Frank Bowling: Frankie

Written by Somaya Critchlow

‘And my special geography too; the world map made for my own use, not tinted with the arbitrary colours of scholars, but with the geometry of my spilled blood’ – Aime Cesaire

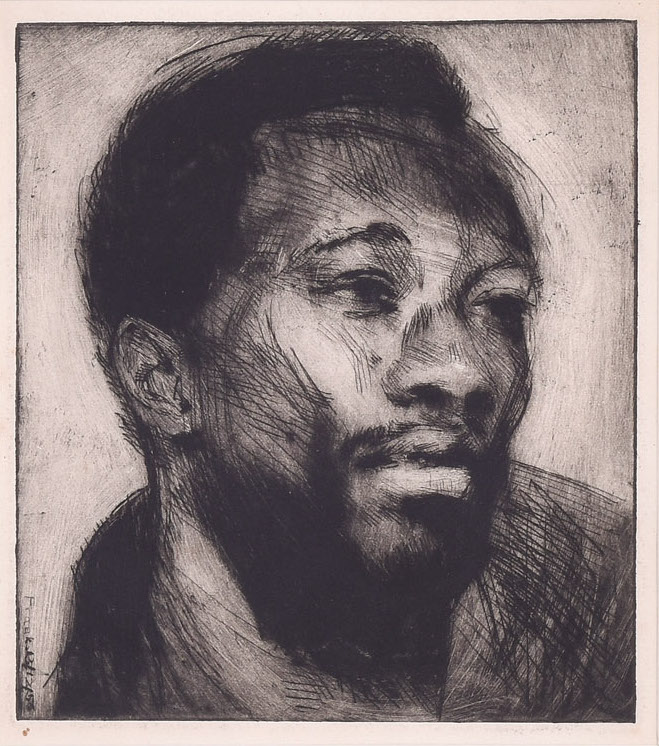

I first met Frank Bowling through the lithograph that hung in my Grandparent’s front room. A beautiful black and white portrait of a black man by my Grandfather Keith Critchlow, reminiscent of Rembrandt and other Old Master prints and drawings found during visits to The National Gallery and British Museum whilst studying.

I can’t imagine, at the time, that I was conscious of its meaning – that of being a black man – but on reflection, I see how obviously, yet unknowingly, significant it was to me. I was 18 and studying at City & Guilds of London Art School when I properly met Frank Bowling, putting a real-life presence to the face in my Grandfather’s portrait, and from which I began to form a deeper worldly understanding of who the man, lovingly referred to as ‘Frankie’ by my Grandparents, was as both an artist and friend.

