P. ELDRIDGE: THE QUESTION IS THE WORK

A conversation between writer P. Eldridge and artist Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

In this expansive and deeply resonant conversation, artist and technologist Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley reflects on the messy, contradictory, and often emotionally charged foundations of her work. From video game engines to public installations, Brathwaite-Shirley’s practice insists on presence, participation, and refusal.

What emerges here is not a neat artist profile, but a process – a catalogue of questions that resist resolution. Speaking with writer and artist P. Eldridge, Brathwaite-Shirley unpacks how technology fails and is hacked into usefulness, how archiving becomes resistance, and how every artwork begins not with a product but with a conversation.

Together, they ask: What does it mean to make work that demands action? How do we build art that doesn’t just reflect trans life but serves it? And perhaps most importantly: How do we make sure the question survives long enough to be answered fifty years from now?

[P. Eldridge]: Your work often begins with a question: Who gets to enter? Who gets to speak? Who gets to survive? How have your own encounters with systems of power—whether in institutions, online spaces, or everyday life—influenced your decision to use art and technology as tools for intervention?

[Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley]: Gosh, that question makes it sound so tidy – but really, it came out of extremely messy situations. My friends and I were trying to figure out who we were—our identities, how to survive, how to make a living—but also how to reflect each other, how to record what we were going through. We found that we were constantly being erased, or else celebrated for being visually “interesting” or beautiful – but not for what we were doing or how we were thinking.

We ran into problems with institutions that wouldn’t accept us. We had to deal with endless admin issues – clashes with the NHS, the struggle of changing your name at school, things like that.

For me, art became an outlet. It was like keeping a diary – a kind of processing plant. I used it to make sense of what I was going through, how I was going to survive, who I was. All that emotional noise. And then that process—this really personal thing—started being shown. It felt like showing people my diary. But once you learn how to do that for yourself, you realise you can do it for others too.

That’s how my art developed into what it is now. It became a way of processing not just my experiences, but what’s happening to other people too – trying to understand it through their lens, not just mine. But honestly, a lot of it came out of grief. We lost a lot of friends. And growing up, it felt like most of the conversation around trans lives was centred on death. We wanted something else. We were asking: Where are all the trans books? Where’s the art? Where’s the record?

There’s so much more now – but at the time, it felt like there was barely anything. And what did exist often wasn’t accessible. So it became about building a library – creating something that could reflect us back to ourselves.

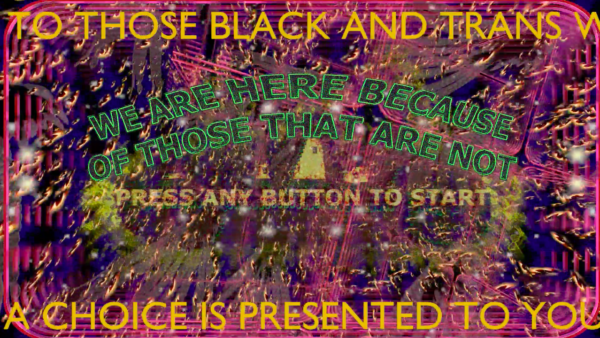

[PE]: That reminds me of digital works like the Black Trans Archive and Get Home Safe, where technology clearly isn’t neutral – it’s part of the very narrative you’re naming. What I find really compelling in your work is how you use code, gaming, and digital spaces to build archives that centre Black trans lives – lives that are so often erased, both physically and in digital records. Did you see these technologies as tools for liberation? As ways of expanding your artistic practice? Or are they also part of the same systems you’re critiquing and challenging?

[DBS]: These tools definitely don’t offer liberation. Most of the time, they weren’t even built to include us – which is exactly why I use such a wide range of technologies. I know, for example, that a game engine or a coding language isn’t going to be able to fully hold or represent even two different types of trans people – not in any meaningful or nuanced way. That’s why I’ve moved through so many platforms and tools.

I think I’ve always used tech from a place of resistance. I know it wasn’t made for me, but I’m going to try and use it anyway, to see what it can express through the language I know and the existence I live. That’s probably why what I make often looks so different – because this kind of technology isn’t typically used to explore the themes I’m interested in. It’s usually used to tell very normative stories, based on very normative assumptions. But when tech is made to encounter something like Black transness—or even just the mindset of Black transness—it suddenly feels like there’s a whole other universe waiting to be uncovered. A new aesthetic, a new vibe, a new kind of world within the tech itself.

