Cemile Sahin, winner of CIRCA PRIZE 2023, redefines political narratives through pop culture in ROAD RUNNER

Interviewed by Vittoria de Franchis

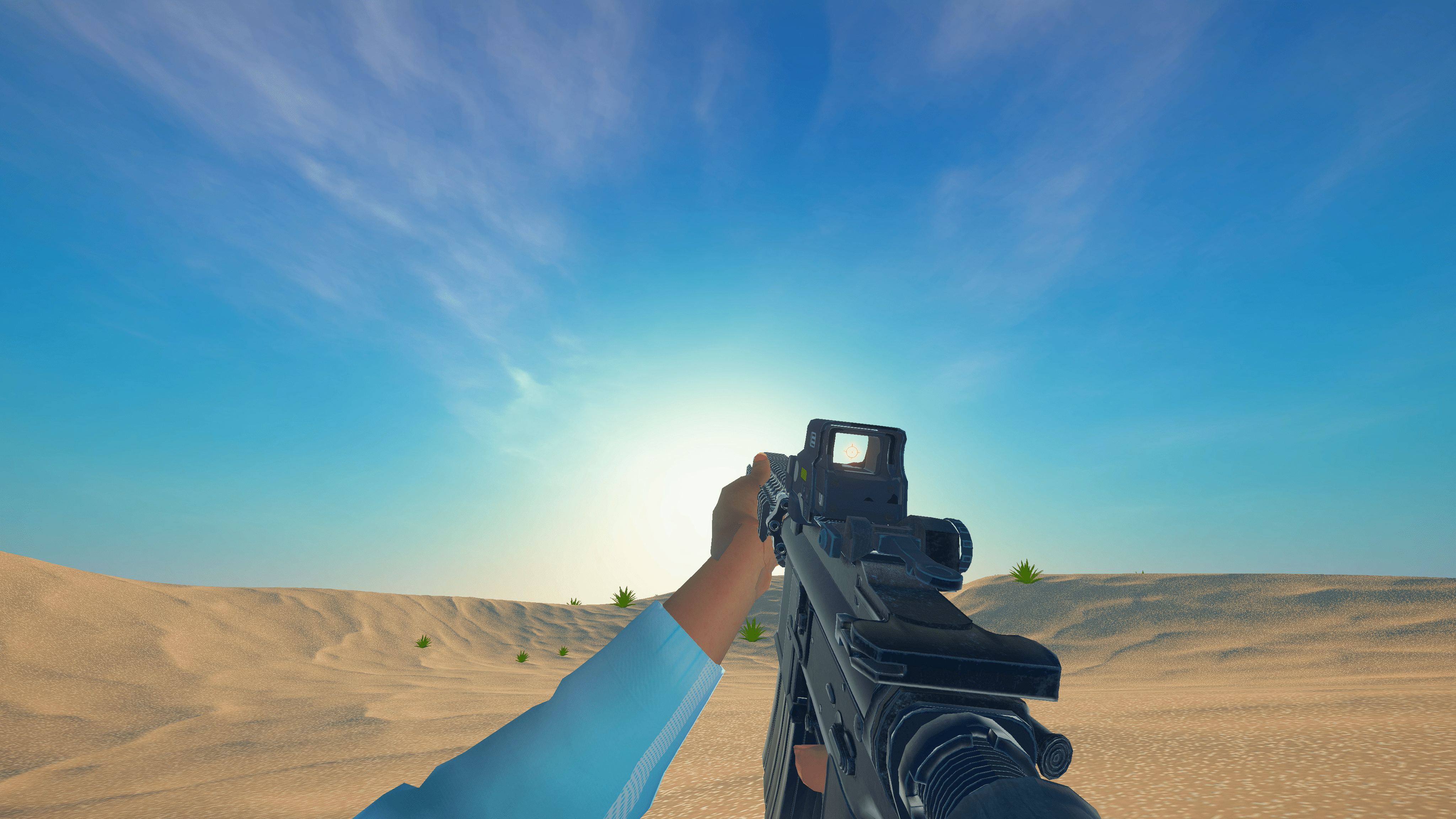

Two years after winning CIRCA PRIZE 2023 with Four Ballads for My Father–Spring, Berlin-based artist Cemile Sahin pushes further her exploration of warfare technologies with ROAD RUNNER, a fifteen-minutes film produced with the £30,000 prize funded by #CIRCAECONOMY. Employing “a mash-up of narrative strategies from film, TV, video games, and social media platforms,” the work fictionalizes drones as instruments of control in a not-so-far future. Premiered by CIRCA and Esther Schipper in Berlin—against a backdrop of rampant privatization of politics, resurgence of widespread militarization, and tech corporations such as Google lifting its longstanding ban on AI-driven weapons and tracking systems—ROAD RUNNER is both seductive and unsettling. While its hyper-stylized aesthetics borrow from entertainment and digital media, the film’s real provocation lies in its subject: a world where violence is gamified and surveillance is total. Ahead of the London presentation of ROAD RUNNER, we spoke with Cemile about the relation in between life and art, the power of fiction and pop language.

[Vittoria de Franchis]: Dear Cemile, in 2023 you won the CIRCA PRIZE with Four Ballads for My Father – Spring, a film that narrates the violence of the Southeast Anatolia Project in Northern Kurdistan. The impact of state terror, nationalism, and ideology are recurring themes in your work. How did your personal story influence your research?

[Cemile Sahin]: I’m Kurdish, and that means I’m intimately aware of national and ideological struggles, not only in Kurdistan but globally. However, I don’t engage with these topics simply because of my nationality; I engage with these topics because they are political issues that you need to intensely research and study. I don’t base my work on my family’s history or personal experiences but approach political topics more broadly, examining how history is perceived and narrated. If you work with art, regardless of the medium, it’s fundamental to engage with themes that are close to life. Focusing on political issues helps me understand what I’m part of and what surrounds me.

[VDF]: This focus on life in art reminds me of one of the sixteen panels surrounding ROAD RUNNER in your recently opened exhibition at Esther Schipper, which featured the quote: “In between art and life, you choose life.”

[CS]: Yes, that’s one of my favorite quotes. I believe art and life should always be interconnected. In my work, I aim to focus on universal, emotional life issues that many people can relate to, using aesthetics to inform. While an art exhibition might not change the world, it can still highlight important topics often overlooked—issues deeply tied to real life.

