Agnes Denes: Wheatfield–A Confrontation And Its Monumental Legacy

Written by Barney Pau

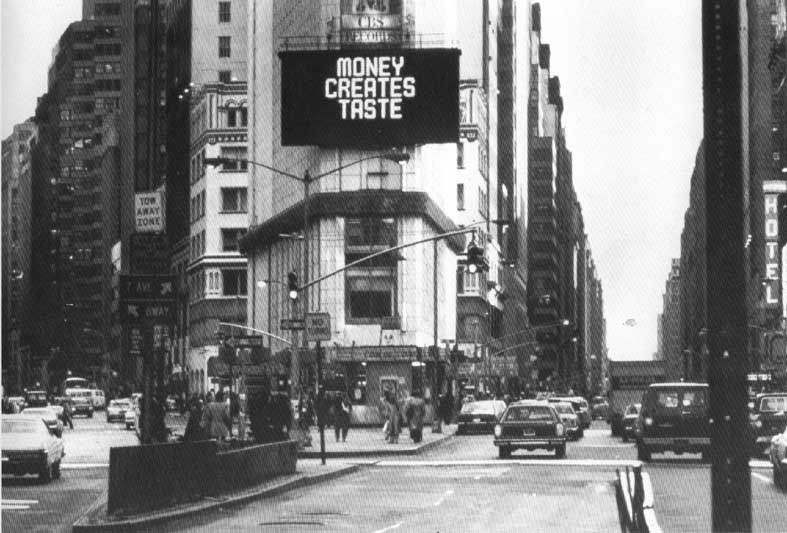

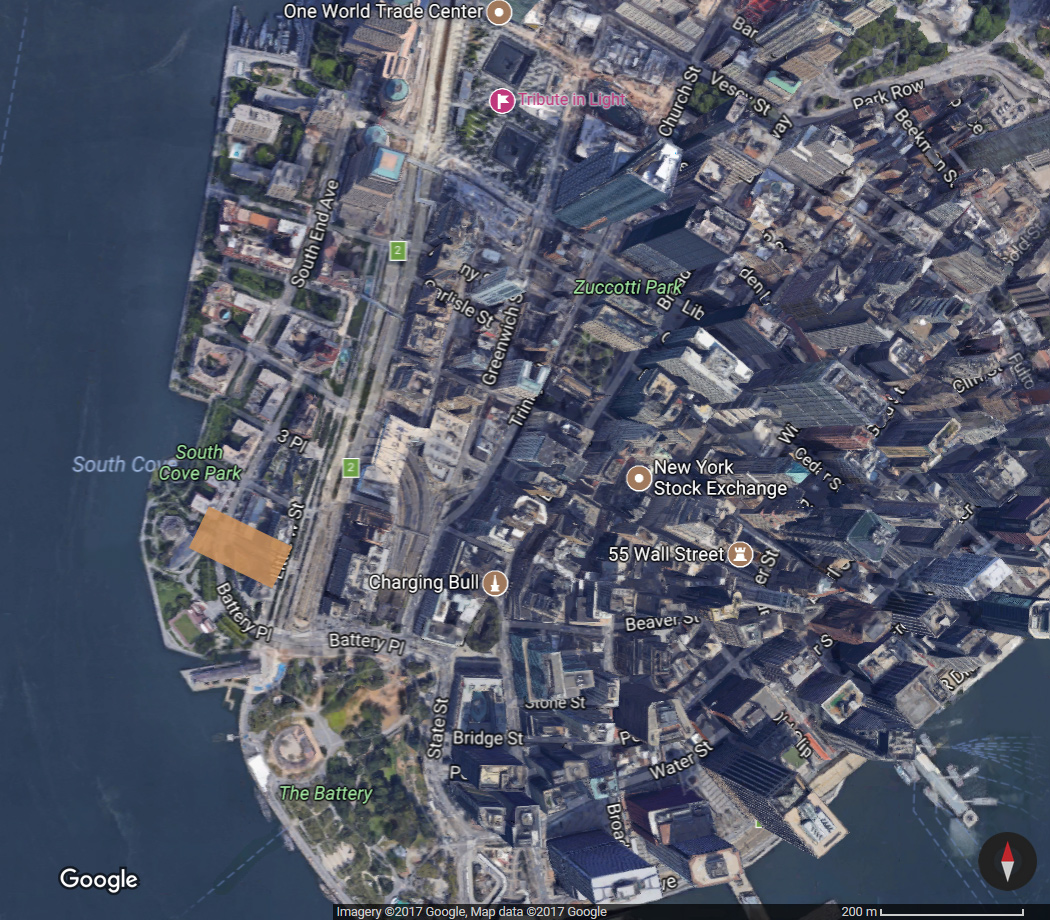

Despite the permanence of her practice—raising hills; planting woodland; burying time-capsules—Agnes Denes’s most enduring legacy might be her most ephemeral work: Wheatfield – A Confrontation (1982). The installation took place in New York’s downtown, in the shadow of a skyline synonymous with success. Such monumentalism is so immutably infallible that we cannot conceive of its demise. A shrine to hegemony; it represents the pinnacle of human progress. Yet, by planting an innocuous field of wheat at the feet of the World Trade Centre, Denes reminded us of the fragility upon which this world is built. The installation lasted a mere four months, from its planting in May to its harvest in August, yet its legacy still resonates four decades later.

