Cassandra Press: A Monument A Ruin

Written by Stella Bottai

In 2021, artist Kandis Williams – founder and editor-at-large of Cassandra Press, an artist-run publishing and educational platform producing lo-fi printed matter, classrooms, projects, artist books, and exhibitions – was invited to participate in Pompeii Commitment. Archaeological Matters, the first contemporary art programme commissioned by the Archaeological Park of Pompeii in Italy. Williams proposed to begin new research on the theme of Pompeian programmata – the political propaganda graffiti –, particularly to investigate possible parallels with the politics of representation and strategies of social resistance at stake within contemporary democracies, in particular in the United States.

As part of her research, Williams met with Pompeii’s former Director and archaeologist Prof. Antonio Varone, responsible for the indexation and study of all of the Pompeian painted inscriptions, to address questions around Pompeii’s localised history as a provincial town and Roman colony, and how its electoral propaganda through the use of graffiti may possibly speak to more universal questions relating to the political agency, voice and representation of socially oppressed categories in today’s Western societies.

In the wake of Black Lives Matter’s global uprisings in 2020, the use and symbology of graffiti in public spaces has taken on new and powerful significance and influence, prompting an urgent reflection on the meaning and manifestation of “collective history” in the public domain, particularly in the context of memorials and statues tied to slavery and colonialism. Is it possible for such monuments to be turned into ruins, and for those ruins to be monuments? Arguably, yes. In June 2020, American Confederate general Robert E Lee equestrian statue in Richmond, Virginia, was covered in anti-racist graffiti; a portrait of George Floyd was projected onto its main side at a monumental scale. This layered image was an omen of the eventual removal of Lee’s statue from its pedestal, in September 2021, which remains in place covered in graffiti from the 2020 uprisings. Among those who did not welcome this event was former US President Donald Trump who released a statement decrying the “complete desecration” of the statue. “Our culture is being destroyed,” he wrote. Whose and which culture, are the questions.

An exceptional amount of painted wall inscriptions – known as tituli picti – survived Vesuvius’ eruption in 79AD, making Pompeii a unique site for the study and comprehension of the social environment as a canvas for individual expression since ancient times. From the beginning of Pompeii’s excavations in the XVIII century to the present time, a great amount of tituli picti have been recovered, mostly in Latin, often found in locations of public transit and attendance, authored by citizens of different status and class. Contrary to today’s customs in much of the Western world, where graffiti are often regarded as unauthorised expressions linked to crime or degradation, wall inscriptions in Ancient Rome were not surrounded by negative connotations and were commonly accepted as an accessible tool for advertisement, to publicly share opinions and announcements. One of the most influential type of painted inscriptions were the programmata, electoral propaganda endorsing the candidacies of politicians in municipal elections. These brief epigraphs, which used abbreviated formulas, were generally written in red or black paint along the public-facing walls of well-travelled streets, and were signed by the person, of the trade or craft association, or of the sporting or religious society, that supported the candidacy. Featuring a great number of names for both candidates and supporters, the programmata thus offer a layered resource to learn more about public life in Pompeii and its participants, including the political agency of groups, such as women and slaves, who were not entitled to the right to vote.

