Róisín Tapponi in Conversation With Shirin Neshat

Since CIRCA first broadcast on Piccadilly Lights with Ai Weiwei on 1 October 2020, a new conception of freedom and imagination has begun to take hold, one that reminds us of our collective potential to remake the world we inhabit. Together, emerging and established voices are recentering both art and social change, not as the fringe activities of elites or radicals, but as roles essential to human life. In an open letter published earlier this week, Shirin Neshat, Ali Abassi and Bahman Ghodabi invited people around the world to further echo the rallying cries of Iranians for freedom. Through this cross-atlantic response and countless others, hope prevails.

In response to this urgent commission, curator and critic Róisín Tapponi connected with artist and filmmaker Shirin Neshat over Zoom to discuss her CIRCA 2022 commission WOMAN LIFE FREEDOM.

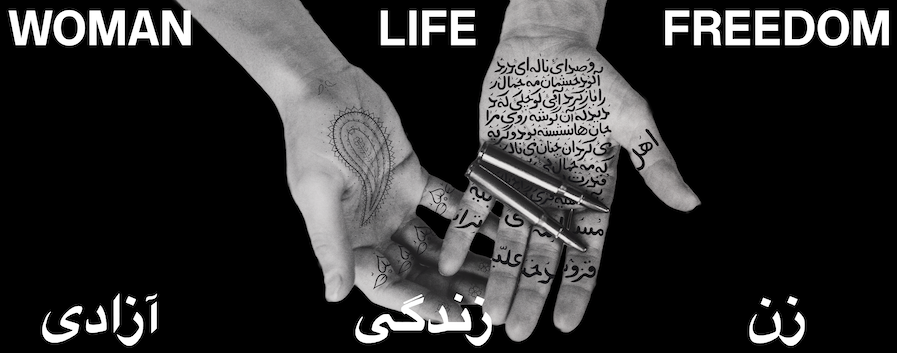

Róisín Tapponi: Thank you so much for joining me. Could you talk a bit about this work that you have produced for CIRCA, in commemoration of the death of 22 year old Kurdish woman Mahsa (Zhina) Amini?

