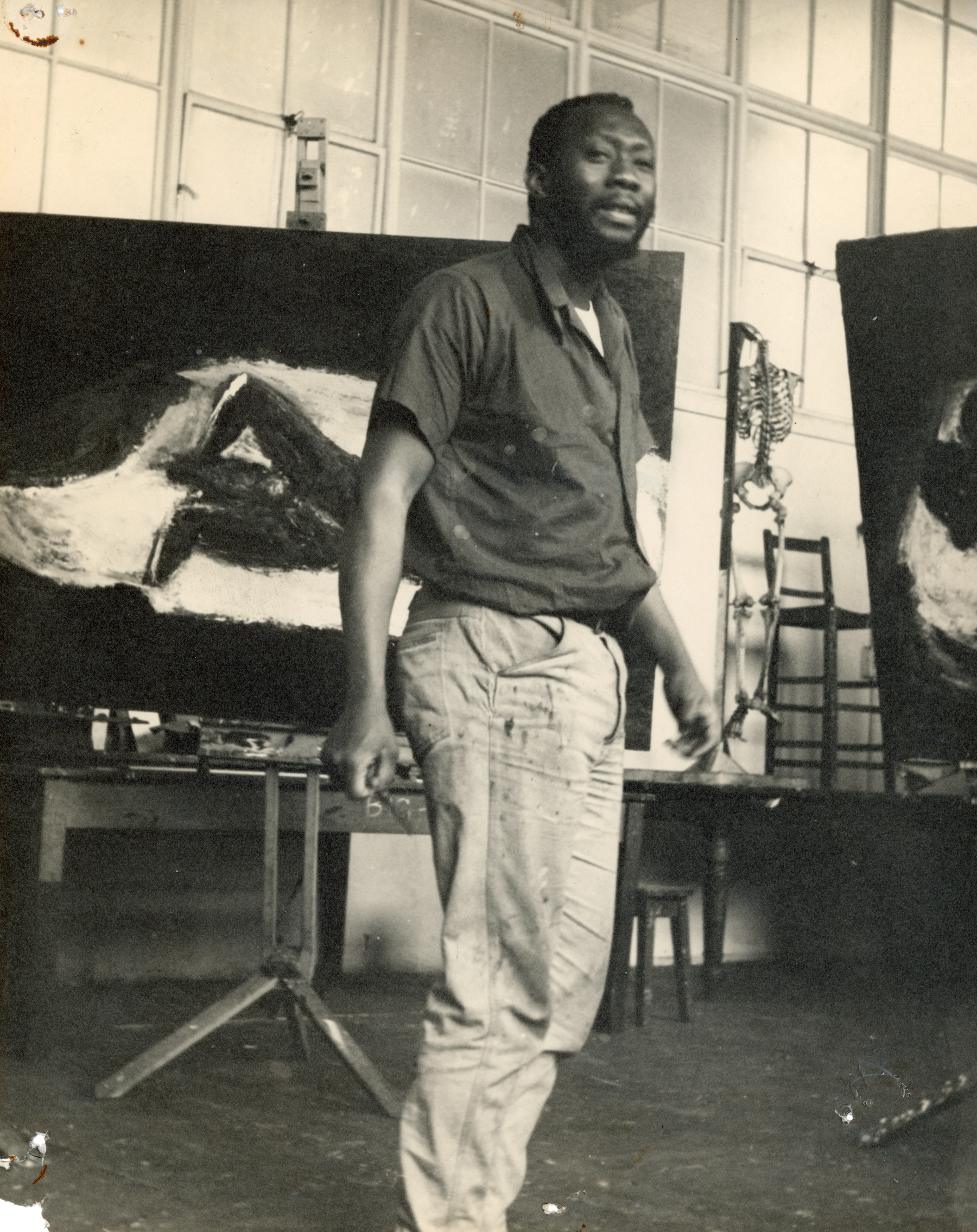

Frank Bowling: A Life in Art

Essay By Farah Nayeri

Frank Bowling is a painter of abstraction: a maker of vast canvases awash with nuances of resplendent colour. These bursts of red, blue, yellow and green look like controlled explosions; they seem purely chromatic, and divorced of any narrative or meaning. Yet look more closely, read the titles, and you will often find, therein, the makings of a story.

Sometimes, that story is a monumental chapter in human history. “Middle Passage” (1970) seems, at first glance, a dazzling fusion of red, yellow and green. The title reveals it to be a homage to the many millions of men and women who were sold into slavery and forced to make the harrowing transatlantic crossing from Africa to the Americas. Faintly stencilled on the canvas are maps of Africa and the Americas and, at the very top, images of Bowling’s sons, Dan and Sacha.

On other occasions, Frank’s painting evokes much more mundane circumstances: the everyday routine of life in the studio, his wanderings around town, his time with friends and family. Titles offer hints: “Benjamin’s Mess” (a reference to his son Ben), “Orange Balloon”, “Girls in the City”, “Great Thames”.

The word ‘abstract,’ in other words, is a fairly imperfect description of the art of Frank Bowling. His paintings are visual diaries: chronicles on canvas of his life and times, and of his metaphysical ruminations. They carry assorted objects from his everyday life – plastic toys, brush handles, car keys and hospital catheters, which are swallowed up by the canvas and seem to live happily ever after on its surface.

These days, Frank’s paintings appear to hark back to his childhood years in the breathtakingly beautiful land of Guyana, which is blessed with 250 miles of Atlantic coastline and an untold number of rivers, streams, creeks and waterfalls. The word Guyana, in fact, means ‘land of many waters.’ Laid out on the floor of his atelier in south London is a vast new painting. Swirls of ocean blue and crepuscular peach converge on the surface of what is a masterpiece in the making.

