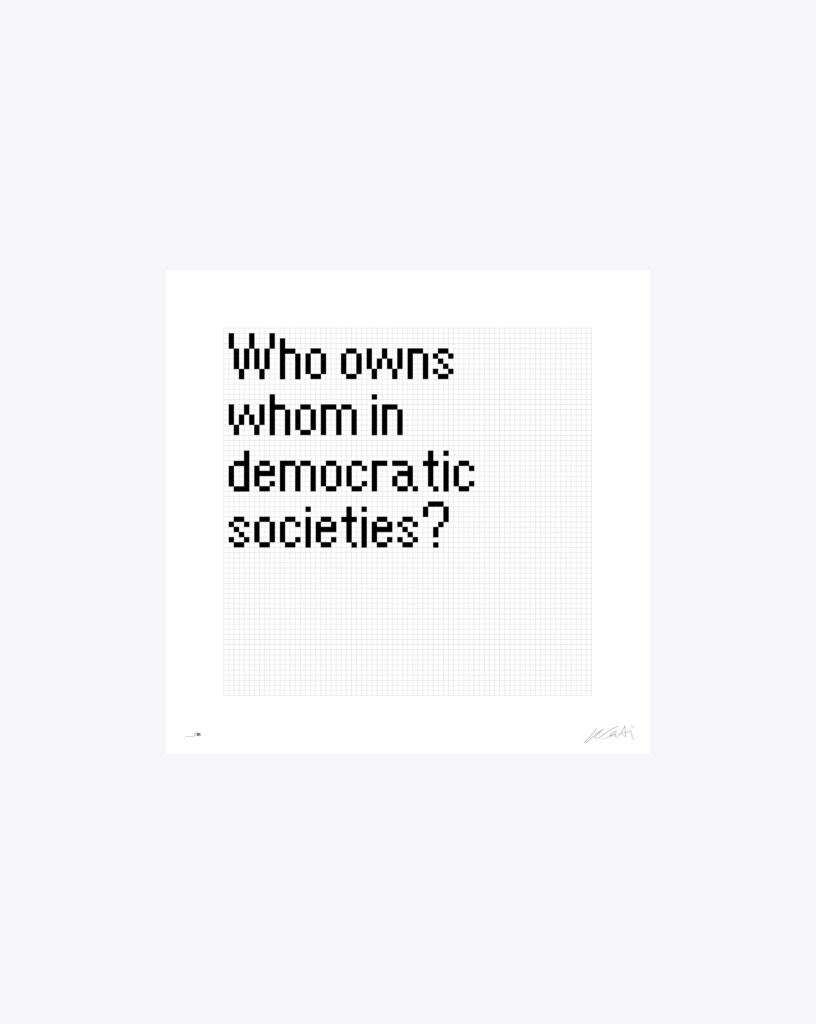

Ai vs AI: Question 28/81

Who owns whom in democratic societies?

Ai Weiwei: In ostensibly democratic societies, the conventional belief is that they belong to the public. Yet, the stark reality of contemporary society reveals that true ownership lies within the realm of capital. Capital, dispersed across various corporate entities, ultimately governs these purportedly democratic societies.

ChatGPT (AI), January 2024: In democratic societies, individuals collectively own the power to influence governance through the electoral process. The government, ideally, is accountable to the people.

ChatGPT (AI), January 2025: In democratic societies, the ideal notion is that citizens own the government, or more specifically, they have the power to govern themselves through their participation in the political process. Democracy is founded on the principle of popular sovereignty, meaning that political authority comes from the people. Citizens elect representatives, form political parties, and have a say in the creation of laws and policies that govern their lives.

However, the relationship between ownership and power is complex, and in practice, it often involves a nuanced interaction between different social, political, and economic forces. Below are some important dimensions of “ownership” in a democratic society:

- Citizens’ Ownership of the Government (Political Power):

Citizens’ right to vote is the most direct form of ownership. In a democracy, people have the ability to choose their leaders, whether through direct elections or representative democracy.

Elected officials are accountable to the people, who can remove them from office through voting, protests, or other democratic processes. This is the foundation of democratic legitimacy.

