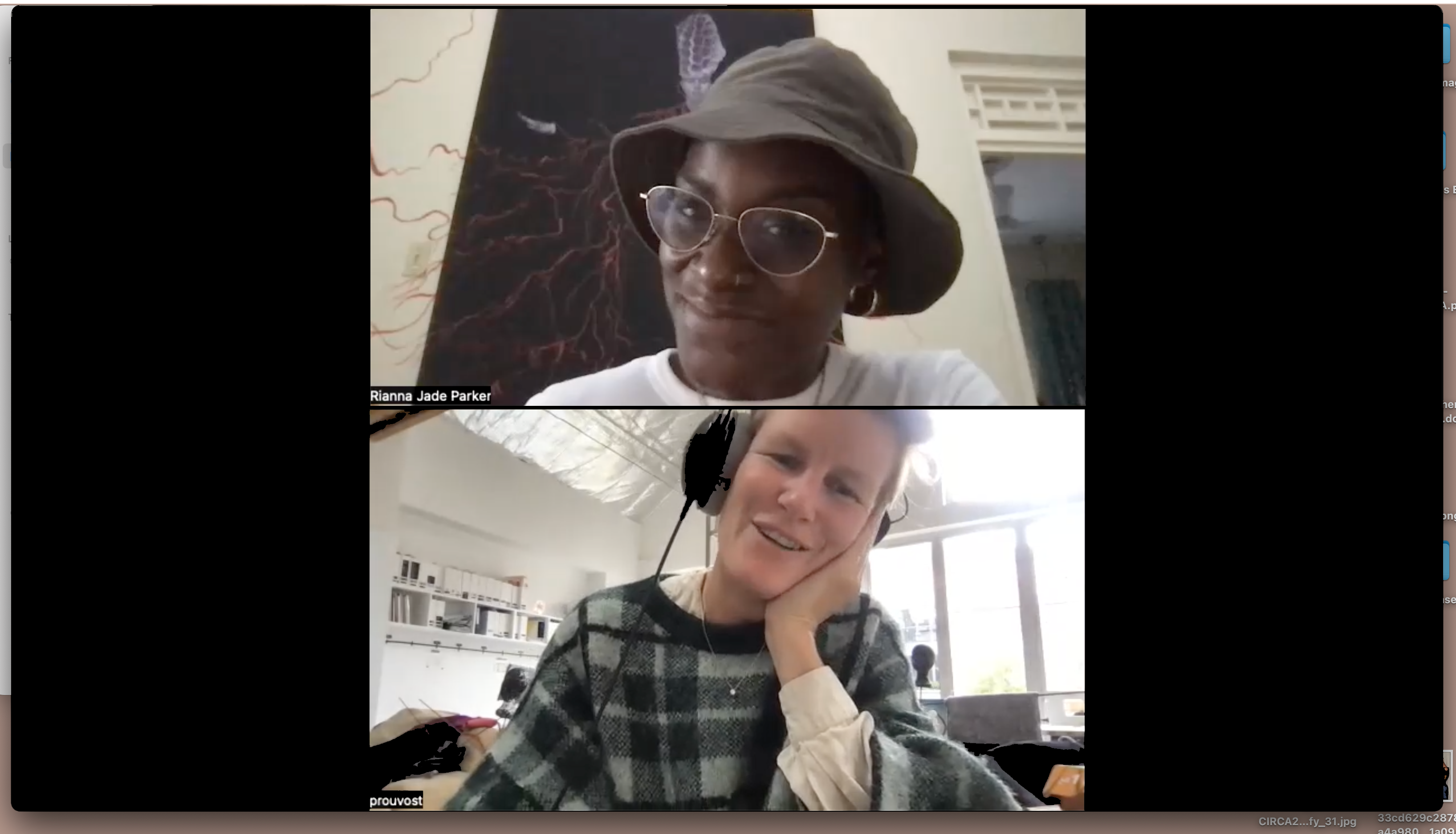

Rianna Jade Parker in Conversation With Laure Prouvost

Turner Prize winning conceptual artist Laure Prouvost talks to critic and curator Rianna Jade Parker on the eve of her October commission ‘No More Front Tears’ launching for CIRCA 2022. Connecting over Zoom – with Laure in her studio in Antwerp, Brussels and Rianna in Kingston, Jamaica – they discuss the medium of public art, migration memories and Laure’s enduring fascination with the octopus.

Rianna Jade Parker: With your new video work No More Front Tears for CIRCA, do you feel like you’re responding to a personal or global situation?

Laure Prouvost: It’s a bit of both, I mean, the screen, the scale and the size and the directness of it. I wanted something that could be as direct as it’s meant to be. I didn’t want to subvert what it’s made for. But to use it as a billboard, as propaganda, as adverts in the way advertising does. And this video, the whole thing talks a lot about migrations, movement, human, nonhuman, other than humans. You know, all this could be seen personally or much more global of course. It’s about birds and also the way we use the planet and the struggle of animal life to move. But also human life. I’ve moved, mostly in Europe, so I’m not a big migrator but I feel like, still each time you have to root yourself again. Root yourself or find your history, your connection to a place. And so I think it’s always an on-off feeling of feeling connected and then disconnected. I think it’s all about these emotions. But I experience it much softer, I think people with dramatic migrations are very different. But still, I think from one perspective, you can feel empathy. You can still feel empathy and desire, empathy and desire. And I think, so having Brexit, the whole story of Britain sending migrants to run. All this sort of extreme politics, I must wake you up as well as an artist. Try to, if you have a chance, have your voice heard a bit, take the opportunity.

RJP: What’s your strongest migration memory?

