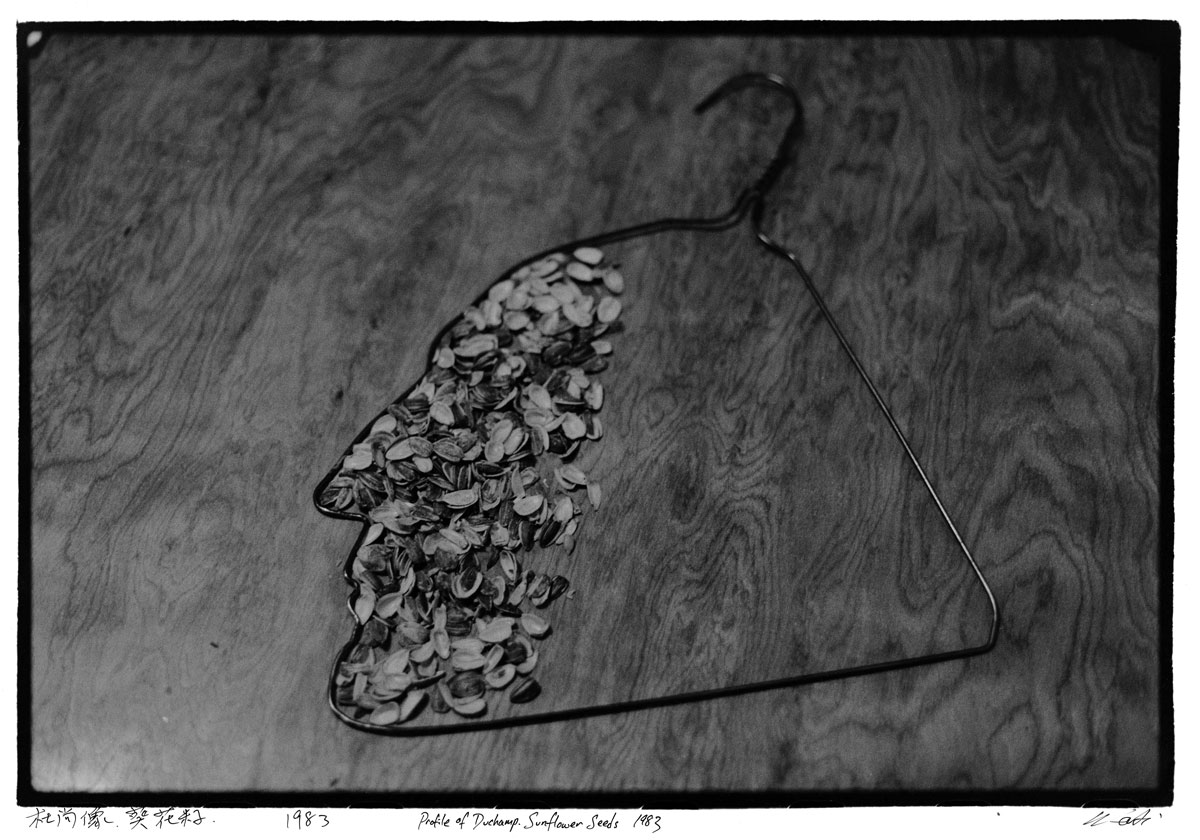

I’m looking at a photograph by Ai Weiwei, dated 1983, taken soon after his arrival in New York from Beijing. A wire hanger, bent into the elegant profile of the surrealist Marcel Duchamp, rests on a wooden surface partially filled with the discarded husks of real sunflower seeds.

In Ai’s work, sunflower seeds are a symbol of Chinese heritage and history. In times of struggle or celebration, the seeds were often shared amongst strangers and friends – they have been named the ‘seeds of freedom’ by activists in China. In ancient Greek myth, sunflowers carry connotations of admiration and loyalty, and in Maoist imagery, the seeds are reminiscent of the regime’s loyal subjects, with the former leader often represented as a radiating sun surrounded by sunflowers. To Ai, they are a radical “sign of social activity” and exchange between people.