[VDF]: With the CIRCA PRIZE, you’ve created ROAD RUNNER, which differs from the documentary style of Four Ballads for My Father – Spring, incorporating a hyper-pop and millennial aesthetic. How has your approach to storytelling evolved over the past two years?

[CS]: I definitely see an evolution in my work; the more you create, the more you grow. While the two films differ in form, the themes have remained consistent—issues I’ve been exploring for years. I don’t distinguish one piece from another; each new project helps shape the next. It’s a natural progression. With every work, I dive deeper into these themes, approaching them from different angles because they’re so vast.

I thought about ROAD RUNNER for a long time. I usually start with a theme and fully dedicate myself to the form—how to tell the story and what the narration should be. From the beginning, I wanted to experiment with a different narrative format. I drew a lot of inspiration from sci-fi movies and I felt that style would be an interesting way to tell a story about controlling drones.

[VDF]: You mentioned you never base your work on personal stories. There’s always a certain degree of fictionality in the way you approach narration, and in the narration itself. In ROAD RUNNER, the protagonist tries to free her sister from a virtual reality, a combat video game in which she is captive. We’re increasingly prone to lean on fiction to ‘escape’ or save ourselves from dystopia. What’s your take on this?

[CS]: I like to work with fiction in most of my pieces. It’s a narrative style, a form. What’s fundamental is having a specific language and knowing how to tell a story. I can’t distinguish my practice as an artist from my writing. This is why, in films, text and image always seamlessly intertwine; they flow together and often contrast with the heavy themes I explore, such as killer drones in ROAD RUNNER. The drones in the film are the same ones the Turkish government uses to target Kurds.

I could have made an essay film about drones and their use in the past two years, as they were deployed in wars worldwide. But I feel it’s more powerful to channel the same message through fiction, as its language is more intuitive. In ROAD RUNNER, the virtual reality is where drones send you when they try to hunt you down. The only way to access it independently is through the ‘Cream.’ This was inspired by the CV Dazzle project of 2010, where one could avoid being recognized by surveillance cameras using makeup. So the idea was that through the ‘Cream,’ Bêrîtan, the protagonist, could access the VR undetected and fight through the game, but she eventually keeps losing—the ending is open.

[VDF]: Constant exposure to pop culture language, especially on social media, can numb us to even the most shocking content. Given the dramatic nature of your story, how does this narrative style help it stand out and resonate differently than a more direct, confrontational approach? Is it a tool to draw people into a narrative they might otherwise ignore?