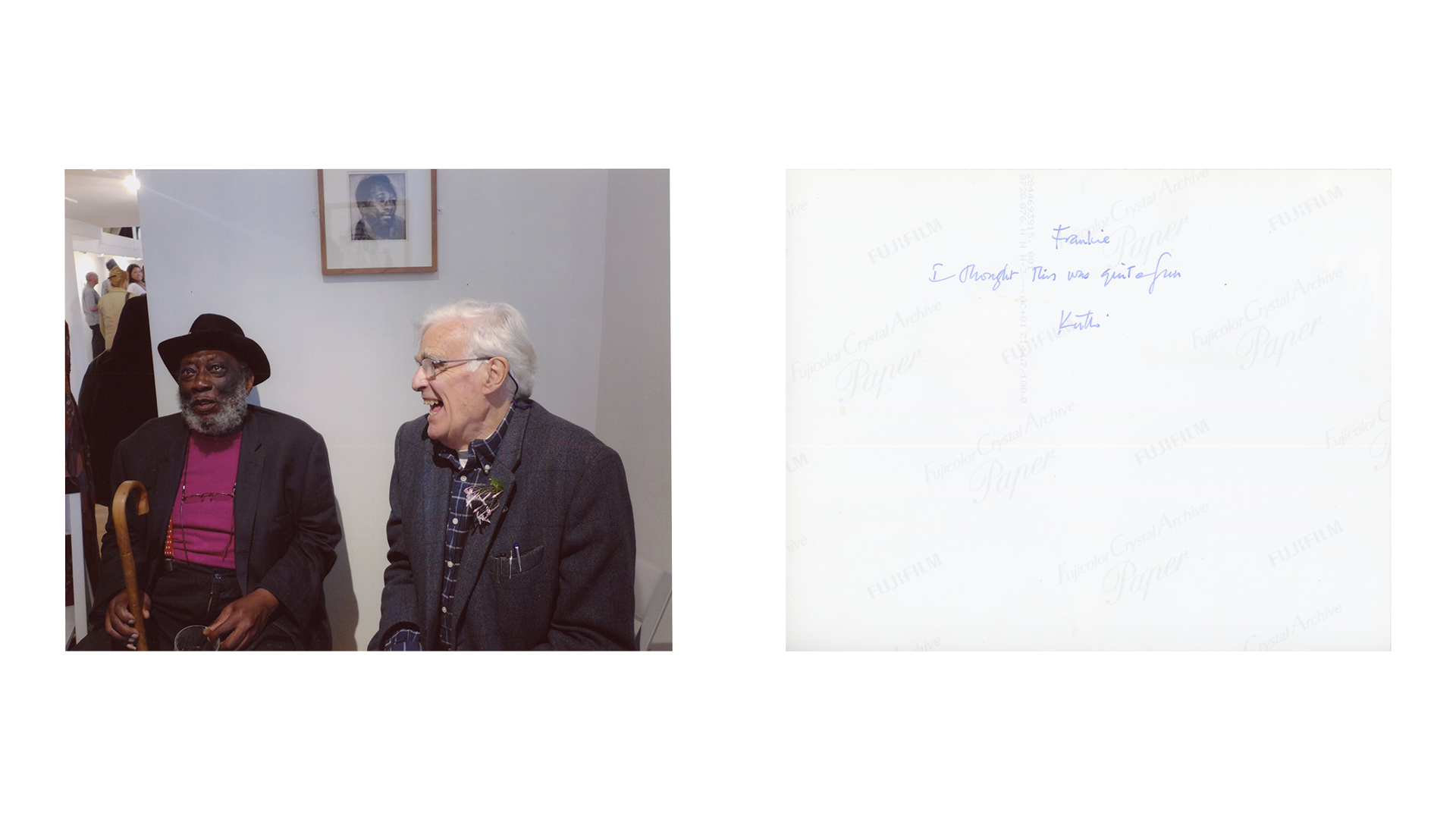

The first time I properly saw Frank Bowling’s work was in the summer of 2013, at the Cello Factory exhibition Frank Bowling and his Invited Artists, which also included the work of my Grandfather, my Grandmother Gail Critchlow and my Mother, Amelia Critchlow. My memories of this exhibition, as a family affair, seem appropriate to how I have known Frank as both person and artist through many connective points in my life: the same geometry that connected Frank and Keith both professionally and metaphysically through their lifelong friendship since first meeting in the RAF in the 1950’s. Frank has recalled that my Grandfather Keith was ‘his first ever art teacher’ and that Keith and our family introduced him to the British art galleries and collections of Western Art. This is very much my own experience with my Grandfather, and I love to imagine Keith and Frank walking through The National Gallery, the Victoria & Albert Museum and British Museum in the 1950s and ’60s, discussing everything they saw: just as I myself did with Keith from my childhood to the last exhibition we saw together, Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art at The National Gallery in 2016.

My first ‘seeing’ of Frank’s artwork is through this deeply personal lens. The most profound experience I have of seeing Frank’s work was upon visiting his expansive retrospective at Tate Britain in the summer of 2019. The exhibition was so full: bursting with a vastness in range of approaches, techniques and ambitions. The crisscrossing over decades in his life. I was overwhelmed to see how much Frank has contributed to British art and has, and continues to this day, to explore his artistic practice.

Frank Bowling’s Map (1967-1971) and Poured paintings (1973—1978) have always held great significance for me as they are poetic in their physicality, abstractions that contain deeply personal memories and history. It is who he is and what he does, in his existence and his pursuit of painting, that means so much to me.

Frank rejected the idea that artists who are black should have to make overtly political protest artwork. The personal history in Frank’s work permeates without it being necessary to explicitly state or relate the outcomes to over-politicised meanings of Blackness. This idea of having to make work that is overtly political is something that I often contemplate myself whilst considering what informs my desire to paint and the shapes the subjects of my paintings take on.