Political rights—like free speech, assembly, and protest—allow citizens to influence the direction of the government and hold their leaders accountable. - The State’s Role as a Facilitator of Public Interests:

In democracies, the state—through institutions like legislatures, courts, and executive branches—serves as a mechanism to implement the will of the people. The government is supposed to serve public interests and protect citizens’ rights, liberties, and security.However, while the state may be accountable to the people, it also often reflects the interests of powerful groups like corporations, elites, or special interest groups. This can sometimes skew the relationship, creating a dynamic where certain groups hold more influence than others. - Economic Ownership: Corporations and Wealth:

While citizens may have political ownership in a democracy, the economic structure often reveals a different kind of “ownership.” Wealthy individuals and corporations can exert significant control over policy through lobbying, campaign donations, and economic influence.Corporations: In many democratic societies, large corporations have significant sway over the economy, and by extension, political decisions. This influence can lead to an imbalance in how policies are made, with the interests of the wealthy sometimes taking precedence over the needs of the broader population.

Wealth distribution: The concentration of wealth in the hands of a few people or entities can create power imbalances. Wealthy individuals or corporations may indirectly shape policies to maintain their economic interests. - Media and Information Ownership:

Another critical aspect is the ownership of media and information. In many democracies, a small number of entities or individuals control a large portion of the media, influencing public opinion, political narratives, and the flow of information.Media ownership can play a significant role in shaping public perception, which in turn affects how citizens make decisions, vote, and engage with their governments.

Citizens ideally “own” the right to receive truthful and diverse information, but media concentration can limit access to a wide range of viewpoints. - Social Movements and Civil Society:

Beyond elections and political institutions, civil society—which includes advocacy groups, nonprofits, unions, and grassroots movements—also plays a key role in holding governments accountable and advancing causes.Social movements and activists often drive changes in laws and policy, influencing the political system and raising awareness of issues that might otherwise be overlooked. These movements can sometimes counterbalance or challenge government power and corporate influence.

Global Influence:

In an increasingly globalized world, democratic nations often find themselves influenced by international organizations, foreign governments, and global economic forces. This can lead to complex dynamics where political sovereignty may be affected by global agreements, treaties, or economic dependencies.

The Paradox of Ownership in Democratic Societies:

Ideal vs. Reality: The ideal of democracy is that the people own the government and control their political destiny, but in practice, other actors—such as economic elites, corporations, or even foreign powers—may exert disproportionate influence, potentially undermining the principle of popular sovereignty.

Public vs. Private Interests: There’s an ongoing tension between public interests (the welfare of the many) and private interests (the wealth and power of the few). In many democracies, the balance between these two forces shapes how effective and representative the democratic system is.

Conclusion

In democratic societies, citizens ideally “own” the government through their participation and voting rights, but in reality, political power can often be influenced by other forces, like economic elites, corporations, and media. The balance between democratic principles and private influence is a central challenge, and many democracies struggle with ensuring that the government remains responsive to the people, rather than to powerful interests.

Ultimately, democracy works best when people stay engaged, demand accountability from their leaders, and work to address the inequalities that may skew the balance of power.

Would you like to discuss any specific examples of this dynamic in action?

DeepSeek (AI), January 2025:In democratic societies, the concept of “ownership” is not typically applied to people, as modern democracies are built on principles of equality, individual rights, and freedom. However, the question of “who owns whom” can be interpreted in terms of power dynamics, influence, and control within society. Here’s an analysis of how power and influence operate in democratic systems:

- The People Own the Government:

– In a democracy, sovereignty lies with the people. Citizens elect representatives to govern on their behalf, and the government derives its authority from the consent of the governed.

– This is often expressed through the principle of popular sovereignty, where the people are the ultimate source of political power. - Influence of Wealth and Corporations:

– While democracies aim for equality, economic disparities can lead to unequal influence. Wealthy individuals, corporations, and special interest groups may exert significant influence over political processes through lobbying, campaign donations, and media control.

– This has led to concerns about oligarchic tendencies, where a small group of powerful entities effectively “owns” or controls political outcomes. - Media and Information:

– Media organizations play a critical role in shaping public opinion and political discourse. In some cases, media ownership is concentrated in the hands of a few powerful entities, which can influence what information is disseminated and how it is framed.