[CS]: In some ways, yes, absolutely. But at the same time, it’s also an aesthetic language that I personally like and have developed over the years. My approach isn’t just about following trends; it’s a mix of my personal style and what I believe best fits the content I’m working with. I’ve always loved hyper-pop, colorful aesthetics. Since art school, my style has remained consistent, evolving naturally over time, rather than being shaped by what’s currently popular. I also grew up surrounded by pop culture. The topics I explore are deeply rooted in real life, and using pop culture elements allows me to bring them into my work in a way that feels both engaging and relevant.

[VDF]: What do you mean by ‘real life’? Do you feel there’s a certain degree of unreality in the internet, video games, or social media?

[CS]: No, these are absolutely part of it. By ‘real life,’ I mean everyday life—the reality that unfolds around us. I’m strongly against the idea of the artist as an isolated genius, surrounded by elites and detached from the real world. I’m the opposite of that. This probably comes from the fact that I don’t come from an art family background. Still, growing up, I felt that films were the closest you could get to real life because they have the power to tell profound stories about it. Films always moved me deeply, and that connection has shaped my personal approach to making art.

[VDF]: In your latest exhibition at Esther Schipper, where you presented ROAD RUNNER, you worked with Artificial Intelligence to create the sixteen panels featuring quotes. How did you collaborate with AI?

[CS]: I fed the AI with a lot of my own work to allow my style to emerge, then intensely edited the images. I don’t use AI just to generate; I’m genuinely interested in it. I love technology and all its nerdy aspects. I enjoy going to tech fairs and exploring the latest innovations. I don’t see new tools as something that will inevitably take over the world and doom humanity. What fascinates me most—and something many people don’t realize—is that before new technology becomes part of everyday life, it’s often tested in war zones. GPS, mobile phones—almost everything we rely on today was first used in military contexts before being introduced to the public, making us completely dependent on them. Ten years ago, there was a lot of discourse around the post-internet era, with debates about ‘humankind vs. machine.’ But I think we’ve moved beyond that—technology is so deeply integrated into our lives now that we can’t even imagine a world without it.

[VDF]: You’ve just published a new book, All Dogs Die, which is also the first one to be translated into English. In the coming months, you’ll present ROAD RUNNER in London for CIRCA and then at other cultural institutions worldwide. What’s coming next?

[CS]: I want to create a series of short films. ROAD RUNNER is already quite long at 15 minutes, but I’d like to make the next ones even shorter and experiment with different narrative styles. Exploring these big topics in a condensed format is an interesting challenge.

Cemile Sahin was born in Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1990. She studied Fine Arts at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London and at the Universität der Künste in Berlin. She lives and works in Berlin.

Her artistic practice operates between film, photography, sculpture, and literature. Freely deploying different media, without privileging one or the other, her work embodies today’s synchronicity of image- and text-based communications. Integrating images into her books and text in her image-world, Sahin moves with extraordinary agility between words and pictures, between still and moving image, between text as form, sign, and symbol. Deliberately elliptical and fragmentary, her work’s narrative strategies draw on an episodic format of narration established by contemporary TV series and internet videos. In her practice, Sahin acknowledges the subjectiveness and codedness of all storytelling, and its instrumentalization by the media. Her works find a giddy rhythm in the knowing use of the dynamics of these processes, sweeping away her spectators to unexpected, and sometimes uncomfortable realizations, among them that the writing of history is, and always has been, determined by constantly shifting perspectives.

Vittoria de Franchis is an independent curator, language researcher and writer operating between London and Berlin. Her practice delves into the intersection of sound, performance, moving image and non-formal educational formats, with a focus on the creation of speculative participatory contexts. Currently, she is part of the curatorial team at CIRCA and the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. For many years, Vittoria has been in the directing team at the Milan-based cultural agency Threes Productions and the art and music festival Terraforma. Amongst her projects are the worldwide series of interdisciplinary happenings gggglllloooossssaaaa (2023 – ongoing), the platform on language research and experimentation Unknown Language (2024 – ongoing) and the residency Nuova Atlantide in Bomarzo, Italy (2020 – 2024). Her writings have been featured in Flash Art, 032C, Spike Art Magazine, Terraforma Journal, Resident Advisor and Zweikommasieben amongst others.