Fiona Banner: MESSAGES IN THE SKY

Written by Alice Bucknell

In his 1964 text Language and Reality, philosopher Vilém Flusser scaffolds a planet of language. At its equator of reality are words at their most banal: conversation and small talk, everyday gestures at meaning. At both poles sits silence—both the authentic and inauthentic variety—a total refusal. Things get weirder in the hazy atmosphere above its two hemispheres, where a climbing latitude yields the nonsensical and prophetic: mumbling, poetry, word salad, prayer. While he never calls it outright (to name the thing is, in a sense, to lose it), Flusser drops hints that these sideways stabs at meaning-making are the most substantial and revelatory. These are the coordinates where language is sticky, vague, chimerical and airborne, buoyed by possibility, always on the cusp of becoming something else.

The British artist Fiona Banner, who also operates under the para-organizational seal of The Vanity Press, takes an adjacent approach to language. Across print and film, doctored photography and gargantuan ominous sculptural installations that thrust military jets and pneumatic navy appendages into the hallowed halls of soft power enclaves like Tate Britain, Banner toys with language as a plastic medium, both a brute weapon and seductive technology, whatever you want it to be. Like a car crusher at the cosmic junkyard of human civilization, language, Banner suggests, is the ultimate leveling device, compressing all worlds into a single consensus reality.

In DISARM, commissioned as part of CIRCA’s 20:24 programme, the artist’s latest project takes aim at the engineered phenomena of the military flypast—which Banner characterizes as both “uberexiciting” and “uberboring”—to explore the triple-pronged relationship among language, cultural performativity, and state-sponsored warfare. Referring to that militaristic aerial orgy as “a moment of ridiculously extreme weather”, Banner’s new video work concentrates on language and its deft weaponization suite. But in the shuddering sonic affect of a five-minute-long event that sends that splitting whine of overhead aircrafts rippling through the body, DISARM puts paralanguage—a kind of embodied communication that happens simultaneously beneath words, a semantic drift between what’s said and what’s really meant—at the heart of the work.

“There’s a strange bodily effect the flypast has on you, subliminally acting out some deep trauma about conflict, or perhaps a desire for it…” Banner reflects in London over a Zoom call as LAPD choppers hover ambiguously over me in Los Angeles. Even in the death rattle of empire, western countries are dexterous at peddling the fantasy narrative of violence at a distance. The flypast invokes a little taste of crisis LARP as a treat, its pompous planning pumped with millions of taxpayer pounds reinforcing the rejoinder that real violence could never happen here but always elsewhere. And yet as the chopper’s groan rattles around my brain I truly feel the weight of Banner’s theory, like an impromptu lecture performance, sensory stimulation tinged with a vague sense of dread. “Maybe a fighter jet is the limit of language,” she ponders, while I catch every other word through the noise.

The migraine-inducing cacophony of LAPD’s helicopter fleet is par for the course of living in Los Angeles—symptomatic of a police state’s chronically overinflated budget, dollars brainlessly burning carbon into an ever-heating planet that we all call home—but it’s been kicked into high gear this summer. Let it be known: summer ‘24 is the season for civil unrest, for Palestine, for the student intifada, for the absurdist Presidential combat of one war criminal up against another. But this is hardly a phenomenon isolated to the North American continent. Banner’s got her finger on the pulse of a broader sense of global disorder, and DISARM digs into the living wound of this feeling.

DISARM: a message spelt out plainly in the sky by a simulated fleet of global fighter jets (each letter is marked out in a different aircraft, forming an image of planes from varying nations). Banner’s vaguely prophetic rejoinder has roots, of course, in a much older technology. Behold, the fine art of skywriting—or blasting vaporized paraffin oil from a plane’s exhaust to etch a temporary message in the Earth’s atmosphere. A surprise to absolutely no one, this esoteric razzle-dazzle manifested courtesy of the British military and tabloids, premiering in the UK in the aftermath of WWI.