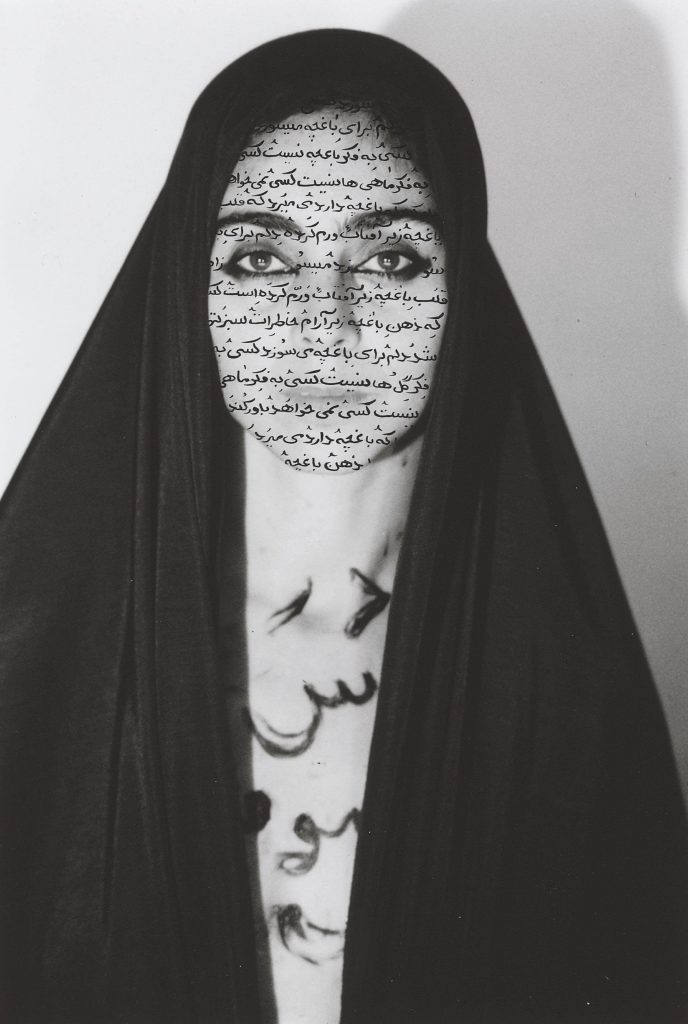

Shirin Neshat: I have been working with CIRCA to find the most eloquent and meaningful way to expresses my solidarity with people in Iran. For decades, my work has focused on on the plight of Iranian women, and how Iranian women’s bodies are used repeatedly as a battlefield for the men’s ideological, religious and political rhetoric. Iranian women have no control over their own bodies. Women are caught in a rhetoric of violence and fanaticism, compared with the ancient part of our history which is extremely mystical, poetic and anti-violent. I think contradiction is the core of Iranian identity: to be caught between a spiritual interpretation of Islam, and a fundamentalist practice of Islam. The image speaks about that kind of identity conflict and dilemma that women are experiencing. The government has imposed regulations, moral codes and political ideology on women’s bodies for too long. Women are saying: enough is enough. The bullets versus the paisley in the work, I mean, that says everything: the bullet being the symbol of this government, the paisley being the motif, that it’s a symbol of a more lyrical and more beautiful and and human and mystical tradition of Persian tradition.

RT: This image you made is lifted from a photography series you made in the late 90s, Women of Allah. How has the women’s movement in Iran shifted, or evolved, since then? Do you think progress has been made?

SN: Women of Allah captured a moment in Iranian history, the Islamic Revolution. At the time, some religious woman became militant and joined men in progressing the ideology of Islam. I explored this paradox: how is that possible that a woman who gives birth, is also capable of ending life? I wasn’t endorsing it. I wasn’t criticising it. I was just questioning it. It’s very important to say that this work was not about all women, but a minority of woman. I mean, today, you still see female moral police officers in the streets of Tehran harassing young woman. These are the people who are who are submissive to the fanaticism that the government has brainwashed in them. And so, of course, a lot of people misunderstood the work. But really, it was just a capturing a moment of Iranian history, when fanaticism was practiced by a minority. Soon after, the people of Iran really tried to move against that. And I would say that, as a result, the majority of Iranian people are not religious people. Many are forced to wear the hijab just because they have had no choice. Women of Allah, I think, no longer is relevant to the women of Iran today, who are revolting and saying, ‘keep your hands off of my body’ and ‘keep your religion at home’. That’s the reality of today.

RT: Women are fighting for the right to choose.

SN: Absolutely. We say to women who like to wear the hijab: do it. This is what democracy looks like. You can do that, but don’t tell me that what to do.

RT: Your life and practice is a continuous series of reinventions, and now aged 65, you are only becoming stronger, braver and more creative, experimenting with new mediums. What is your driving force?

SN: I’m so glad you asked this question. I always want to start over again. I want new beginnings. As I get older, I want to be a young artist, meaning that I want to take risks. I want to act like I’m just doing something for the first time. I think there’s something very exciting about not repeating yourself, not knowing. The danger when you have some success or some kind of signature work where people identify you with it, is to repeat yourself over and over again. I always want to be a student. I also want to remain in that state of constantly rediscovering myself as a person, as an artist, and challenging myself. This is part of the reason that I’ve experimented so much with new mediums, because each time I’m starting over again. I don’t know quite what I’m doing, and I don’t always make great work. I make a lot of mistakes, I get a lot of criticism, sometimes I make mediocre work. But the point is: we are not here to make masterpieces. We are here to experiment, to explore. It’s very ambitious of me to do that. And therefore I create a lot of fire for myself but you know, that’s part of being an Iranian woman! I’m very rebellious when it comes to being told how I am supposed to function as an artist, in the art world. I’m not scared of art critics, even if they destroy me. I don’t care about how I’m viewed, you know?

RT: On the fact of identity, as an Iraqi woman, I can’t put into words how much you’ve inspired those of us who are from the region, working in the arts, living in the diaspora. We’re here because you kicked open the doors for us!

SN: That means so much to me. Thank you.

RT: And you’ve lived in the US now for a few decades. How do you maintain and cultivate your deep relationship with Iran, and with Iranian women?

SN: You know, for the last two weeks, my life has stopped. I haven’t been able to focus on anything else. My career has taken a backseat. In a very natural way, I’ve gravitated toward what’s happening in Iran. It seems immoral to even think about my own self interests right now. I see the images of young people on the streets dying… Putting their lives at risk. And literally, literally day and night, I am focusing on doing everything I can to spread the word among people who don’t really follow the news, and have been quiet. I’ve also been very active in the Iranian community, and the Iranian media, because more and more I’ve been told that the voice of Iranian artists living in the diaspora means a lot to the people in Iran. We have an international and public voice that they don’t, and it puts some pressure on the Iranian government. So it’s been very draining, and I’m really fatigued, but I feel very much connected to the community. That is not something I do by choice or decision. It’s just inherent within me, including my husband, who is glued to the news right now, and all my friends, because I work with Iranian people. The diasporic community outside of Iran is doing every possible thing we can to support our people.