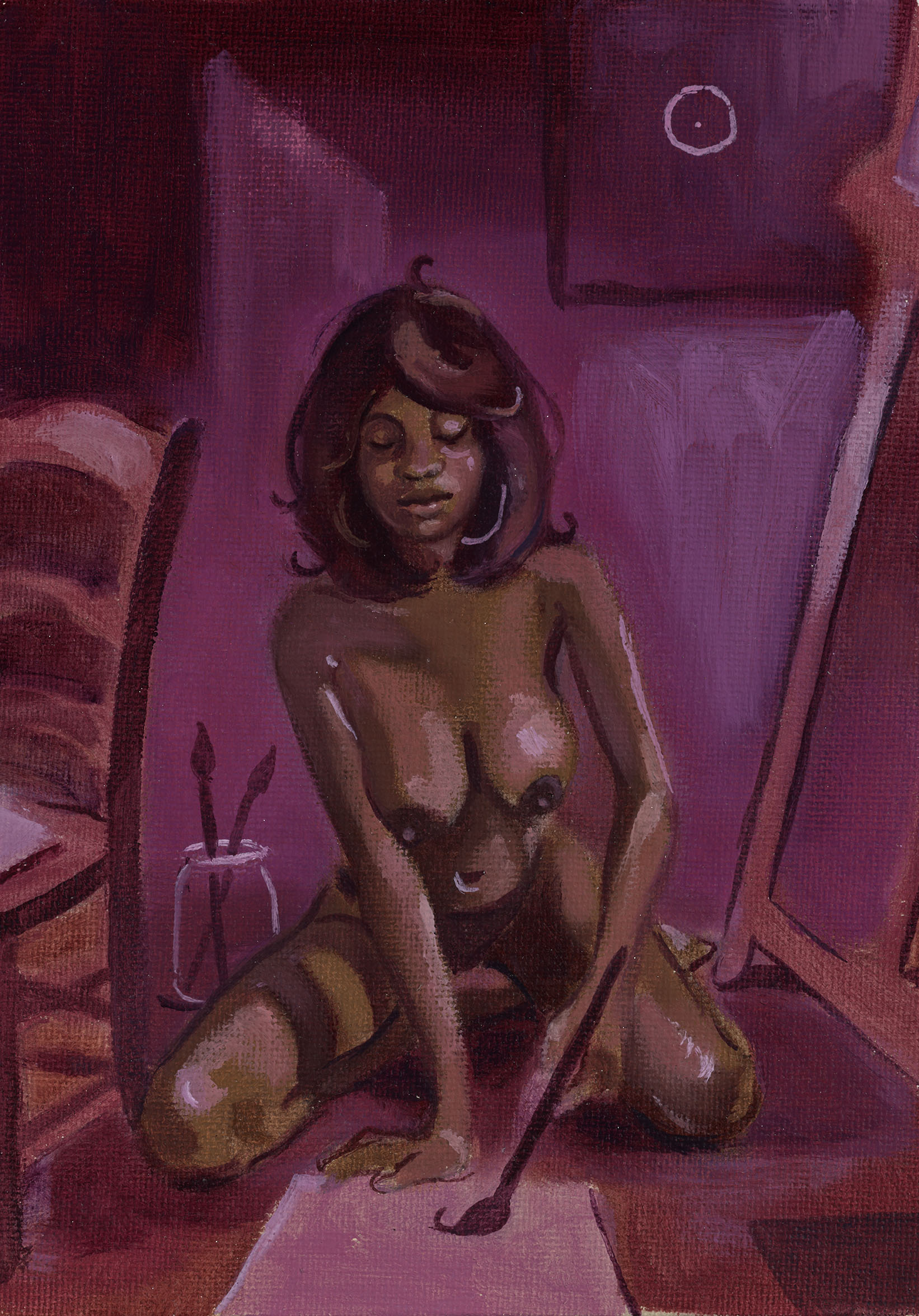

I know of Frank’s love for Titian, Rembrandt, Gainsborough, Constable and Turner: all part of his pantheon and all great loves of my own. When I look at Frank Bowling’s early figurative paintings, I am fascinated by those such as The Abortion (1962), Birthday I (1960) and Self-portrait (1959). I see the hand of an eye that adores paint, moving across the surface seeking out shape and form, and his connection to the painterly surface in the works of the masters of the Renaissance and 18th and 19th-century Western painting. The tumultuous and somewhat unsettling subject matter of these paintings by Frank leads me to recall Titian’s ‘poesie’: a sense of the implied or perceived mythology that can imbue a subject’s existence in Frank’s work, just as in Titian’s literal depictions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Frank’s work has transformed over time, a metamorphosis of his being and techniques that have expanded to explore new potential from paint as a material. Though there is lightness in his work, most recently in his landscapes, which are iridescent and colourful, they bleed across the canvas surface. After a lifetime of working as a painter, perhaps the landscape is a metaphor that contains all his thoughts and ideas as they ebb and flow throughout one’s life and existence.

I arrived at the work of Frank Bowling through personal connections to him in my childhood, yet I also arrive at his work as I have grown as a black woman who has had to learn to understand the world around her and what it is to view and be viewed. Frank occupies a very symbolic position in my life, beginning as a familiar face in my Grandparents’ home to a figure whose work is embedded in the British history of art that I love so much.

Somaya Critchlow (b. 1993, London, United Kingdom) is an artist living and working in London. Critchlow received a BA from the University of Brighton, United Kingdom, in 2016, before joining The Royal Drawing School, London, where she completed a Postgraduate Diploma in 2017. Recent solo exhibitions include Afternoon’s Darkness, Maximillian William, London (2022); Blow-Up, Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zürich, Switzerland (2021); Underneath a Bebop Moon, Maximillian William, London (2020); and Sincere for Synonym, Fortnight Institute, New York, NY (2019). Her work has been included in numerous group exhibitions, including The Story of Art as it’s Still Being Written, Victoria Miro, London (2022); Women Painting Women, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, TX (2022); Drawing Attention: Emerging British Artists, British Museum, London (2022); Fire Figure Fantasy, ICA Miami, FL (2022); among others. Critchlow’s work is included in the permanent collections of the Arts Council Collection, London; British Museum, London; Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, United Kingdom; Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art, Norwich, United Kingdom; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Baltimore Museum of Art, MD; LACMA, Los Angeles, CA; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA; Columbus Museum of Art, OH; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA; RISD Museum, Providence, RI; Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA; and ICA Miami, FL.