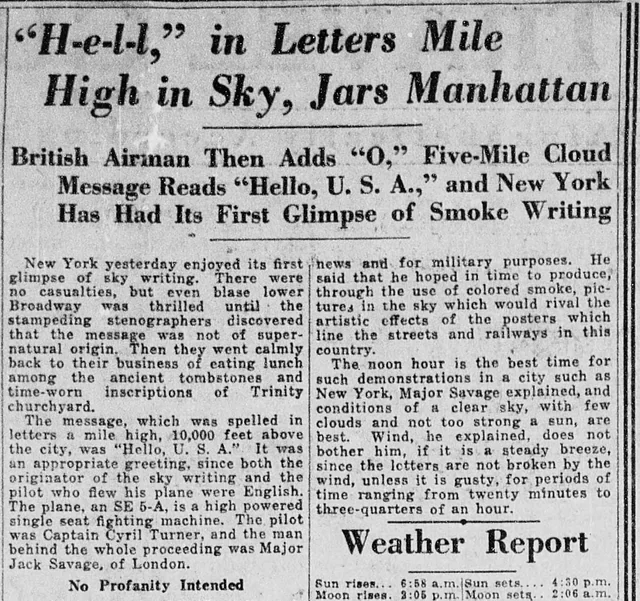

Skywriting’s mythic origin story goes like this: a Royal Air Force major named John C. Savage teamed up with a Captain called Cyril Turner to spell out the phrase ‘Daily Mail’ some 10,000 feet above the huffing horses of the 1922 Epsom Derby, effectively conjuring the world’s first atmospheric advertisement. As the duo expanded their emissive enterprise across the pond, contracts with Lucky Strike, Pepsi, and Ford soon followed. By the 1930s, the sky—which for thousands of years of human history had been a cosmic interface for speculating on worlds far beyond—had become a self-reflective funhouse mirror, a proto-television, the first environmental media for consumer capitalism to crassly hawk its wares.

Sky messages are ghosts. These artful vapor trails, whether the dense calligraphic flourish of a single pilot’s hand (skywriting), or the computational performance of paraffin dots spluttered out by formation flying (skytyping), are an imprint of a perpetrator long gone, a hard body that’s literally flown the scene. In DISARM, the CGI jets themselves, an imagined global fleet of various fighter jet models, spells out the language. Here, Banner merges message and messenger, forcing the military apparatus to speak for itself rather than hiding behind the haze of its exhaust fumes.

“There’s a paradox to the work,” Banner suggests, “the jets deploy a message that would effectively render them obsolete”. This ambivalence expresses itself in other facets of the video: the banal everydayism of the iPhone shaky cam; the apparent boredom or distraction of its holder, as the camera occasionally careens into psychedelic, rolling clouds buffeted by sunshine in the midst of the flypast ceremony. The quietly ominous beauty of the video’s context—bucolic surrounds, birds chirping—is seemingly indifferent to the militaristic song-and-dance happening overhead. It’s as if the work inhabits multiple worlds simultaneously. The lack of voiceover or spoken narrative keeps the whole scenario unbounded, allowing this sense of unreality to percolate.

“Conflict is a breakdown in communication,” Banner explains. “I’m interested in the gradual ways language erodes from being a metaphysical tool to being something so bluntly physical, when it fails and calcifies it becomes a caricature, or opposite of itself.” There is an idiocy to this deadened language that borders on the comical, perhaps no better articulated than the speculative fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin in her text, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (1991). Critiquing the “time killing arrow” of the techno-heroic, LeGuin takes aim at the hero’s journey—man throws spear, kills mammoth, enshrines the death in myth-making, and it’s this story of a singular violence that gets remembered, passed down through the collective campfire of human history. “The language of DISARM is so literal that it’s almost dumb,” Banner muses, “but close to dumb is where we find ourselves.”