That’s how I approach it. I don’t think, Oh great, this new game engine is so easy to use—it’s going to make everything better. More often, I’m drawn to something like a game engine from 1995—maybe it was only ever used for some obscure project where you played a serial killer or something equally grim—and I’ll ask: What would it mean to use this exact same tool to make something useful?

Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t. But I’m interested in pushing tech that was never meant to engage with social issues and seeing what happens when it’s made to confront them head-on.

[PE]: That’s so beautiful. I think that’s exactly how a lot of people experience your work. But there’s also a real tension that exists in that space. You were just describing how a piece of old game design—something that wasn’t originally created with any social impact in mind—can end up being deeply affecting. And I think in a lot of your work, there’s this clear refusal to erase anyone, but also a real emphasis on choice. You offer players the agency to complete the game in multiple ways. To participate means making choices – each one shaping and diverting the outcome. The result is that your games are fun because they resist the idea of a single, fixed narrative or objective.

But at the same time, I think there’s tension there. You’re creating something that could easily be perceived as liberatory—especially in the context of tech—and yet you’re doing so while working within tools and systems that were never designed to hold us. How do you navigate that? When you look back at those old video game designs, you already recognise that tension – that push and pull between intention and possibility, between what the tool was meant for and what you want to do with it. What does it take to make something socially impactful from tools that weren’t built for that? What kind of attention, or intention, is required? What’s that eye, that instinct, that lets you see potential in something so unlikely?

[DBS]: I really feel that I see video games the same way I see books. In books, the way people use language is incredibly varied – that’s the engine that delivers the ideas into your head. With games or interactive experiences, I think the “engine” is more visible. You can really see how it works, how it operates. So I’m interested in how you can use that engine—take the method it’s built on—and observe what it does to the person playing.

I think games often don’t get treated that way. The engine is usually just seen as a tool, not something worthy of creative or critical attention. But if you look at literature, people study how wordplay can shift the entire meaning of a sentence, a paragraph, or even a character’s entire arc. I try to approach each game engine like that – as a medium, not just a tool.

Sometimes that medium was only ever used once, for one game, and I want to see what it could do if I painted a new picture with it. I’m always looking at each engine or system as a method, asking: Could this work? Could this hold something else?

There are a lot of tests – little experiments. And then, when something tracks—when we see a glimmer—we commit. We go all in. That’s when we start embedding a conversation, pushing it into the medium itself.

[PE]: How does that approach translate into your installation work – and into the physical artwork, like painting and drawing? Do you see those practices as connected to the way you think about engines and methods in digital work, or do they function differently for you?

[DBS]: Every work usually starts with a conversation – often one I’ve already had, or one I’ve arranged intentionally with a group of people whose time we pay for, just to talk. Sometimes there’s a set topic, and sometimes there isn’t. Sometimes I just want to hear what’s on their mind. And everything that follows is about trying to archive that conversation.

The basic method is to take that small, intimate moment and expand it – make it feel massive, like it could fill hours of someone’s time. You keep returning to something someone said and build from it: you make images from it, interactions, choices, characters. You might make twenty characters from a single sentence, just trying to capture its essence and nuance from every possible angle. That’s how the work begins to form – it all emerges from trying to serve this moment, to recapture it. But not literally – indirectly, creatively.

For example, someone might say, “I’ve never felt at home anywhere.” That sentence becomes a starting point. From there, you create a character. Then you make a portrait of that character and print it out. You might stick that portrait on a wall. Then maybe you create wallpaper based on the outline of that character’s hand. And then you follow it with another sentence: “Where can my home be?” Suddenly you’ve built an entire environment—both physical and digital—from that moment. A whole world echoing back to a real exchange.

There are rules in how I build these worlds too. For example, when modelling digitally, I only allow myself fifteen minutes to create something. If the model doesn’t work or doesn’t feel right, I can start a new one – but I’m not allowed to edit the old one. So things grow quickly and unpredictably, through accumulation, not refinement.

The drawings, though, are different. They’re much more reactionary. I’ll see something, feel something, or someone will say something—and I’ll draw immediately. It’s a kind of instinctive processing, almost like keeping a diary. If I see, I don’t know, a bomb drop or some other moment of rupture, I’ll think: I need to capture this. The drawing becomes a record of that emotional response, in real time.

