Sojung Jun: From Agent Orange To Intoxicating Green

Written by Dr Cleo Roberts-Komireddi

A verdant stretch of land separates the Korean Peninsula into North and South. It is four times the size of the Seoul, South Korea’s capital, and with immense wetlands and significant mountains it is one of the world’s largest conservation areas on a par with the Amazon rainforest. It has the simultaneous accolade of being the world’s most fortified border. The expansive strip is bound in barbed wire, lined with thousands of troops and laden with unexploded landmines. This is the buffer, known as the Demilitarized Zone and the Civilian Control Zone, between North and South Korea. Instituted following a ceasefire in 1953, it has lain unpeopled for over six decades.

What has been carved into the landscape to separate these nation states also connects them. While the zone provides human security, it also provides ecology security. For this land, empty of people, has become a safe habitat for near to 2000 species of wildlife, including endangered and protected species. It contributes to regulating flooding and erosion. In sum, it is an unintentionally rich ‘living laboratory’.1 Sojung Jun’s new film, ‘Green Screen’, 2021, takes us here to her ecotopia. The radiant mirage interrupts London’s, Tokyo’s and Seoul’s architectural density. And an ostensibly lush paradise exposes itself to the many buzzing about these urban centres.2

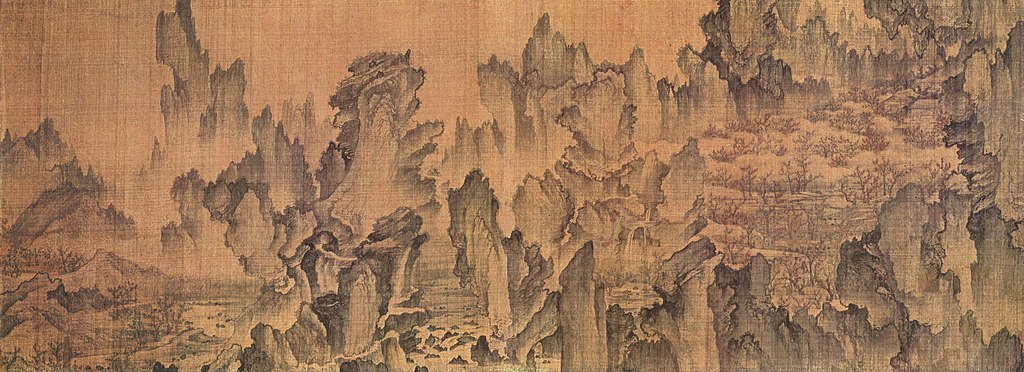

The blazing green habitat is, in ways, connected to London and Japan as it is to Korea. If we think of ‘weather-worlds’, a phrase coined by anthropologist Tim Ingold, we are immersed in a shared atmosphere. Life is lived in atmospheric conditions. ‘Within the animic cosmos’, Ingold explains, ‘the sky is not a surface, real or imaginary, but a medium’.3 And it is integrated with earth through the lives of its inhabitants. This is not the most groundbreaking of propositions. To regard nature and humans as dichotomous was, traditionally, a misnomer in East Asia. ‘Humans were’, as Kim You-Joong notes, ‘understood to be part of nature within the general order and harmony of the cosmos’.4 To read a sijo, a three-line poetry genre of the Joseon period, is to learn about human life embedded in nature. To look at a handscroll made by An Gyeon, a notable artist of the early Joseon period, is to appreciate the admiration for nature. Mongyudowondo (Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Land), 1447, is a journey through jagged mountains. Read from left to right, they rise, fall and open out into soft pools of water and banks of trees. Rendered in three-point perspective this geography slips from reality into dream recounting its commissioner’s, Prince Grandgun Anpyeong, utopic vision of a stroll into a peach orchard.

Jun’s work syncronises with this regal fantasy. ‘The painting proposes to me an allegory of history and the present…and an attitude that allows me to look at a single landscape or time in multi dimensions’.5 From an elevated viewpoint, ‘Green Screen’ moves through a landscape. The staggeringly verdurous panorama fizzles and crackles with digital dots. It’s pocked red and infected with acid green patches. This deterioration is Jun’s slide between a real and dreamlike state. And in these stutters and glitches lie a self-consciousness of the electricity and data networks, what Lewis Mumford described as the ‘invisible city’,6 it takes to enable the film’s circulation.

These digital jolts might also be a subtle clue and allusion to the contextual depth of the Jun’s film. An Gyeon’s referential handscroll itself is subject of a feud between Korea and its ‘owner’ Japan. Speaking to the countries historic animosities, Mongyudowondo is a Japanese treasure said to be loot during the Imjin War (1592-98). It resides in the collection of Tenri University Library and although a pervasive part of the Korea’s visual repertoire, the original has rarely been seen. Its mystique is such that the painting is personified and in 2009, on a rare occasion it was loaned, Mongyudowondo was said to have ‘visited’ Korea. Crowds came to see the masterpiece that has become emblematic of Korea’s sophisticated heritage.

Equally embedded in Jun’s arcadia is the history of man-made tragedy that made this hermetic environment obligatory. The consequences of human conflict have been the conditions for an extravagantly bio-diverse culture that has stimulated a campaign for its conservation as a ‘peace park’. Jun reads this ‘twilight zone’ for not just its ecological hospitality but ‘ the countless moments of hostility and hospitality attempted between the two Koreas’.7 Early Arrival of Future, 2015, might seem to make big the promise of hospitality. On a concert hall stage, under the glare of spotlights and in the crosshairs of multiple cameras, an intense piano duet is performed. The pianos almost kiss each other. One of the players is a North Korean defector. The other is from South Korea. The music is their joint composition, the result of a protracted collaborative process engineered by Jun. In the melodies merge folk and children’s songs from each side of the border. And while the players are united in sound and space there are hesitations. Pointed looks are thrown across the soundboards. And this parabolic vision, like her gestures in ‘Green Screen’, skews and blips.

In both the film’s quiet disturbances, through the visual glitches and musical jars, Jun replicates Korea’s trajectories of clash and consensus. Accentuated by being blown up for street scale, she conjures visual sequences that project the potential for peace with the acknowledgement of the patience and pain it will take to get there.

1 Kim, Kwi-Gon. The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) of Korea: Protection, Conservation and Restoration of a Unique Ecosystem. (Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013) p.xvi

2 People passing Piccadilly Lights belong to the consumer classification groups: ‘City Sophisticates’, ‘Lavish Lifestyles’ and ‘Career Climbers’ according to Ocean who manage the site

3 Ingold, Tim. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. (United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2011) p74

4 Kim, You-Joong. Restoring Eastern Thought: The Eco-poetry of Kim Ji-ha and Choi Seung-Ho in Korean Literature Now, Volume 29, Autumn 2015

5 Email interview with the artist 24/07/2021

6 Mumford, Lewis. The City in History. (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1961)

7 Email interview with the artist 23/7/21

Dr Cleo Roberts-Komireddi writes and speaks on contemporary South and Southeast Asian art. She has written for leading publications across the world, including The Guardian, the Spectator, Times Literary Supplement, Frieze, ArtReviewAsia and ArtAsiaPacific. She’s contributed to books published by Phaidon and Thames & Hudson and has lectured at Sotheby’s Institute, Princeton University, University of Cambridge, Royal Asiatic Society.