The painting was produced after Frank’s son returned from a trip to Barbados; there are letters from birthday cakes strewn across the surface. There are also specks of sand from Barbados, seashells — big and small, covered with gold dust — and a piece of crochet that looks like a fish net. Frank seems to be diving back into the waters that enveloped his childhood and adolescence. Gazing at the patches of blue in the work, you feel yourself swimming underwater, past species of sea life.

What, you wonder, was Frank’s initial exposure to art? His mother, Agatha Elizabeth Bowling, had a dressmaking business known as Bowling’s Variety Store on Main Street in New Amsterdam; it was also the family home. Young Frank grew up surrounded by his mother’s sewing machines, the fabrics she used to make saris, and her pinking shears. His job, as a boy, was to cycle from village to village with a basket full of her haberdashery supplies: buttons, ribbons, zips, pins, lace. Yet, for some reason, it never occurred to him to make something of them himself.

His access to art education and museums “wasn’t just limited: it was non-existent,” Frank recalls. “In school, the emphasis was on literature, Shakespeare, and the English poets – that sort of thing. There was no discussion of art.” The only drawing that he remembers ever doing was one of the map of Guyana, an exercise he found truly very difficult. Until his move to England at the age of 19, “I didn’t know that one could be an artist.”

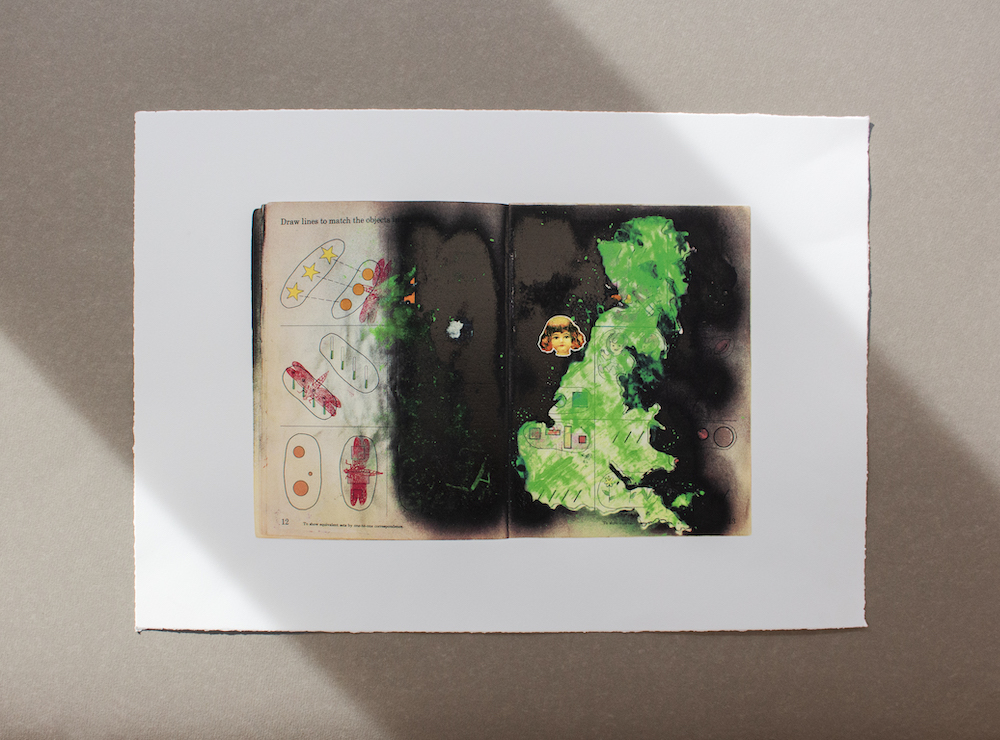

Perhaps because, as a boy, he lacked the most basic art supplies – be it coloured pencils, crayons, or paints – Frank is teaming up with CIRCA to ensure that thousands of schoolchildren in Britain will not. Prints are being made of pages of a Frank Bowling artist book that he made years ago, picturing a map of the British Isles (in reverse). Proceeds of the print’s sale will go towards providing art supplies to schoolchildren across Britain, letting them have what Frank did not.

“Giving kids the materials to work with in schools is vital,” says Frank. Just as vital is encouraging them to make art with objects they come across, in the street or in the park. After all, that’s what Frank has done all his life.

“My studio is full of detritus, found objects, bits and pieces left behind by visitors: I don’t throw anything out. I make use of it,” he explains. “People who want to make creative things will do it anyway. They’ll do it with anything.”

“Putting them on that path is my way of contributing to facilitating that,” he adds. “We’ll be poorer as a society if children don’t have access to arts education.”

Frank Bowling turns 90 this month. He is one of the world’s most remarkable living artists – all the more remarkable because, unlike so many other artists who were active in their 80’s and 90’s, he continues to produce work of the very highest quality. The work, in fact, seems to get better as he goes along.

Frank’s heartfelt desire is for children in Britain today to become artists in their own right. That way, sometime in the distant future, they too can recreate their childhood in a painting on canvas, and top it with the trinkets and souvenirs of a life well lived.

Farah Nayeri is a journalist, author and podcast host based in London. She is the author of Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age. Her CultureBlast podcast features hourlong interviews with personalities from across the world of culture (Emma Thompson, Nile Rodgers, Nan Goldin, Elif Shafak, and Wayne McGregor).