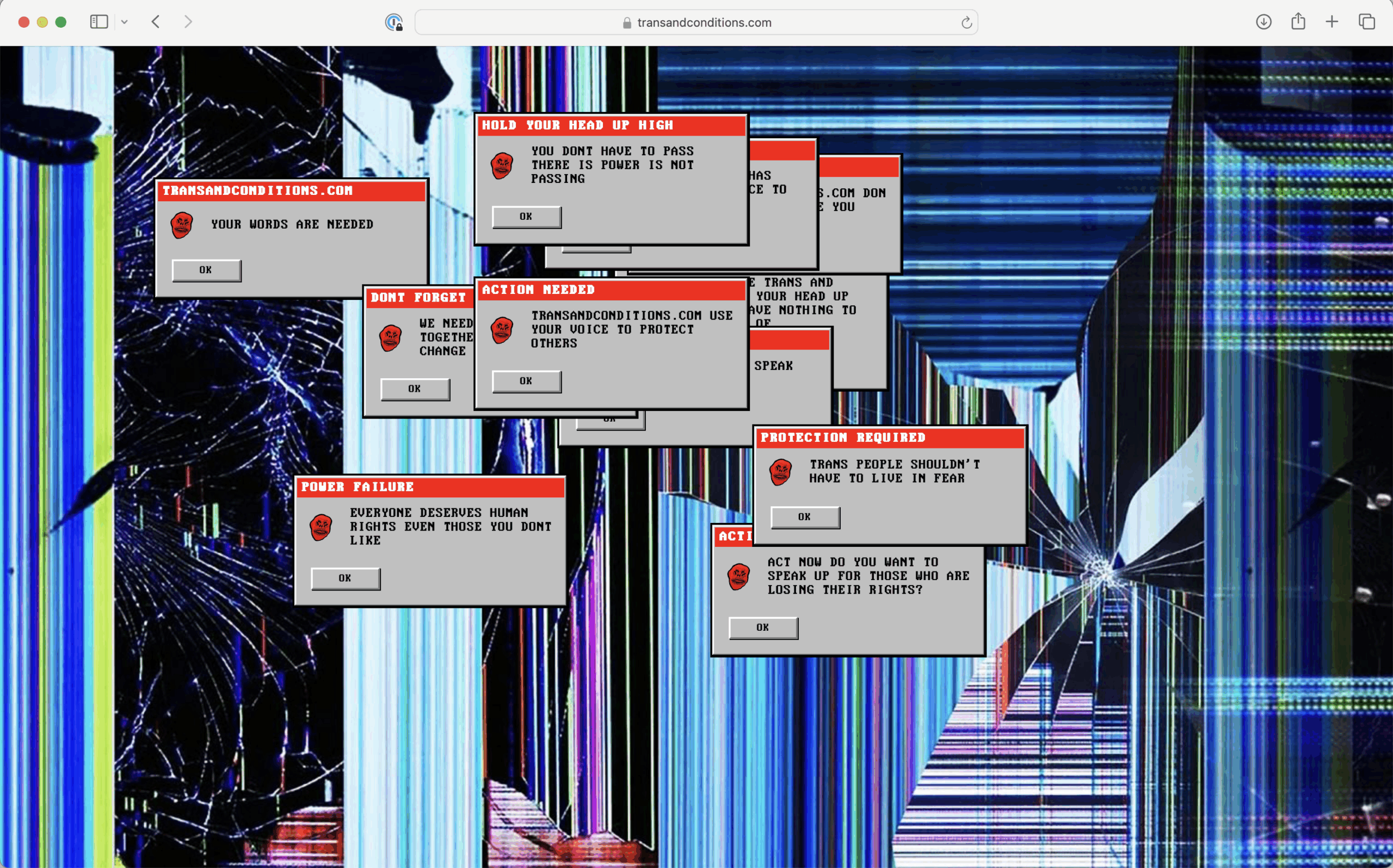

[PE]: With Trans & Conditions, I wanted to ask about the accountability for action that you instigate into the viewers of that see this work, especially in a public space. What responsibilities do you think artists have in ensuring that the people their work meets have the resources to be able to make direct response or a direct action? Trans & Conditions puts the power into someone’s hands by scaffolding this really intelligently designed web face, which feels important on a userface level. They have the responsibility in their hands. Do you think all artists should do that or…?