LP: I have moved just from France to England. That was the first migration at the age of 18. Having a very poor understanding of the language, you know, misunderstanding things, miscommunication, mis-getting things and trying to tackle this. Understand this new place, but also the freedom of not belonging sometimes, you know. The freedom of not having to fit in. But it’s also just a gathering of voices and people you meet.

Recently we lived for three or four months with Ukrainians, who just arrived, in our home. To visit another kind of migration which was close to us, but the subject is quite different, I don’t want to position myself. It is very much a migration of the seeds, a migration of materials or products. As a kind of single service in this world that we reach now, you know, the complexity of customs. And now the isolation of England through their customs, and so I think it’s idealistic and it’s completely unrealistic as we talk about in the piece. It’s lucky in art, you can make no sense. So you can propose things which are right now completely stuck.

RJP: I’m interested to know what themes, places or people are integral to your work. What were some of the immediate references that helped you make up this concept to make this new video work itself?

LP: When I did the Venice Project for the French Pavilion it was very much more about trying to make a film which was an octopus, an octopus that could pass through tiny cracks. And then also each character, each person, we were ten people that I met along the way of the making. Which, one was a dancer, one a magician, from all different kinds of life paths, you know. And we met and we could each be one tentacle of this body and spread and touch each other and have a cool body. But with the octopus, the brain is in the tentacle. So it’s not controlled by the one mind, but more by a lot of collaboration, a lot of feeling and touching. So for this reason I work a lot with musicians as well. We would try to translate different emotions together, from one medium to the other. Then there is the project I’m doing with Lisson gallery as well. In the Frieze London booth and that’s trends, human trends, animal trends like free female bodies and octopus and hands coming out. So it’s like kind of the world’s mixing into one. And that’s still around, I mean they all for me would connect on this four week. project.

RJP: Is there something special about the octopus or just the idea of having multiple limbs? Are tentacles particularly interesting or are you thinking around limbs in general?

LP: It’s for me this end of the beginning of my brain and life from the planet, especially as the brain is not centralised. I think it’s a kind of symbol of, I hate symbols, but it’s a kind of way of being just able to push our own brain to adapt into maybe more complex beings or sensations through different ways of physical adaptations.

RJP: In the film there is a text prompt and occasionally a speech saying ‘no more front tears’. What did you intend to mean by this?

LP: I kind of came and fell on it and the word was front tear. And it was to say no more sadness of separation and families and kids and no more fronts that create extreme traumas. With Brexit, I mean, of course I’m talking to the UK at the moment, but it was very much how it created so much. I mean, it’s centuries obviously …So yeah, it says what it says really. No more drama.

RJP: In your film a voice is also encouraging people to pick up a placard and join a march. I wonder, what was your last march?

LP: My last march was Brexit. But I think there was another, there was of course in Brussels there’s a lot of cycling marches and also women’s rights. But yeah, I think the idea is not especially that people have to take placards to that cause. There’s just the idea that you can, we can just hold a placard in our mind or our head in the way we talk, the way we go through the world, the way we cross the ‘frontier’ by just talking to someone. You know, like crossing our privacy, or crossing our own comfort zone. It is basically crossing the comfort zone.

RJP: I wanted to ask, if you feel that public art is always useful and necessary? You know, it’s now far more popular and expected. Most Londoners interact with Picadilly Circus at some point in the week or the month, it’s a nice junction. I personally, very rarely notice anything being screened that is not a McDonalds, Coca-Cola and car advertisements, and that’s down to effective branding. But with your film, I can see exactly the ways that my eyes and other senses will be grabbed and skewed when walking through a pedestrian area. What were you thinking, when you thought about that public space and the artwork?

LP: Well, every time you get an invitation, it’s about the work responding to a place, you must be very aware of its surroundings, that’s the way I work, to a situation. I’m not an artist who works in isolation, it’s more about the situation and it could be very personal, or it could be global.

RJP: What do you think makes a successful piece of public art? I mean for you, forget a wider sense.

LP: It’s already a political sign to give these three minutes to artists. It already has its own value. It provokes certain emotions and I feel like when it’s yours that’s maybe when it works. But it doesn’t belong to the artist anymore and it’s kind of interesting that it can take its own course and evolve. So maybe that’s when it works for me, it’s lost its identity of the one maker, possibly.

RJP: If you were a bird or had wings, what migration route would you choose?

LP: Ever dream of flying when you dream?

RJP: Sometimes. I dream of floating a lot. If I had wings, I think I would like to fly around the Caribbean Sea. I’d like to go around the entire perimeter of the Caribbean Sea. Inter-regional travel is very difficult and expensive. There are not any direct routes between a lot of islands and so often, the only option is to redirect through the U.S. This requires a VISA, which is no easy feat for most Caribbean nationals.

LP: I would love to be a bird, I mean, to be able to fly. So I mean, just let myself be. But I would like my loved ones to be able to follow me in the wings. I actually would fly to London now. To fly to say hello to my friends. Land on top of the smoke screen.

_

Rianna Jade Parker is a critic, curator and researcher based in South London where she studied her MA in Contemporary Art Theory at Goldsmiths College, University of London.She is a founding member of interdisciplinary collective Thick/er Black Lines, whose work was exhibited in the landmark exhibition Get Up, Stand Up Now: Generations of Black Creative Pioneers at Somerset House, London. She is a Contributing Editor of Frieze magazine and co-curated War Inna Babylon: The Community’s Struggle for Truths and Rights at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

Her first book ‘A Brief History of Black British Art’ was published by Tate in 2021 and she is represented by The Wiley Agency.