– This raises questions about whether the public truly “owns” its own opinions or if they are shaped by those who control information. - Labor and Economic Relationships:

– In capitalist democracies, employers “own” the labor of their employees in the sense that they pay for their time and skills. However, labor laws and workers’ rights aim to balance this relationship and protect employees from exploitation.

– The rise of gig economies and precarious work has sparked debates about whether workers are being treated as disposable or “owned” by corporations. - Technology and Data:

– In the digital age, technology companies collect vast amounts of data on individuals, leading to concerns about who “owns” personal information. While individuals generate the data, corporations often control and monetize it.

– This has sparked discussions about data privacy, ownership, and the need for regulation. - Social and Cultural Ownership:

– Democracies strive to ensure that no single group “owns” or dominates cultural or social narratives. However, historical inequalities (e.g., racism, sexism, classism) can create systems where certain groups hold disproportionate power over others.

– Movements for social justice aim to address these imbalances and promote a more equitable distribution of power. - The Role of Institutions:

– Democratic institutions (e.g., courts, legislatures, and regulatory bodies) are designed to prevent any single entity from gaining too much power. Checks and balances are in place to ensure that no one “owns” the system entirely.

– However, the effectiveness of these institutions depends on their independence, transparency, and accountability.

Conclusion

In democratic societies, the ideal is that no one “owns” anyone else, and power is distributed among the people. However, in practice, economic, social, and political inequalities can create power imbalances that challenge this ideal. The ongoing struggle for democracy involves ensuring that power remains in the hands of the many rather than the few, and that institutions are designed to protect individual freedoms and promote equity. Ultimately, the question of “who owns whom” highlights the importance of vigilance, participation, and reform in maintaining a truly democratic society.

Google Gemini (AI), June 2025: In democratic societies, the fundamental principle is that the people own the power, and the government serves the people. This is often articulated through the concept of popular sovereignty, which means that the authority of the government is derived from the consent of the governed.

Here’s a breakdown of this relationship:

– Citizens as the Sovereign: In a democracy, the ultimate power rests with the citizens. They are considered the “owners” of the state’s power, not the other way around. This is in stark contrast to authoritarian or totalitarian regimes where the state or a ruling entity “owns” its citizens.

– Government as the Servant: The government in a democratic society is a temporary and accountable body elected by the citizens to manage public affairs on their behalf. It is seen as a tool or an instrument for implementing the will of the people, not a master.

– Consent of the Governed: The legitimacy of a democratic government stems from the consent of its citizens, typically expressed through free and fair elections. If the people withdraw their consent (e.g., by voting out a government, through peaceful protest, or in extreme cases, revolution), the government’s authority is undermined.

– Rights and Freedoms: Democratic societies emphasize individual rights and freedoms, which are inherent to the citizens and not granted by the government. The government’s role is to protect these rights, not to infringe upon them.

– Accountability: Governments in democracies are accountable to their citizens. This means they can be held responsible for their actions through various mechanisms like elections, free press, independent judiciary, and civil society oversight. If a government fails to represent the people’s interests or acts against them, it can be removed from power.

– “Of the people, by the people, for the people”: Abraham Lincoln’s famous phrase encapsulates this idea perfectly. The government is:

– Of the people: Composed of individuals from the populace.

– By the people: Chosen and empowered by the citizens.

– For the people: Exists to serve the interests and well-being of the citizens.

In essence, the relationship is one of delegated authority. Citizens delegate a portion of their collective power to the government to ensure order, provide public services, and protect rights, but they retain ultimate sovereignty and the power to reclaim or redirect that authority.

To coincide with the exhibition, 81 Questions – a series of 81 hand-signed and embossed screen prints featuring the 81 questions posed by Ai Weiwei – are available exclusively on CIRCA.ART for £500+VAT.

“Each Lego brick pixel represents a person”, says Ai Weiwei, who incorporates the plastic construction toy – a readymade material incorporated into many of his most recent works – into his print design for the first time. The black egalitarian pixel font and embossed baseplate combine technology with artisanal craft to create this thought-provoking and playful reflection on today’s world. Each print in the series of 81 Questions is hand-signed and numbered by the artist in editions of 81.