[DBS]: First of all, I’ll gladly accept all those compliments – thank you so much. [Laughter] I’m not sure all artists should engage in direct action, but what I do believe is this: we’ve had enough “pretty” art. We’ve had enough art where the artist puts time into making the work or doing the research, and the audience simply consumes it—briefly, if they choose to—and then moves on.

What I want is for the audience to have to do the work to experience the art. In fact, I almost feel the work shouldn’t even exist until it’s been touched by the audience – because that’s when it becomes real. That’s when people start thinking about themselves, questioning what they should do, whether they feel confident enough to participate, or whether they don’t want to put in the effort. To me, that is the artwork. That’s the central focus: how much time someone is genuinely willing to give to something they claim to care about – rather than just consuming content that disappears into the void.

I don’t want to create more content. I want the audience to be the feeling, to embody the issues we’re exploring. Right now, it feels like artists are being swallowed by this content machine. Even this interview—yes, even this—is part of it. It’s all wrapped up in noise and nonsense. We’re being packaged as content, and it’s completely useless to us. It doesn’t serve our aims. If anything, it benefits those around us—organisations, institutions—more than it does the actual communities or causes we care about.

The content isn’t there to uplift; it isn’t community-centred. It’s more about the names and networks around the art than the art itself. It’s not supporting the charities or grassroots efforts we talk about. And as an artist, that’s deeply frustrating. Every time we try to put something out there that’s meant to be driven by and for the audience, there’s this enormous system underneath it that has to be mobilised before anyone starts to care.

That’s why I’m moving towards making work that literally doesn’t exist until the audience engages with it. The content machine is consuming everything, and I’m trying to let my work exist for only a limited time – to reclaim some of that space. Because ultimately, the machine benefits those trying to erase the very people I care about. That’s why online protests burn bright and fast – they’re highly visible, but they fade so quickly.

Maybe that’s why I’m so prolific, why I’m constantly working. I want my work to be accessible to everyone – whether through physical spaces, digital spaces, or online platforms. Right now, I’ve even started buying domain names—some of which would have been used for trans porn—because I want us to reclaim that digital space too.

[PE]: That’s so interesting, which domains?

[DBS]: I’m buying domain names like sweatyteagirls.com and transcunt.com, because I know that in five years, this won’t be a conversation people want to turn into content the way they do right now. They might still make content about it – but it will be different. The urgency, the attention, the framing – it will shift.

That’s why I believe that the feeling a person experiences when they interact with the work lasts longer and has more impact. It might finally take the work out of the gallery and into real life—towards an actual person, an actual community—rather than being confined to a gallery space, just seen and then forgotten. The praise often goes to the gallery or the artwork, and then it disappears. I’m not interested in that.

I don’t care if people hate the work. If it makes someone stand up for their trans friend, that’s a massive success. It doesn’t need to serve me in the end. It just needs to do its job.