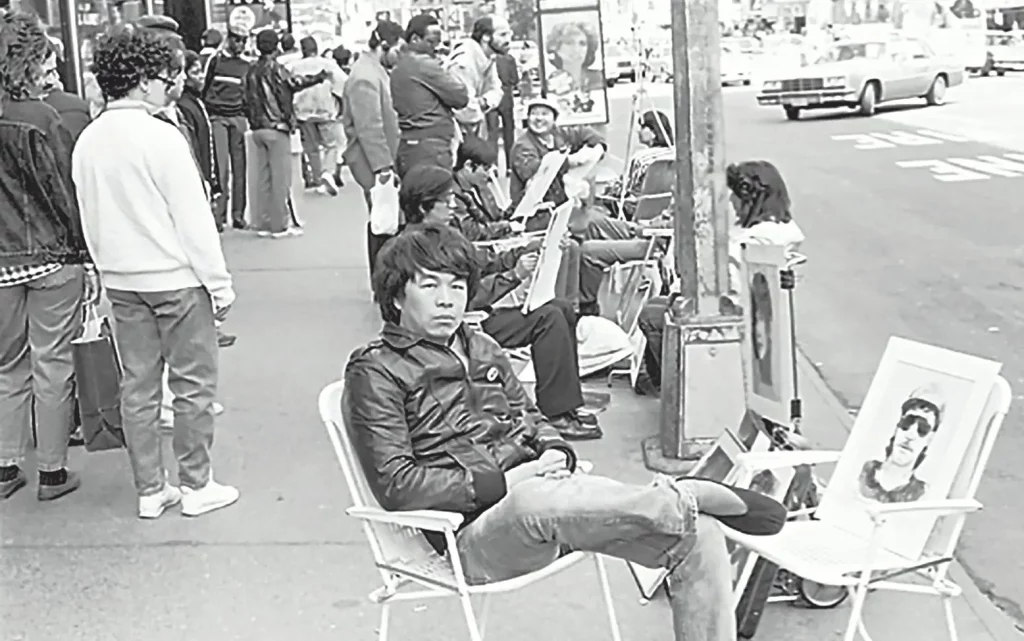

I first came across Hanging Man (1985), featured above, at the Ai Weiwei exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art in 2015. It is one of the first of Ai’s works to reference Duchamp and his notion of the ‘readymade’ – an everyday object recast as an art object by the artist. Duchamp was a pivotal figure in the development of Ai’s conceptual practice, introducing the artist to the subversive technique of re-appropriating materials and objects in order to alter both their value and significance to extreme ends. Over the following decades, Ai would expand the notion of the ‘readymade’ beyond its original definition, using it to extend his critique of the Chinese system. The seed had been planted. More than 25 years later, these elements would come together and resurface in Ai’s large-scale installation at the Tate Modern.

I watch as skilled hands sift through the porcelain seeds, and water is poured over them to wash away the remaining debris, dust and dirt. A statement from Ai appears in the centre of the screen:

“I have a Totalitarian regime. It is my readymade.”

In the context of the installation, Ai’s ‘readymade’ could be two things. First, the seed, as it transcends its function from everyday grub to cultural symbol and art object. Second, the Chinese totalitarian system transformed from a socio-political reality into a physical construct – fertile fodder for the artist. Here, the readymade takes on a more abstract quality. The statement is vague but compellingly so.

There are apparent antagonisms at play throughout the work, as the individual faces the collective, ancient Chinese practices negotiate with contemporary art, unique craftsmanship plays on mass production, and the monumental presence of the work grapples with the noticeable absence of each of its creators. Yet it’s the interstitial space between these that are of interest to the artist. By wedging himself in between, Ai makes room for a generative dialogue between opposing notions – a neutral space in which to operate and drive this politicised act of cultural exchange.

The power of the work ultimately rests in its accessibility and ambiguity, in the audience’s freedom to draw their own conclusions and interact with the work in whichever way they please. It continues to raise important questions about the role of public art as a platform to communicate urgent issues and subvert orthodox practices, to bring to light peripheral art practices and provide a vital contribution to both discourse and exchange.

Louise Camu is a writer and visual artist based in London. She is currently studying on the Royal College of Art’s Critical Writing MA