Wheatfield was a call to action; in Denes’s words, an invitation for people to “rethink their priorities and realize that unless human values were reassessed, the quality of life, even life itself, was in danger” (agnesdenesstudio.com: n/d). At the time, the 2 acre plot on which the field was sown was valued at $4.5bn. This meant that, upon harvest, each wheat berry had the value of $351.56—the costliest grain ever grown. For comparison, on 16th August 1982—the day of harvest—the US market value of a bushel of wheat was $3.41; or 3 grains to a cent. Denes’s Wheatfield highlighted the vast disproportionality of human value systems; “[i]t called attention to our misplaced priorities” (agnesdenesstudio.com: 1982).

Wheatfield’s confrontation did not end with its’ harvest. Five years later the grain travelled the globe with the The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger (1987-90), where visitors were encouraged to take the grain and sow, as part of an international seed exchange. Since agriculture’s genesis, the seed commons has been sacrosanct. The seeds commons is the open-source interchange of seeds that has historically enabled growers to exchange and diversify their crops, interbreeding them to be better suited to their environment; a refinement process that has lasted over 12 millennia. During the 20th century mechanisation, artificial fertilisers, chemical pesticides, and plant breeding astronomically increased agricultural efficiency and yield. This came to be known as the Green Revolution, an effect of which was that seed commerce was capitalised and co-opted by corporations into the oligopoly that it is today. Patents protect seed companies’ plants; genetically modified ‘terminator’ seeds sow sterile crops; and homogenisation pushes landraces—seeds tailored to their locale—into extinction. Cheated of their means of production; saddled with mounting debts; and fighting international trade prices: many growers have lost their raison d’être; in 2020, the most likely cause of death for a US farmer was suicide. The potency of a crop with such an ascribed value being handed out free in a global seed exchange might be the most resounding legacy of Wheatfield – A Confrontation: four decades hence, across the planet, the progeny of this once priceless quotidien crop continues to grow, a living testament to the fallibility of human value.

If one crop were to represent the idea of human ‘progress’ in Western Eurocentric narratives it would be wheat. The link between grain and state is one that James C. Scott explores in Against the Grain (2017). He highlights how grain cultivation was integral to the formation of the earliest states. His inquiry suggests that sendentism was forced on early people to create a grain core from which the state could grow. His notion of the genesis of agriculture pulls it away from the bucolic idea of settling, and instead suggests a long history of enforced settlement. The importance of grain to the state remains as prevalent today as in prehistory. Reshowing Denes’s work in the current climate is particularly affecting, overshadowed as it is by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Ukraine, known as ‘the breadbasket of Europe’, boasts some of the richest chernozem soils on the planet, perfect for grain agriculture. Prior to the war, the country was one of the largest global exporters of wheat, however, the ongoing conflict and the grain deficit it might incur has become a concern for global food security. Historically, grain shortages, and the inflation they cause, have been portents of civil unrest, even catalytic in sparking revolutions. Marie Antoinette’s apocryphal “let them eat cake!” was in response to bread shortages that helped ignite the French Revolution; and in 2011 Egyptians took to the streets chanting “bread, freedom and social justice”, during the Arab Spring. By planting the grain of our genesis at the feet of our cultural zenith, Denes’s Wheatfield was a powerful reminder of our fragility. Glimpsed from the ivory towers of hegemony, this unassuming field must have humbled even the most senior of executives.

Today, the plot on which Denes’s wheat grew would be valued at $13.4 bn, giving each grain the price-tag of $1,047.41, a potent reminder that Wheatfield – A Confrontation is as relevant as it ever was. With this fleeting work, Denes planted a seed of doubt in our hegemonic systems of power, a seed whose legacy still grows across the globe. Wheatfield, in the 40 years since its planting, has burgeoned into a global cry for change.

Barney Pau is a chef, artist and student on the MA Art & Ecology program at Goldsmiths University. Currently, his practice explores the connections between contemporary consumption and the codified norms of domesticity, playing with the symbolism of home by queering it. When he’s not baking bent bread, drawing gay toile wallpaper, or painting erotic landscapes, you can usually find him foraging for his food or reading books on bread.