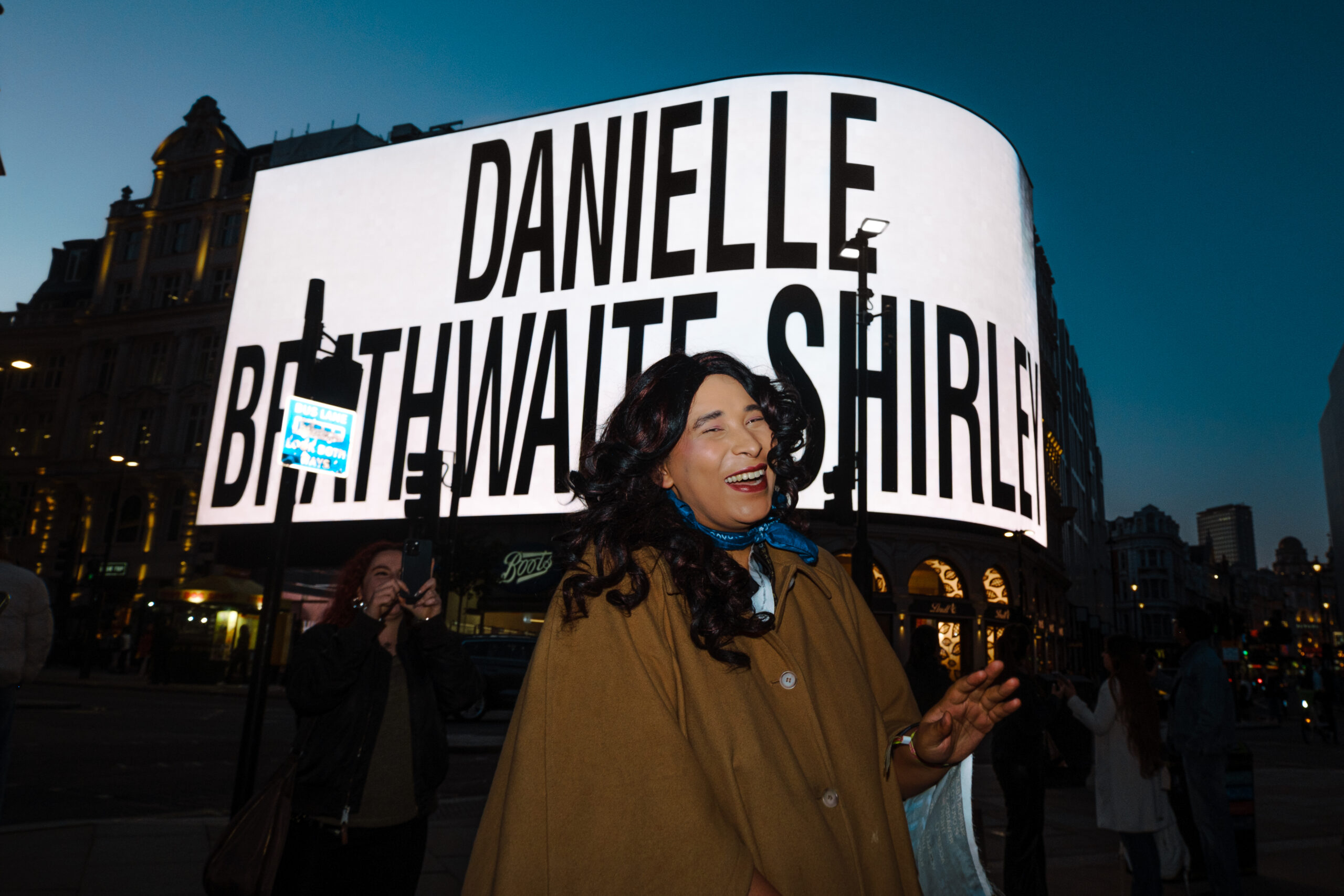

[PE]: Do you think that’s partly because the work itself is reactionary? And I don’t mean that negatively – I mean it in a positive, responsive sense. You were given material resources, the attention of CIRCA, and visibility in such a large public space. I assume there was also a commission fee, which allowed you to create something substantial and reactive in the moment. That enabled people to witness something, to feel something – and, importantly, to care. That responsive feeling we’re talking about – prompting people to act, to do something.

I suppose what I’m really trying to get at—and I haven’t quite formed this as a proper question—is that in writing, there’s a clear narrative structure. You can guide someone through an unfolding emotional state: disdain, pain, pleasure – whatever it may be. Words, when written well, can evoke powerful emotional responses, as you mentioned earlier. But with visual art, particularly in the context we’re discussing now—where there’s a sense of stagnation—I find myself wondering: how do you inject that feeling without relying on documentation? Without the billboard, without the media cycle, without the circuit – how would the work come alive? How would it be activated?

On top of all that, do you think this is how politicians will feel when they receive the Trans & Conditions letters – when they’ve been curated in such a way that they command attention, carry urgency, and feel worthwhile to engage with? There are, of course, many people already actively emailing MPs. But this particular intervention seems to carry a different kind of ferocity – because of the way it disrupts, the way it has been artistically designed, and the way it has been documented.

Perhaps these are just roving thoughts, but I’m genuinely intrigued by how to generate that feeling you described – where the audience has to grapple with the work first, where they have to wade through it and find themselves within it. That point of contact—before it even reaches the institution or the politician—is where something powerful can happen.