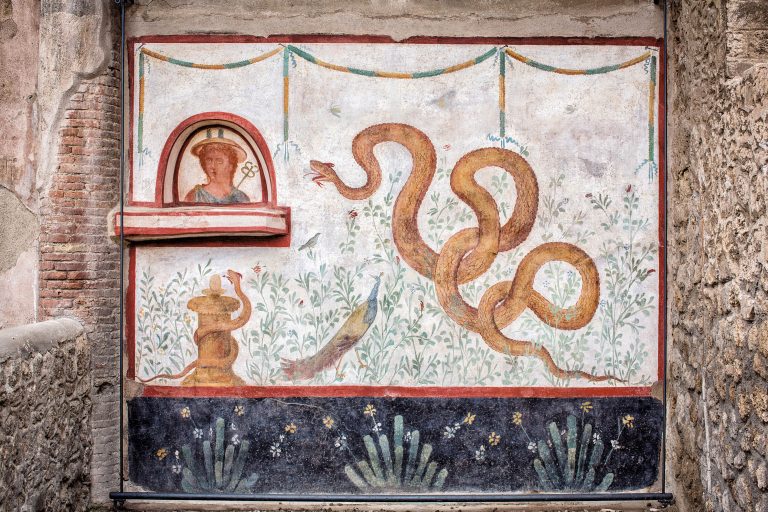

As a culmination of this research, Cassandra Press shared a new reader on pompeiicommitment.org research portal, titled “Graffiti Monuments Movements and Democracy”, comprising scholarly literature on Pompeian inscriptions, and documentation on confederate monuments across the United States. Interested in Pompeian heritage as a catalyst for pursuing a dissonant space in which monumentality and ruination may coexist, Williams also invited photographer Brandon English to collaborate on a new series of photographs shot in situ at Pompeii over two nights in Summer 2021. English’s visual accounts from the Abolitionist Group Protests and Assemblies in New York, throughout 2020, were projected onto different buildings and frescoes in Pompeii, including the Temple of Isis – a sacred building dedicated to the ancient cult of the Egyptian goddess – and House of Cryptoporticus. Introducing English’s photographs into the nocturnal landscape of the archaeological site thus produced a new visual symbology, one that empowers Pompeii with the trans-temporal, phenomenological possibility to be a testimony and a rupture at once.

Williams’ research in Pompeii has more recently developed into a new moving image piece titled A Monument A Ruin, commissioned by the digital art platform CIRCA in collaboration with Pompeii Commitment. Archaeological Matters. Presented within the framework of Cassandra Press’ publishing and educational work, the work is broadcast everyday across the CIRCA network of screens in London, Los Angeles, Melbourne, Seoul and Tokyo throughout February 2022. Drawing on the “Graffiti Monuments Movements and Democracy” reader, A Monument A Ruin takes the form of a short audio-visual lecture collaging together graphic treatments of ancient programmata and statues, with contemporary protest graffiti and monuments – some featured through their presence, some through their perceivable absence. These are juxtaposed with Williams’ and English’s photographs shot in Pompeii, whilst an accompanying soundtrack includes a summary of this essay, narrated by artist Elliot Reed, and Brandon English’ reflections on the nature of his photographic practice and the importance of using a vertical frame in the work.

Within the short duration of two minutes and thirty seconds – the length required by the screening format – A Monument A Ruin traces the foundational moments of Williams’ investigation and interest in highlighting possible parallels across distant epochs, looking at the act of writing on walls as a practice of mark-making with political agency. Those who follow Williams’ Instagram account will be familiar with the artist’s interest in watching and amplifying user-generated short videos on platforms such as TikTok or Instagram which, through accessible and relatable language and visuals, provide educational opportunities to learn about lesser-known historical narratives and critique, often in connection with Black history. Whilst the complexity of Williams’ video-lecture is far from being a social-media-friendly composition, it does establish an accessible and focused space that can hold and nurture knowledge amidst the busy environment of advertising billboards – telecasting platforms whose politics and purpose are arguably not too dissimilar from those defining social media.

Recent critique has proposed to draw parallels between parietal inscriptions found in Pompeii and contemporary social media, arguing that ancient wall inscriptions established modes of individual expression and public engagement with information alike today’s online media environments. It is interesting to think about the question of how public space is regulated as a shared environment, imagining space not only in terms of physical areas but also as a world unfolding digitally online. Is visibility granted to everybody equally? Which and whose words are prioritised, what language is lost? A historical example from Pompeii’s heated electoral campaigns sees candidate Caius Iulius Polybius rapidly having the names of two sex workers – Cuculla and Zmyrina – covered up with a layer of white lime as they had dared to take a public stand expressing their support to his candidacy through a signed painted inscription in his favour. As Prof. Varone describes in a recent text: “these women, with their way of life, lavishing praise on him, the propagator of ancient customs, the preserver of ancestral traditions! It would have been counter-productive to accept their support; it might have undermined the moral character he had been patiently constructing over the years”.

Thinking about the manipulation and control of public perception in today’s context, it is a known fact that social-media algorithms such as those deployed by Meta (formerly Facebook) will extensively undermine the circulation – and therefore the visibility and accessibility – of content dissenting from the political alignments and interests of powerful Big Tech companies. The paradox of how one may introduce and place attention on the disruptive expressions of truth and radicality of political protest within scrutinised public environments – online or in an urban context – yet without compromising the very disruptiveness of their truth and radicality is one of the key challenges that A Monument A Ruinalso had to navigate throughout its making to legitimately screen in the public realm.

The composition of historical layers in the video establishes a form of image-making that brings focus to the present whilst encompassing a remote past, and feeds from and into loops of its own making. Pompeii provides both a source and a surface to remark the possibility of transformation which is inherent to the very fact of existing. Monuments turn to ruins, and ruins turn to monuments: is it about if, or rather, how and when they do?