Banner backs this idea in previous works, including her Full Stop series initiated in 1977: first, a tiny neon sculpture, followed by a multi-typeface family of finely carved and sanded white polystyrene periods. As time went on, the full stops became less polished, more urgent: in 2020, the artist, uninvited, delivered a 1.25 ton sculpture—black, ragged granite—onto the doorstep of Defra, the ministry responsible for protecting global oceans. By contrast, DISARM leans into the weightlessness of film; Banner leverages its lightness to comment on a global sense of unreality, that feeling of living in fundamentally different worlds.

As with any new technology, time is the ultimate corrosive: skywriting was largely replaced with TV advertising hardly a decade after its bizarre arrival. And yet, the collective trauma of COVID saw a resurgence of this strange art. While the majority of us remained locked indoors, planes scrawled health and safety instructions in the skies above Sydney. As Trump’s border politics grew more violent and bombastic in equal measure, independent pilots etched protest messages above the mountainous skyline of Los Angeles. Hearts, smiley faces, and other tender sigils appeared above countless other cities during lockdown like contemporary crop circles. As they slowly disintegrated over empty office towers and deserted highways, catching a view of one from the window of one’s personal quarantine zone was a moving experience: an airborne surge of feeling that couldn’t be embodied collectively down on Earth.

Tech devolves in a spiral, grafting onto different meanings and use values as it plummets back down to Earth. Frequently in our conversation, we orbit the inane showmanship of the military flypast—its hyped up and hypermasculine fervor that’s really about nothing, “an ultimately pointless image and ecological travesty,” suggests Banner, “a quintessential Britishism: the absurdity of the grandiosity, an image of having already having lost.” And yet in the inanity of its subject matter there is an urgency to DISARM that appears, trojan horse-style, through these elements of the satirical. I do some more digging on skywriting and discover a similar flightpath.

In downtown Manhattan in 1922, skywriting bros Savage and Turner accidentally stirred a micro-apocalypse through an unannounced product demo. Terrified onlookers froze mid-munch through their lunch break sandwiches as the letters “H-E-L-L” gradually manifested in the deep blue sky above, quite literally out of thin air, seemingly announcing the soft launch of an alien invasion. The pilot had at first forgotten the O. Then that sacred vowel appeared and time began again. I think of DISARM similarly as a magic spell and an impossible ask; a live response to the mixed-reality calamities of 2024; an atmospheric phenomena that unsticks a part of language from language itself; its meaning sneaking out through a trapdoor just before it fully congeals. Airborne like Flusser’s hemispheres, DISARM is always on its way to becoming something else.

Alice Bucknell is a Los Angeles-based artist, writer, and educator with a particular interest in game engines and speculative fiction. Their recent work has focused on creating cinematic universes within game worlds, exploring the affective dimensions of video games as interfaces for understanding complex systems, relations and forms of knowledge. They are the organizer of New Mystics, a digital platform merging magic and technology.

Their work has appeared internationally at Ars Electronica with transmediale, Arcade Seoul, the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, Honor Fraser Gallery in Los Angeles, Gray Area in San Francisco, Basement Roma in Rome, Singapore Art Museum, The Museum of Modern Art in Fort Worth, Texas, Fiber Festival in the Netherlands, and Serpentine in London, among others. Their writing appears in publications including ArtReview, e-flux architecture, frieze, the Harvard Design Magazine, and others.

In 2024, they are a part of the Synthetic Minds prototyping lab at Medialab-Matadero in Madrid (Jan—Feb), the More-Than-Planet Residency & Algorithmic Ideation Assembly (ARIA) Summer School in Ljubljana (Aug), the Enter the Hyperscientific residency program at EPFL in Lausanne (Sept—Oct), and the Collide residency at CERN/Copenhagen Contemporary (Nov—Dec).

Bucknell received a MA in Contemporary Art Practice from the Royal College of Art and a BA in Anthropology from the University of Chicago. They are a prior resident of Somerset House Studios in London and currently faculty at SCI-Arc in Los Angeles.