[DBS]: Yeah. Oh God, it’s really hard to articulate. I feel like I’m in a very lucky position. Trans & Conditions began because I designed posters for the trans rights protests after the ruling. Then Josef reached out and said, “Hey, let’s do this on a bigger scale.” And honestly, I’m very fortunate to have been given the resources to go bigger. Originally, I was just going to do a large poster campaign. I wanted to make as many posters as possible so people could access them easily. Then I was planning to reach out to charities and create T-shirts and similar things, so that people could donate and support the cause through that.

But then Trans & Conditions came along, which is amazing. But when you go bigger, you start to see the underbelly of media – the way it operates. That brings up other questions: how do we make art that exists within that underbelly? How do we create reactive work that doesn’t sit neatly on a BBC webpage or another surface-level platform, but actually disrupts that? Because when you read an article, you might have an emotional reaction – but rarely does that reaction turn into action. If we could bridge that gap, it would be transformative. It would change how media is used, or at least how it’s consumed.

So for me, working on Trans & Conditions exposed a different layer of this system, and it made me want to place art in that reactive, subversive space. I haven’t quite figured out how to do it yet – but I do know that’s where I want to be. That’s why, personally, I think we need fewer pristine, polished pieces of art…

[PE]: I can’t stop thinking about that phrase—the belly of the beast—and what it means to exist within it, whether as a community or as individuals. I even find myself thinking about video games, or the hero’s journey – the archetypal narrative where the hero must enter the belly of the beast and slay the demon within. That story has always been fuelled by the deep sense that our minds are in our stomachs – that we think through our feelings. I really sense that in what you’re saying – that art should come from that place. From something raw and visceral, sometimes even insidious. That’s where it starts – from this pulsating, unsettled feeling. And the aim is to transmit that to an audience – not to make them comfortable, but to make them feel.

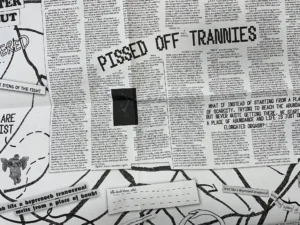

I don’t understand why people insist on making palatable, pretty art. The entire purpose of SISSY ANARCHY—a trans publishing platform I run—to me, is to defend trans stories as they are – whether they’re critically engaged, highly theoretical, cerebral, or disgusting, vile, and putrid. Because let’s be honest, there’s so much anger, so much shame, and so much fear in the trans experience. So why, when we talk about trans art—or look to celebrated examples of contemporary artists who’ve tackled emotional depth and political urgency—why are those works so often pretty, palatable, refined? Why are they always polished, bourgeois, and deemed tasteful? Why are those the qualities the art world deems sexy?

I think the real power we have as trans people making trans art—whether it’s writing, digital intervention, or something else—is that it is grotesque. And that grotesqueness is a mirror to the complexity of trans lives. Trans experiences are often layered with violence, with shame, with those hard, visceral feelings I mentioned before.

I’m constantly, constantly thinking about how to place someone inside that feeling. How to make them sit with it. Of course, that becomes more difficult at different scales. I imagine that’s true for you too – especially with something like the Piccadilly Lights. It introduces a different tone, a different kind of audience.

[DBS]: Yeah, what I love about writing so much is that sometimes an article is published and it completely rocks people. They read it and think, What the fuck? It’s a take they haven’t seen before, one they don’t necessarily like—and it doesn’t have to be right or wrong—but it shifts something. It forces people to reassess, to research differently, to pay attention. There are books that have started wars, or helped to end them. Books that people use as tools – for diplomacy, for understanding, for action.

But art often exists in this strange space. It’s constantly being used as propaganda, to either dehumanise or humanise people. But it’s rarely used as a practical reference point – something that helps you do something. That’s the thing I’m trying to figure out. I don’t know if I’ll get there—and I’ll probably fail many times, which is fine—but I know this: the worst feedback I could get about my work is, “Oh, I liked it. It was nice.” Because if that’s all someone took from it, then it’s failed. That’s useful feedback, but it means it didn’t do what I needed it to do. When I read something like Tech for Dummies, I don’t say, “I liked the book” – I say, “That helped me do X.” When I watch a YouTube tutorial, its value is in the fact that I can now do the thing it taught me.