RT: Do you think art can function as direct political action?

SN: Absolutely. To give you an example, a young singer named Shervin Hajipour just released a beautiful song. You can follow him on Instagram! It is so moving, it is about what has been going on in the last two weeks. It’s a short history of Iranian people’s pain, living under this authoritarian government. In two days, they arrested Hajipour and put him in prison. This song has become an Iranian anthem, and now it has been covered and reshared so many times, because it moved us immensely. The song is filled with emotions and sentiments of rage and anger. And I don’t think any slogan, any politician, could convey the people’s emotions like him. The best anyone could have done is a two minute song. And so it is testament to the power of art, you know, in the way that it crosses all boundaries. It speaks to the people. About the people. There are many, many artists who have created artwork in response to the past two weeks. But this is an example of a man who immediately became a threat to the government, because they knew how he touched the masses. And people are really demanding his release.

RT: You mentioned that the song is being covered by other artists, and reshared. What role does social media play in this movement? And how, globally, can we use social media to show solidarity with the women’s movement in Iran?

SN: Iran doesn’t allow any real journalism in Iran except their own propaganda. It’s so critical to share what’s happening on social media, especially these days, when we’re at the verge of a revolution. That is testament to what is occurring today, there are massive protests happening everywhere in the world. It could be the turning point. And if this is not covered by the international media, television channels, newspapers and social media, and all of that, it doesn’t get the necessary attention. This is why I’m talking to everyone that I can to just say please spread the word, because that’s the only way to break this government.

RT: And what can the art world do to meaningfully support women’s liberation in Iran?

SN: I’ve been rather disappointed by the art world. There’s been celebrities who have spoken out from the music and film industries, from Angelina Jolie to Kim Kardashian, and God knows who else. But the art world, the museums, galleries, the artists who have a really important presence and a place in culture, have been very quiet. Yesterday, myself and Jerry Saltz posted on Instagram, pleading to the international art community, to the Whitney Museum, Tate Modern, the Guggenheim, Marina Abramovic, Cindy Sherman, all of the women and men who have a big career, who have a huge following: spread the words. We all have to participate and be politically conscious. Being an artist is not about just benefiting your career. I’ve been very disappointed that we haven’t seen such a reaction from the art world.

RT: Yes. And that’s what makes your work even more meaningful. It impacts a lot of people, those who are experiencing this in a very emotional way, and those who aren’t so aware of what’s happening. You’re really touching everyone with your words and your wisdom.

SN: We have a responsibility, I think.

RT: What does freedom look like to you?

SN: Freedom is a life where no-one tells you who to be, how to be, or how to function. Freedom is when you make every decision for yourself, not your government, not your religion. Freedom is for people who understand the value of it. I think, unfortunately, some people have been born and raised in countries that they’ve never even tasted freedom. They don’t even understand what it’s like, where you don’t have to live every day conditioned to someone else’s concept of morality and ideology. The people who are protesting in Iran are 16 years old, 22 to 25. They’re saying: why is the West allowed to be free? I’m not. I didn’t choose this life. I didn’t choose to be religious. I didn’t choose to be living in this way. I want to taste that. Freedom is basic human rights. And no one—no government, no system, religious or not religious—has the right to take that away. ∎

_

Róisín Tapponi is a film and video curator, critic and PhD candidate based in London. She is the Founder of Habibi Collective, Founder CEO of SHASHA Movies, Founder EIC of ART WORK Magazine and Founder of Independent Iraqi Film Festival (IIFF).

Tapponi works at the forefront of film and video from South-West Asia and North Africa (SWANA). She has curated exhibitions and film programmes at numerous international institutions such as The Academy, MoMA, Anthology Film Archives, Chisenhale Gallery, Africa Institute, Gasworks, Art Jameel, Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), and delivered masterclasses and talks at BAFTA, Locarno Film Festival, CPH:DOX, Sheffield Doc Fest and more.

She is a regular contributor at Frieze Magazine, over the past decade she has written for publications including The Guardian, Artforum, Vogue US and GQ. Selected press features about her own work appear in publications such as TIME Magazine, Vogue Magazine, Office Magazine, Sight & Sound, Dazed, GQ. She was on the cover of King Kong Magazine.

She is the recipient of the ‘World Leading PhD Art History Scholarship’ at University of St. Andrews. She has guest lectured on film at universities including Oxford University, UC Berkeley, the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London (UCL) and Northwestern University.

She is Iraqi & Irish based between London/NYC.