Art needs to function like that – it needs to intervene. Maybe that’s through media, maybe through news cycles, maybe through structures that allow people to act on it or respond directly. But it definitely can’t just be something I look at, enjoy, and then walk away from. That kind of art is over for me. We’ve done plenty of it – and some of it has been brilliant. There’s a solid canon of trans art now: beautiful, experimental, body-based, popular. And yes, that work mattered – it inserted us into the canon, it made a mark. But we also need another kind of work.

We need the kind of art that galleries don’t want to show. The work that makes institutions uncomfortable. The kind of work that has press teams scrambling, trying to figure out how to handle public reaction. We need art that doesn’t leave people with the feeling of “I enjoyed the show.” We need art that might leave someone thinking: Wait—am I transphobic? Or: I don’t care about trans rights. Or: I’ve just realised I need to do more. Or: I now have the number for a mental health hotline. For me, that kind of emotional and behavioural disruption is far more powerful.

And maybe that’s why I love writing so much – it can do that. You can go from reading a silly Reddit post to seeing a mental health bot pop up with a helpline. That’s the kind of immediacy I want art to have. That’s why I react quickly and take risks in my practice. It’s not perfect, but it’s doing the job. That’s where I’m trying to exist – that’s the space I want to brew in. It’s not polished yet, and maybe it never will be. Honestly, I don’t think I ever want to stick with the same medium twice – especially if it didn’t work. If I ever do something like Trans & Conditions again, it will be very different. I already know I’d consult with a trans-led legal team first. I’d map out the potential pathways so it could be more effective – possibly even feed directly into policy. Ideally, the next iteration would integrate with something like online voting. You know those votes you can do online? I’ve tried and they’re so confusing.

[PE]: Yeah, they’re terrible.

[DBS]: What I want to do is build one, so it’s much simpler, but I need a legal agency to help me understand what the hell the government’s trying to ask me in the first place or anyone. I just feel that we’re in this moment now where I have realised that it can do stuff. Art can literally be a kind of breakthrough way to get people to actually do things. People can interact with it, they can do it, they really can do it, but I’m not sure that’s necessarily what the art world wants to get complicated with. I’m lucky enough that I do, and so I guess that’s the aim – I’m lucky enough to be surrounded by amazing people like yourself that already do that.

[PE]: Danielle, that was so beautiful.

[DBS]: Thank you. But honestly, it’s exactly what I feel your writing does. Do you know what I mean?

I think that’s part of my frustration when I read. Writing can reach us so quickly—it really hits—but at the same time, it’s strange. Because it’s incredible, it’s powerful… but sometimes you have to be 50 pages in. Then suddenly there’s that page. And you’re like, What was that page? It had this one phrase! – and that phrase ends up staying with you, guiding you, shaping how you think for years.

[PE]: I think what people often forget is that a book is a question – and that question can spark action. Whether it’s an essay or a piece of fiction, I’m creating something that should stir you. You know? I’m not interested in all this “we must have an answer” nonsense. I go into commissions making that really clear: I’m not going to deliver something neatly rounded and polished, and I won’t work with an editor who expects that – because I don’t have the answer. I’m just trying to position the question into a reader – and to show how it proliferates when held in tension with many different facets of life. Honestly, all of it feels like a failure anyway. Because the very next day after I’ve finished writing about something—whatever it might be—a new piece of legislation lands, or I change my mind. I allow myself to be contradictory. To believe one thing today, and something else tomorrow, as I hold that question to different realities – both imagined and real.

[DBS]: If it’s a question, how do we ensure that people are trying to answer it 50 years from now?

[PE]: Exactly!

[DBS]: You know what I mean?

[PE]: Yes, this is exactly what I love about Ursula K Le Guin. Everything she wrote was a question, or rather a huge question – one that asked: what’s to come? What if history didn’t begin with violence and bludgeoning tools? What if it wasn’t patriarchal at its core? What if, instead, we centered the women who were creating carrier bags – gathering, planting seeds, bringing beauty home, adorning their habitats with care and intention? That reframing is remarkable to me, because it shifts everything. It asks us to reimagine the foundations.

One of my favourite things about writing is that it creates legible history. I come from a continent shaped by colonial violence – where Indigenous people have been written out of history. And so, for Indigenous communities in so-called Australia, storytelling, writing, narrative – they’re not just tools of reflection, they’re tools of survival. They’re a way of documenting what comes next, of creating a future through story. For me—as a writer—there’s a very clear structure that any piece should revolve around: it has to be a question. I always think, I want what I write in a collection. So that many years down the line, younger trans people—or anymore, more broadly—can say, “These were the questions, the upheavals, that guided our ancestors.”

[DBS]: How do you work around the archiving with your own practice then?

[PE]: I mean, I’ve been so focused on physical intervention – SISSY ANARCHY being a clear example of that. I haven’t really entered the digital space yet, partly because my first passion was always archiving. That’s how I fell in love with radical zines and past publications – because you can be sifting through a bin or a box full of this beautiful, aged material, and there’s this intimacy to it. You can see how it’s been handled, folded, annotated – how people have engaged with it. You can feel it in your hands, in your presence. SISSY ANARCHY was very much a response to that.

With printed material, when you’re the curator, you hold this editorial power: the ability to omit or include. With SISSY ANARCHY, the ethos is always to include – never to omit. So when I created it, it was originally just to be inserted into an archive. That was the purpose. But then people started encountering it in archives and asking, “How can I access this outside the archive?” That’s when I realised: Okay, this needs to be something people can access without having to physically go to an archive – something that exists beyond geographic or institutional boundaries.

I’m obsessed with creating a paper trail. Especially because I love the way it burrows into unexpected, feral places. I once had a 16-year-old come to a book fair with their parents. Their parents were down the hall, and they quickly came over and bought a copy from me. I asked, “Do you need a paper bag? Something to conceal it?” And they said, “I’ll be fine. I’m going to stuff it down my pants, and when I get home, I’ll keep it in a shoebox under my bed.” I thought: That’s exactly where I want it to be. Because I know it’s serving that kid.

SISSY ANARCHY becomes this living, throbbing representation of who they are – something they can return to, something that reflects them, no matter what town they’re in. They’ll sit in the car with their family, that zine pressed up against their body, and they’ll feel the impact of it. When they get home and open it, that’s where the power is. That’s putting words into action.

It’s not just about putting something online to quietly wither in a digital archive. I’m interested now in how to translate that feeling – how to create something online that still carries that intimacy, that urgency, that sense of being for someone in a specific, visceral way.

[DBS]: I love that story, it’s so amazing. It’s really an intro for a game. [Laughter] Let’s make a game!

[PE]: [Laughter] I’m telling you, definitely!

[DBS]: [Laughter] Yes!

P. Eldridge is a curator, writer, and cultural agitator working between London and so-called Australia. She is the founding editor of SISSY ANARCHY – most recently featured at the sixtieth Venice Art Biennale – ‘SISSY’ columnist for Gay Times, director of Worms World, and co-founder of The Compost Library; platforms dedicated to unruly voices, queer resistance, and experimental writing. Her work has appeared in Flash Art, Studio Magazine, CIRCA, and more; and she has interviewed artists and writers such as Judy Chicago, Juliana Huxtable, Shon Faye, Cortisa Star, and Torrey Peters. She has edited writing by Chris Kraus, Anne Rower, Estelle Hoy, and Octavia Bright, and her practice has been featured in DAZED, Service95, AnOther, and at Tate Modern, to name a few. Her practice is a soft weapon, a sharp tenderness carving space for queer embodiment, refusal, and new ways of living.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley (b. 1995, London) is a Berlin/London-based artist. They received an BA from the Slade School of Fine Art, London in 2019. Brathwaite-Shirley works predominantly in animation, sound, performance, and video game development. Their practice focuses on intertwining lived experience with fiction to imaginatively retell the stories of Black Trans people. Danielle’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions and performances at institutions such as Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona (2024), LAS, Burghein berlin (2024), ,Studio Voltaire (2024), SCAD, Savanna (2023) Artnight Dundee (2023) Villa Arson, Nice (2023) Fact, Liverpool (2022) David Kordansky, LA (2022) Project Arts Centre, Ireland (2022); Skänes konstförening, Malmö, Sweden (2022); Arebyte Gallery, London (2021); QUAD, Derby, England (2021); Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo (2021); Focal Point Gallery, London (2020); Science Gallery, London (2020); and MU Hybrid Art House, London (2020). Their work has been included in group exhibitions at institutions such as Julia Stoschek Foundation, Berlin (2022); Münchner Kammerspiele, Munich (2019); Les Urbaines, Lausanne (2019); and Barbican, London (2018).